Cursus

Besides my partner and me, there are four people who hold a key to our house: our best friends, and my parents-in-law. They have a set of keys each, to do things like water the plants or borrow extra chairs for parties while we’re on holiday. I didn’t give any of my neighbours a key because I don’t know them that well, and I don’t see any reason they should need to access the house while I’m away. I don’t leave a key under a plant pot for anyone to use, and I certainly don’t leave the door open when I leave either. That would be a disaster waiting to happen, right?

Well, the same concept applies in cybersecurity: only give people and systems the access they actually need to do their job, nothing more. It’s called the Principle of Least Privilege, or PoLP for short. No default admin rights, no “just in case” superuser privileges, and definitely no all-access passes floating around in forgotten test accounts. The more access people have, the more there is to lose if something goes wrong!

In this article, we’ll walk through how PoLP works behind the scenes, and why it’s one of the most effective ways to reduce risk. You don’t need a cybersecurity background to follow this article. In fact, the goal is to make the concept accessible enough that anyone working on a tech project can implement it and make their application a little more secure!

What Is the Principle of Least Privilege?

The Principle of Least Privilege (PoLP) is sometimes also called the Principle of Minimal Privilege (PoMP) or Least Authority (PoLA). It is exactly what it sounds like: only give people or systems the least amount of access they need to do their job. Not the most they could need, not what’s easiest to set up but just what they actually need, and nothing more.

Importantly, this doesn’t just apply to people. PoLP is for everyone and everything: users, services, apps, virtual machines, APIs, and even background processes. If it can log in or access a resource, it should be treated like a potential risk and only allowed to do what’s necessary.

Following this principle forces you to be intentional: Who really needs access to what? For how long? And what happens if those keys fall into the wrong hands?

How the Principle of Least Privilege Works

Okay, so we have seen that PoLP is about limiting access to the bare minimum. But in practice, that doesn't just mean saying "no" a lot. It means designing systems and processes that grant access intentionally, temporarily, and with guardrails. There are several strategies to do that:

Role-based access

Instead of granting permissions to individual users ad hoc, you assign roles, like “developer,” “analyst,” or “finance”, each with a predefined set of access rules. It’s cleaner, easier to manage, and avoids the mess of one-off exceptions piling up over time.

Time-limited or Just-in-Time (JIT) access

Sometimes people really do need elevated permissions, but only for a specific task or window of time. With JIT access, users can request temporary privilege elevation, usually with a clear expiration time.

Privilege bracketing

A more technical flavor of JIT: a script or user briefly gets elevated rights for one operation, then drops back down immediately after. This is pretty common in DevOps workflows.

Modern access models like Zero Trust

PoLP also plays a huge role in Zero Trust Network Access (ZTNA). In a Zero Trust model, no user or device is trusted by default: everyone must prove who they are and justify what they want to access, every time. Least privilege is in there right from the start.

One of the key takeaways here is that PoLP isn’t only about who you are, but also what you need right now.

Why the Principle of Least Privilege Matters

When systems, users, and processes only have access to what they actually need, you reduce the risk of accidents. I have been repeating this enough since the beginning of this article. But how is that risk reduced in practice?

Shrinking the attack surface

The more access you give, the more opportunity an attacker has to do damage. If a compromised account only has access to one database, the damage stops there. If it has access to everything? Good luck.

Limiting malware spread

Malware often spreads laterally, by jumping from one system to the next. Least privilege walls off those paths. Even if one part of your system is compromised, PoLP can help contain the infection.

Preventing privilege escalation

Attackers love finding low-level accounts they can turn into admin accounts. With PoLP in place, there’s less room for escalation tricks, because privileges are already tightly scoped.

Protecting against insider threats

Not every risk is external. Sometimes employees make mistakes, or, unfortunately, act with intent. PoLP helps limit the blast radius in both cases.

Enables faster incident containment

If something goes wrong, knowing exactly who has access to what makes containment way easier. You’re not playing permission bingo while the fire spreads.

Supports compliance

Regulations like GDPR, HIPAA, and PCI DSS require strong access controls. PoLP helps check those boxes by making sure only the right people can access sensitive data.

Improves operational clarity

When everyone has just enough access to do their job, it’s easier to audit, easier to reason about, and way less prone to "privilege creep" (those lingering permissions no one remembers granting, and are probably not needed anymore but stay on just because).

If you’re looking to build a stronger foundation around these kinds of practices, our Introduction to Data Security course covers core principles like PoLP, encryption, and secure system design in more depth.

Principle of Least Privilege Example in Action

Ok, enough theory. Let’s have a look at a practical example of PoLP.

We are in a mid-sized tech company, and a last-minute incident comes in: a bug in production is breaking the customer dashboard. Three people are pulled into the task: Corey, Luca, and Sam. Each has a very different role, and crucially, a very different level of access.

Corey - Frontend Developer

Corey wrote the UI for the dashboard, so he’s brought in to investigate. He has:

- Access to the frontend codebase and the CI/CD pipeline for the web app.

- Read-only access to logs from the last deployment.

- No direct access to production databases or cloud infrastructure.

Corey identifies that a recent change to how customer names are rendered might be failing because of unexpected null values from the API. He flags it for further digging, but he can’t (and shouldn’t) be able to SSH into prod or poke at the database himself. His access is scoped exactly to his role: UI code, logs, and nothing dangerous.

Luca - Site Reliability Engineer

Luca handles infrastructure. When Corey raises the flag, Luca jumps in to trace the issue deeper. He has:

- Access to the Kubernetes dashboard and cluster logs.

- The ability to restart services, roll back deployments, and temporarily scale systems.

- Just-in-time access to read from production databases, granted only through an internal access approval tool.

Luca uses his access to check the API service logs and notices that a recent migration caused a small data inconsistency. To confirm it, he requests time-limited database access, gets it approved, reads the affected rows, and then his elevated access expires automatically after 30 minutes.

If, like Luca, you’re working with databases, pipelines, or cloud infrastructure, understanding how data systems are built helps you design secure access from the start. Our Understanding Data Engineering course is a solid place to start.

Sam - Finance Lead

Meanwhile, Sam has been asked to inform the customer success team about which users were affected, and what impact this had on their subscriptions and SLAs. She has:

- Access to a dashboard tool powered by a read-only analytics replica of the production database.

- Permissions to export reports but not run custom queries or see any sensitive internal logs.

- No access to production servers, code, or developer tools.

Sam checks the customer IDs flagged in the incident report and pulls a report using the internal dashboard, filtering only by billing tier and usage data. She doesn’t need anything more to do her job, and she couldn’t dig into anything she shouldn’t, even if she tried.

In this example, everyone has what they need, and nothing more. Corey couldn’t accidentally delete a database table. Luca’s elevated permissions were time-boxed and tracked. Sam could respond to stakeholders without ever seeing production infrastructure.

How to Implement the Principle of Least Privilege

Let me start by saying that implementing PoLP doesn’t require you to overhaul everything overnight. Even tiny changes can make a big difference, so it is okay if you start small!

Step 1: Conduct a privilege audit

Before you can tighten access, you need to know who has what. You’ll need to review:

- User accounts (employees, contractors, service accounts)

- Applications and integrations

- Background processes or scripts

- Cloud roles, database users, SSH keys, everything else you can think of.

Look for red flags like shared credentials, root access on default accounts, or roles that haven’t been touched since 2018.

Step 2: Start with minimal privileges

When creating new accounts (human or machine, it doesn’t matter), you need to default to the lowest level of access. Let users or services request more if needed. It’s easier (and safer) to add permissions later than to clean up over-permissioned accounts after something goes wrong.

It might be a little annoying in the first few weeks as you will get a lot of requests, but it should settle down once everyone has completed most of the tasks their role requires once or twice.

Step 3: Enforce separation of privileges

Keep admin and user roles separate. If someone needs both (for instance, a DevOps engineer), use distinct accounts or sessions, one for daily tasks, another with elevated rights for specific actions. This limits the risk of accidental (or malicious) misuse.

Step 4: Implement just-in-time (JIT) privileges

Use tools that allow temporary access elevation, as we discussed previously. This might look like:

- Expiring database credentials

- Cloud roles that auto-revoke after 30 minutes

- Approval workflows tied to specific tasks

Step 5: Monitor and log activities

Logging isn’t just for debugging. Track:

- Who accesses what

- When privilege elevations occur

- Changes to roles or permission groups

This data is absolute gold when it comes to audits, incident response, or just understanding how your systems are used day to day.

Step 6: Regularly review and adjust

Even the best setups drift over time. Job roles change, teams evolve, old tools get retired. Schedule recurring reviews (quarterly is a good start) to clean up unused accounts, adjust permissions, and spot any privilege creep before it becomes a problem.

Challenges and Limitations

In theory, PoLP sounds easy: just don’t give out more access than necessary. In practice? It’s a bit messier, especially in large, fast-moving environments with lots of legacy systems, shifting teams, and a never-ending stream of requests.

Complexity in large organizations

In big companies, no one has a complete picture of who has access to what. Teams overlap, responsibilities blur, and trying to untangle existing permissions can feel a bit too much like playing Jenga. You remove permissions that shouldn’t be needed for Team 1, and that somehow prevents Scott from doing his job. Turns out, Scott covers for Matt from Team 2 when he is on holiday, because that used to be his role until he switched teams last year. Implementing PoLP often requires coordination across departments, which takes time (and a good dose of diplomacy).

Risk of productivity slowdowns

When you restrict access too aggressively, it can lead to bottlenecks. People get blocked waiting for approvals or can’t do their job until someone grants them that one missing permission. This is especially true in small companies, where everyone does a bit of everything. There was one occasion in a startup where, after 3 weeks of waiting 2 hours each time I needed permissions (and I needed at least 5 different ones a week), I just asked for an admin role. I was granted it and had way more access than I needed, but at least I could do my job.

All of that to say that the worst thing you can do is make PoLP feel like red tape. It really needs to be paired with smooth escalation workflows and good communication.

Balancing security and productivity is tricky in general, especially when dealing with legacy systems or growing teams. Our blog post on how to maintain data security explores how to stay secure in practice without slowing everything down.

Legacy applications that want all the things

Some older systems just weren’t built with granular permissions in mind. They expect broad access and can break (or become unusable) when run under strict controls. In these cases, you may need to isolate the app in a sandboxed environment and monitor it closely while planning for longer-term fixes.

Privilege creep is sneaky and monitoring takes effort

Over time, users accumulate access. Someone gets added to a group “just temporarily” and then no one removes them. This slow, silent build-up is called privilege creep, and it’s one of the biggest reasons regular audits matter. What made sense six months ago might be completely unnecessary today. And even if you restrict permissions perfectly, you still need to track who’s using what, when, and why. Without solid logging and monitoring, PoLP becomes harder to enforce, and harder to prove to auditors or during incident response.

Let’s be honest, PoLP isn’t effortless, nor is it particularly interesting to manage, for that matter. We just have to accept that it is worth doing anyway. Like locking our front doors, it adds a small layer of friction in exchange for a whole lot of safety.

Similar Principles and Related Concepts

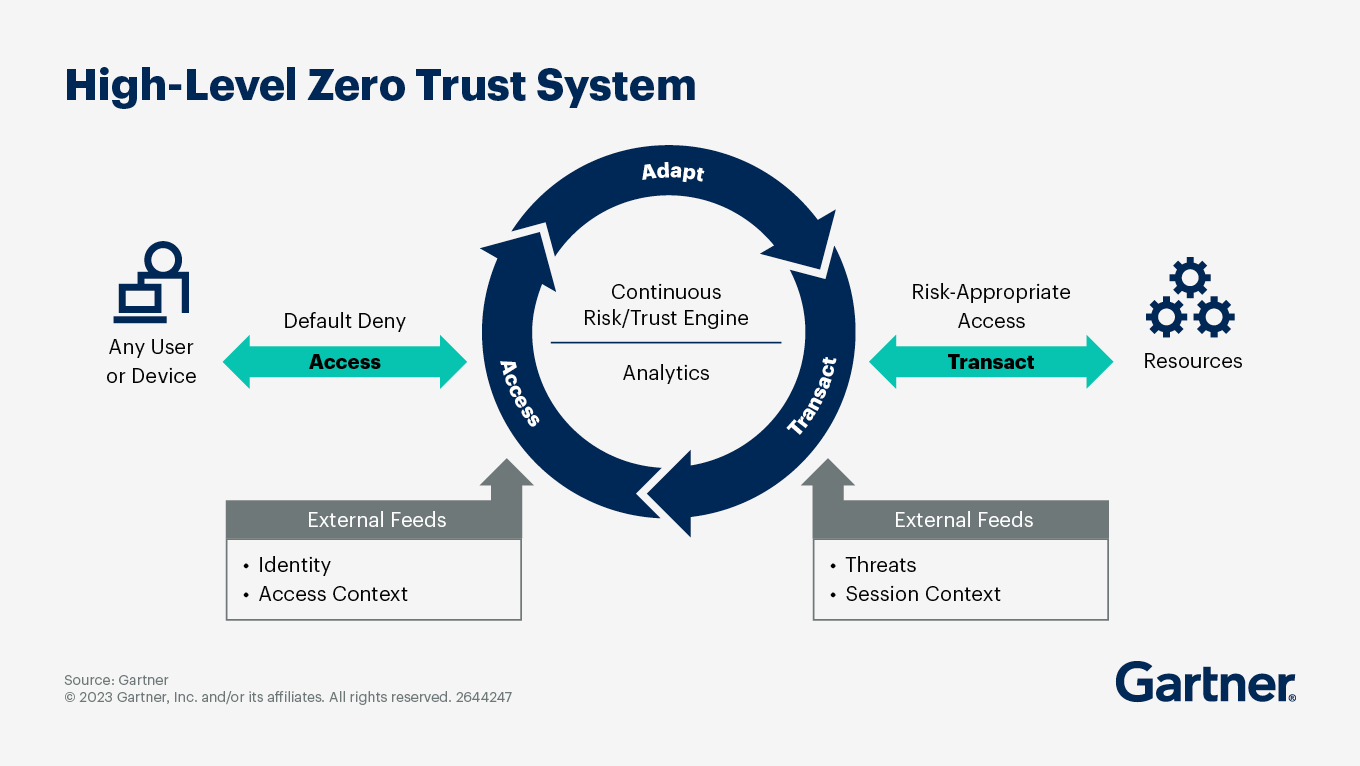

Zero Trust architectures

Zero Trust flips the old security model on its head. Instead of assuming everything inside the network is safe, it treats every user, device, and application as untrusted by default (even if they’re already “inside”!).

In a Zero Trust setup, least privilege isn’t just a good practice, it’s mandatory. Every access request is evaluated in real time, and users or services are granted only the bare minimum access required, often for a limited time and for a specific task.

This is enforced through:

- Dynamic, fine-grained access controls based on who the user is, what device they’re using, where they’re located, and what they’re trying to do. More on this below.

- Policy engines that assess risk continuously, not just at login.

- Just-in-time access combined with detailed logging and automated revocation.

Zero-trust architecture. Source: Gartner

Privilege bracketing

We have touched on privilege bracketing earlier. It is the practice of elevating permissions only for the exact moment a privileged action needs to occur, then dropping back down immediately afterward.

It’s often used in secure environments where full admin access would be too risky to leave open. For example:

- A script runs under a low-privilege user but uses sudo to restart a system service, just for that one command.

- A deployment process temporarily assumes a privileged role to modify infrastructure, then automatically revokes access after completion.

This is especially powerful in DevOps and automation. Keeping background processes running as root 24/7 is a ticking time bomb.

Trusted Computing Base (TCB) minimization

Your Trusted Computing Base includes everything your system depends on to enforce its security. It can include things like the operating system kernel, hypervisors, cryptographic libraries, and access control logic. The smaller your TCB, the easier it is to audit and trust.

PoLP plays into this because over-privileged software expands your TCB. If a logging daemon, for example, can write to arbitrary system files, it becomes part of the TCB (even though it probably shouldn’t be). Reducing privileges reduces the risk that any one component can undermine the system.

You might encounter TCB minimization if you’re into secure OS design, virtualization, embedded systems, or high-security cloud environments.

Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC)

Where traditional access control relies on static roles (like “admin” or “support”), ABAC makes decisions based on attributes, which is contextual data about the user, the resource, or the request.

For example:

- “Allow access if the user is in the HR department and is using a company-issued device and it’s during work hours.”

- “Block access to sensitive data if the request is coming from outside the corporate VPN.”

ABAC is a key part of Zero Trust environments because it allows fine-grained, real-time access decisions that adapt to changing conditions. It doesn’t replace PoLP, it enhances it by layering context permissions on top of minimal baseline ones.

Key Takeaways

Okay, that was a lot! I hope you understand PoLP a little better now. Remember:

- Access should always be intentional. Users, systems, and applications should only have the permissions they actually need to do their job, nothing more, nothing permanent, and nothing “just in case”.

- PoLP isn’t just for people. It applies to service accounts, scripts, APIs, IoT devices, containers…literally anything that can talk to anything else.

- Privilege creep is a thing. Without regular reviews, people accumulate permissions they don’t need anymore. Periodic audits and well-scoped roles help keep things clean.

- Just-in-time and temporary access are your friends. Elevate privileges for the moment, then take them away. The less time a system spends in a high-privilege state, the better.

Although it might sound like it will in the short term, PoLP isn’t about making your life harder. It’s about making mistakes and breaches less costly when they inevitably happen!

Become a Data Engineer

I am a product-minded tech lead who specialises in growing early-stage startups from first prototype to product-market fit and beyond. I am endlessly curious about how people use technology, and I love working closely with founders and cross-functional teams to bring bold ideas to life. When I’m not building products, I’m chasing inspiration in new corners of the world or blowing off steam at the yoga studio.

FAQs

How does PoLP apply to third-party vendors or SaaS integrations?

When connecting external tools or vendors to your systems, you should treat them just like internal users and limit their access to only what’s necessary. Use scoped API keys, restrict IP ranges, and avoid giving broad admin-level access to integrations unless absolutely required.

Can the Principle of Least Privilege be enforced programmatically in CI/CD pipelines?

Yes. Many platforms (like GitHub Actions, GitLab CI, and Jenkins) let you use fine-grained permissions, short-lived tokens, and environment-specific secrets. The goal is to ensure that build and deploy processes only access what they need per environment or step.

Is there a way to visualize privilege relationships in a large system?

Yes, some access management tools offer visualization features that map relationships between users, roles, and resources. You can also generate graphs using IAM policies (in AWS, for example) or use policy-as-code tools like Open Policy Agent (OPA) to validate access logic.