Course

Errors and exceptions can lead to unexpected behavior or even stop a program from executing. Python provides various functions and mechanisms to handle these issues and improve the robustness of the code. In this tutorial, we will learn about various error types and built-in functions with examples.

An error is an issue in a program that prevents the program from completing its task. In comparison, an exception is a condition that interrupts the normal flow of the program. Both errors and exceptions are a type of runtime error, which means they occur during the execution of a program.

In simple words, the error is a critical issue that a normal application should not catch, while an exception is a condition that a program should catch.

Let’s learn more about errors and exceptions by looking at various examples. To easily run these, you can create a DataLab workbook for free that has Python pre-installed and contains all code samples.

Errors in Python

Here is an example of a syntax error where a return outside the function means nothing. We should not handle errors in a program. Instead, we must create a function that returns the string.

return "DataCamp"Input In [1]

return "DataCamp"

^

SyntaxError: 'return' outside function

We have created the function but with the wrong indentation. We should not handle indentation errors at runtime. We can do it manually or use code formatting tools.

def fun():

return "DataCamp" Input In [2]

return "DataCamp"

^

IndentationError: expected an indented block

Exceptions in Python

We have encountered a ZeroDivisionError (Exception). We can handle it at runtime by using try and except blocks.

test = 1/0---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ZeroDivisionError Traceback (most recent call last)

Input In [4], in <cell line: 1>()

----> 1 test = 1/0

ZeroDivisionError: division by zeroNameError exceptions are quite common where a variable is not found. We can also handle the exception either by replacing the variable or printing the warning.

y = test---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

Input In [5], in <cell line: 1>()

----> 1 y = test

NameError

Built-in Python Exceptions

Here is the list of default Python exceptions with descriptions:

AssertionError: raised when the assert statement fails.EOFError: raised when theinput()function meets the end-of-file condition.AttributeError: raised when the attribute assignment or reference fails.TabError: raised when the indentations consist of inconsistent tabs or spaces.ImportError: raised when importing the module fails.IndexError: occurs when the index of a sequence is out of rangeKeyboardInterrupt: raised when the user inputs interrupt keys (Ctrl + C or Delete).RuntimeError: occurs when an error does not fall into any category.NameError: raised when a variable is not found in the local or global scope.MemoryError: raised when programs run out of memory.ValueError: occurs when the operation or function receives an argument with the right type but the wrong value.ZeroDivisionError: raised when you divide a value or variable with zero.SyntaxError: raised by the parser when the Python syntax is wrong.IndentationError: occurs when there is a wrong indentation.SystemError: raised when the interpreter detects an internal error.

You can find a complete list of errors and exceptions in Python by reading the documentation.

Learn about Python exceptions by taking our Object-Oriented Programming in Python course. It will teach you how to create classes and leverage inheritance and polymorphism to reuse and optimize code.

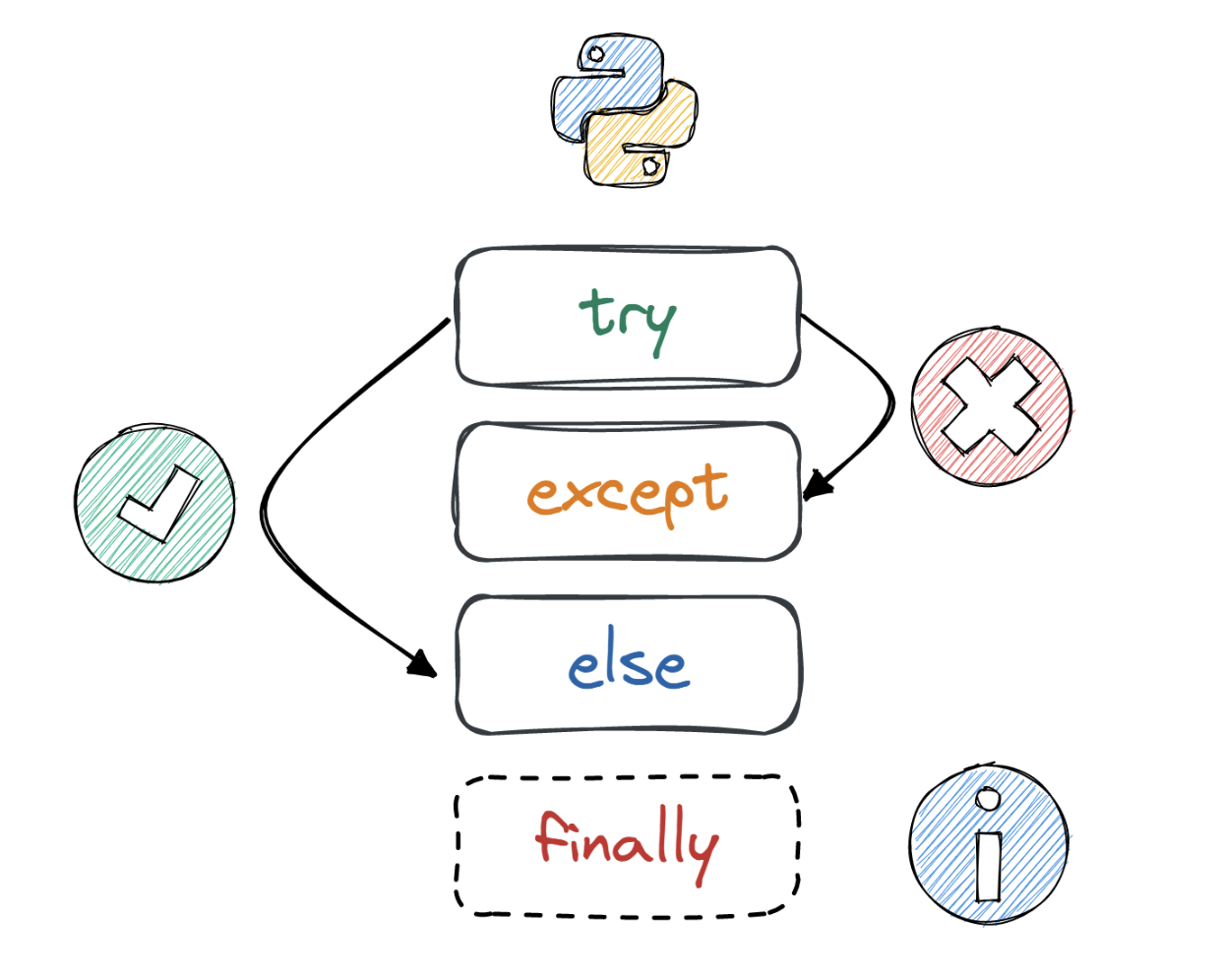

Exception Handling with try, except, else, and finally

After learning about errors and exceptions, we will learn to handle them by using try, except, else, and finally blocks.

So, what do we mean by handling them? In normal circumstances, these errors will stop the code execution and display the error message. To create stable systems, we need to anticipate these errors and come up with alternative solutions or warning messages.

In this section, we will learn what each block does and how we can use them to write robust code.

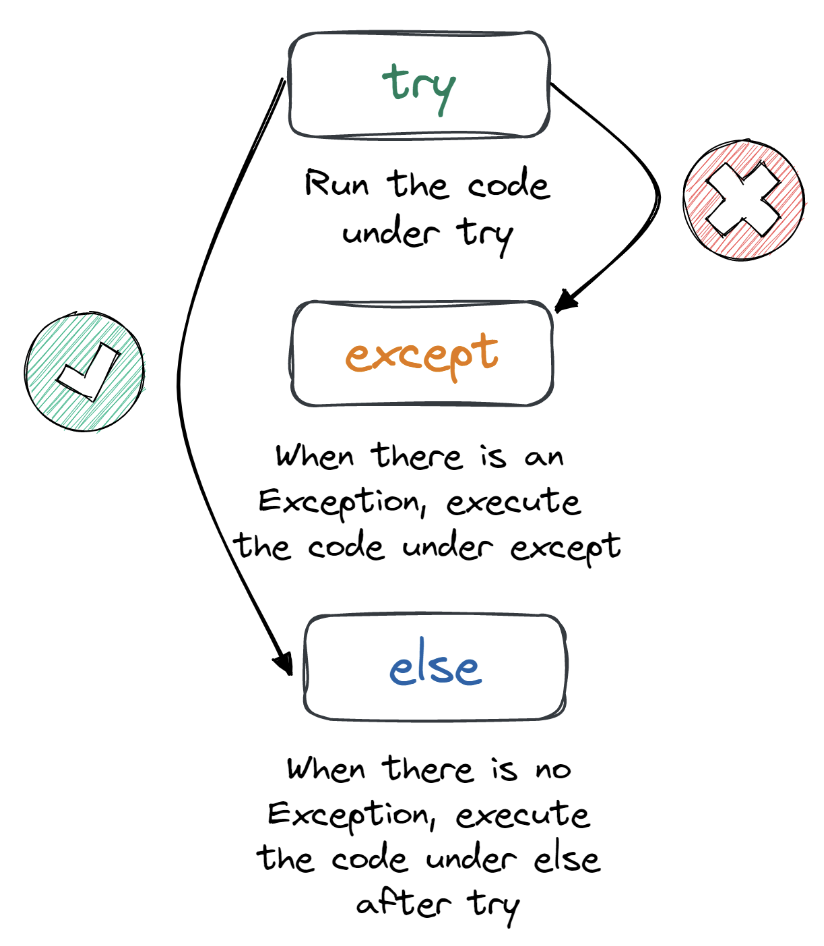

The try and except statement

The most simple way of handling exceptions in Python is by using the try and except block.

- Run the code under the

trystatement. - When an exception is raised, execute the code under the

exceptstatement.

Instead of stopping at error or exception, our code will move on to alternative solutions.

Simple example

In the first example, we will try to print the undefined x variable. In normal circumstances, it should throw the error and stop the execution, but with the try and except block, we can change the flow behavior.

- The program will run the code under the

trystatement. - As we know, that

xis not defined, so it will run the except statement and print the warning.

try:

print(x)

except:

print("An exception has occurred!")An exception has occurred!Multiple except statement example

In the second example, we will be using multiple except statements to handle multiple types of exceptions.

- If a

ZeroDivisionErrorexception is raised, the program will print "You cannot divide a value with zero." - The rest of the exceptions will print “Something else went wrong.”

It allows us to write flexible code that can handle multiple exceptions at a time without breaking.

try:

print(1/0)

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("You cannot divide a value with zero")

except:

print("Something else went wrong")You cannot divide a value with zeroLoading the file example

Now, let’s look at a more practical example.

In the code below, we are reading the CSV file, and when it raises the FileNotFoundError exception, the code will print the error and an additional message about the data.csv file.

Yes, we can print default error messages without breaking the execution.

try:

with open('data.csv') as file:

read_data = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError as fnf_error:

print(fnf_error)

print("Explanation: We cannot load the 'data.csv' file")

[Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'data.csv'

Explanation: We cannot load the 'data.csv' fileThe try with else clause

We have learned about try and except, and now we will be learning about the else statement.

When the try statement does not raise an exception, code enters into the else block. It is the remedy or a fallback option when you expect a part of your script will produce an exception. It is generally used in a brief setup or verification section where you don't want certain errors to hide.

Note: In the try-except block, you can use the else after all the except statements.

Simple example

We are adding the else statement to the ZeroDivisionError example. As we can see, when there are no exceptions, the print function under the else statement is executed, displaying the result.

try:

result = 1/3

except ZeroDivisionError as err:

print(err)

else:

print(f"Your answer is {result}")Your answer is 0.3333333333333333IndexError with else example

Let’s learn more by creating a simple function and testing it for various scenarios.

The find_nth_value() function has x (list) and n (index number) as arguments. We have created a try, except, and else block to handle the IndexError exception.

x = [5,8,9,13]

def find_nth_value(x,n):

try:

result = x[n]

except IndexError as err:

print(err)

else:

print("Your answer is ", result)The list x has four values, and we will test them for the 6th and 2nd indexes.

# Testing

find_nth_value(x,6)

find_nth_value(x,2)- At n=6, the

IndexErrorexception was raised, and we got to see the error default message “list index out of range.” - At n=2, no exception was raised, and the function printed the result which is under the

elsestatement.

list index out of range

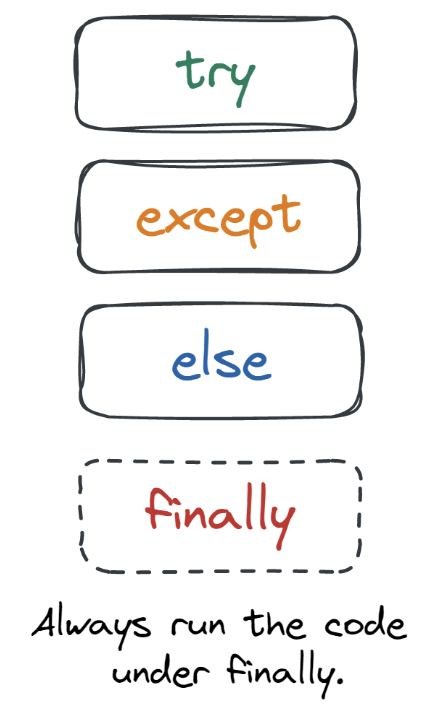

Your answer is 9The finally keyword in Python

The finally keyword in the try-except block is always executed, irrespective of whether there is an exception or not. In simple words, the finally block of code is run after the try, except and else block is final. It is quite useful in cleaning up resources and closing the object, especially closing the files.

The divide function is created to handle ZeroDivisionError exceptions and display the result when there are no exceptions. No matter what the outcome is, it will always run finally to print “Code by DataCamp” in green color.

def divide(x,y):

try:

result = x/y

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Please change 'y' argument to non-zero value")

except:

print("Something went wrong")

else:

print(f"Your answer is {result}")

finally:

print("\033[92m Code by DataCamp\033[00m")

In the first test, we are dividing 1 by 0, which should raise the ZeroDivisionError exception and print the message. As we can see, we have an additional line after the error message.

divide(1,0)Please change 'y' argument to non-zero value

Code by DataCampWhen we add valid input, it displays the result by executing else and finally blocking.

divide(3,4)Your answer is 0.75

Code by DataCampInstead of an integer, we have added a string as a second argument, which has raised an exception, that is different from ZeroDivisionError, with a different message.

divide(1,'g')Something went wrong

Code by DataCampIn all three scenarios, there is one thing in common. The code is always running the print function under the finally statement.

If you are new to Python and want to code like a real programmer, try our Python Programming skill track. You will learn to write efficient code, Python functions, software engineering, unit testing, and object-oriented programming.

Nested Exception Handling in Python

We need nested exception handling when we are preparing the program to handle multiple exceptions in a sequence. For example, we can add another try-except block under the else statement. So, if the first statement does not raise an exception, check the second statement with the other half of the code.

Modifying the divide function

We have modified the divide function from the previous example and added a nested try-except block under the else statement. So, if there is no AttributeError, it will run the else and check the new code for the ZeroDivisionError exception.

def divide(x,y):

try:

value = 50

x.append(value)

except AttributeError as atr_err:

print(atr_err)

else:

try:

result = [i / y for i in x]

print( result )

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Please change 'y' argument to non-zero value")

finally:

print("\033[92m Code by DataCamp\033[00m")In the first scenario, we provide the list of four values x and denominator 3. The script will add 50 to the list, divide the individual value in the list by 3, and display the result.

x = [40,65,70,87]

divide(x,3)The function was successfully executed without raising any exceptions.

[13.333333333333334, 21.666666666666668, 23.333333333333332, 29.0, 16.666666666666668]

Code by DataCampInstead of a list, we have provided an integer to the first argument, which has raised AttributeError.

divide(4,3)'int' object has no attribute 'append'

Code by DataCampIn the last scenario, we have provided the list, but 0 is the second argument that has raised the ZeroDivisionError exception under the else statement.

divide(x,0)Please change 'y' argument to non-zero value

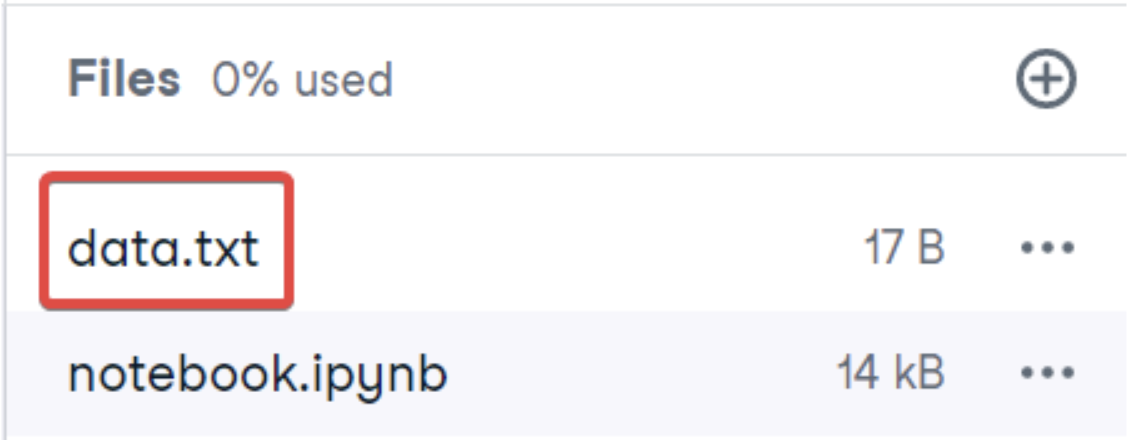

Code by DataCampFile editing example

Let’s look at more practical examples of loading the file, writing a text, and closing the file.

The file_editor() function will:

- Check the

FileNotFoundErrorexception for theopen()function. - If the outer exception is not raised, it will check for the

write()function exception. - No matter what, after opening the file, it will close the file by running the

finallystatement. - If the outer try statement raises the exception, it will return the error message with an invalid file path.

def file_editor(path,text):

try:

data = open(path)

try:

data.write(text)

except:

print("Unable to write the data. Please add an append: 'a' or write: 'w' parameter to the open() function.")

finally:

data.close()

except:

print(f"{path} file is not found!!")In the first scenario, we provide the file path and the text.

path = "data.txt"

text = "DataLab: Share your data analysis in a cloud-based environment--no installation required."

file_editor(path,text)The outer exception is raised.

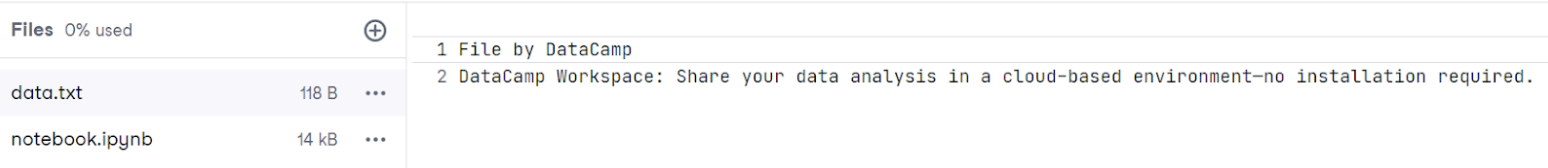

data.txt file is not found!!To resolve the file not found exception, we must create a file data.txt using the Linux echo command.

!echo "File by DataCamp" > "data.txt"

After that, rerun the file_editor() function.

file_editor(path,text)The inner exception is raised, as the write() function is not able to add the text.

Unable to write the data. Please add an append: 'a' or write: 'w' parameter to the open() function.To resolve this issue, we need to change the third line from data = open(path) to data = open(path, 'a'). It will allow us to append the new text to the file.

After rerunning the function, we successfully added the text to the file.

file_editor(path,text)

Nested exception handling is not recommended as it makes exception handling more complex; developers use multiple try-except blocks to create simple sequential exception handling.

Note: you can also add a nested try-except block under the try or except statement. It just depends on your requirements.

Raising Exceptions in Python

As a Python developer, you can throw an exception if certain conditions are met. It allows you to interrupt the program based on your requirements.

To throw an exception, we have to use the raise keyword followed by an exception name.

Raising value error example

We can simply raise exceptions by adding a raise keyword in the if/else statement.

In the example, we raise the ValueError if the value exceeds 1,000. We have changed the value to 2,000, which has made the if statement TRUE and raised ValueError with the custom message. The custom error message helps you figure out the problem quickly.

value = 2_000

if value > 1_000:

# raise the ValueError

raise ValueError("Please add a value lower than 1,000")

else:

print("Congratulations! You are the winner!!")---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

----> 4 raise ValueError("Please add a value lower than 1,000")

5 else:

6 print("Congratulations! You are the winner!!")

ValueError: Please add a value lower than 1,000Raising exception example

We can also raise any random built-in Python exception if the condition is met. In our case, we have raised a generic Exception with the error message.

if value > 1_000:

# raise the Exception

raise Exception("Please add a value lower than 1,000")

else:

print("Congratulations! You are the winner!!")---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Exception Traceback (most recent call last)

----> 3 raise Exception("Please add a value lower than 1,000")

4 else:

5 print("Congratulations! You are the winner!!")

Exception: Please add a value lower than 1,000Handling raised exception example

We can also create our custom exception and handle the exception by using the try-except block.

In the example, we have added a value error example under the try statement.

So, how will it work? Instead of throwing the exception and terminating the program, it will display the error message we provided.

value = 2_000

try:

if value > 1_000:

# raise the ValueError

raise ValueError("Please add a value lower than 1,000")

else:

print("Congratulations! You are the winner!!")

# if false then raise the value error

except ValueError as e:

print(e)This type of exception handling helps us prepare for errors not covered by Python and are specific to your application requirement.

Please add a value lower than 1,000What's New in Python 3.10 and 3.11 for Exception Handling?

Some important new developments have been added to newer Python versions like 3.10 and 3.11 since the blog post was originally written:

1. Structural pattern matching in Python 3.10: Python 3.10 introduced structural pattern matching, which can be used to handle exceptions more elegantly by matching error types in a match statement. This is particularly useful when dealing with multiple exception types in a more readable way. Example:

try:

result = 1 / 0

except Exception as e:

match e:

case ZeroDivisionError():

print("You cannot divide by zero.")

case NameError():

print("Variable not defined.")

case _:

print("An unexpected error occurred.")

2. Fine-grained error locations in tracebacks (Python 3.11): Tracebacks in Python 3.11 now show precise error locations, making it easier to debug exceptions.

- Before Python 3.11:

value = (1 + 2) * (3 / 0)- Traceback:

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

- Python 3.11: Tracebacks pinpoint the exact sub-expression causing the exception:

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

(1 + 2) * (3 / 0)

^3. Exception groups and except* (Python 3.11): Python 3.11 introduced exception groups to handle multiple exceptions in a single block using except*. This is useful for managing asynchronous code or scenarios where multiple exceptions might be raised. Example:

try:

raise ExceptionGroup("Multiple errors", [ValueError("Bad value"), TypeError("Bad type")])

except* ValueError as ve:

print(f"Handling ValueError: {ve}")

except* TypeError as te:

print(f"Handling TypeError: {te}")4. add_note method for exceptions (Python 3.11): Exceptions now have an add_note() method, which allows developers to add custom notes to exceptions for better debugging. Example:

try:

raise ValueError("Invalid input")

except ValueError as e:

e.add_note("This happened while processing user input.")

e.add_note("Consider validating input before processing.")

raise- Traceback:

ValueError: Invalid input

Notes:

- This happened while processing user input.

- Consider validating input before processing.5. PEP 654: Better handling of nested exceptions: With exception groups, nested exceptions are now easier to debug and handle, especially in complex workflows like multiprocessing or asynchronous tasks.

Conclusion

Both unit testing and exception handling are the core parts of Python programming that make your code production-ready and error-proof. In this tutorial, we have learned about exceptions and errors in Python and how to handle them. Furthermore, we have learned about complex nested try-except blocks and created custom exception blocks based on requirements.

These tools and mechanisms are essential, but most of the work is done through simple try and except blocks. Where try looks for exceptions raised by the code and except handles those exceptions.

If this is confusing and you don’t know where to start, complete our Introduction to Functions in Python course to understand scoping, lambda functions, and error handling. You can also enroll in the Python Programmer career track to gain career-building skills and become a professional Python developer.

Learn Python From Scratch

FAQs

What is the difference between an error and an exception in Python?

An error in Python is typically a more severe problem that prevents the program from continuing, such as a syntax error, which indicates that the code structure is incorrect. An exception, on the other hand, is a condition that interrupts the program's normal flow but can be handled within the program using try-except blocks, allowing the program to continue executing.

Can you catch multiple exceptions in a single try-except block?

Yes, Python allows you to catch multiple exceptions in a single try-except block by using a tuple of exception types. For example: except (TypeError, ValueError):. This will handle either a TypeError or a ValueError in the same block.

How can you create a custom exception in Python?

You can create a custom exception by defining a new class that inherits from the built-in Exception class. For example:

class MyCustomError(Exception):

passWhat is the purpose of the else block in a try-except structure?

The else block is executed if the try block does not raise an exception. It is useful for code that should be run only if the try block succeeds, keeping the code clean and separating the error handling from the normal execution path.

Why is the finally block important in exception handling?

The finally block is always executed, regardless of whether an exception is raised or not. It is typically used for cleanup actions, such as closing files or releasing resources, to ensure that these actions are performed under all circumstances.

How can you suppress exceptions in Python?

You can suppress exceptions by using the contextlib.suppress context manager. It allows you to specify exception types that should be ignored. For example:

from contextlib import suppress

with suppress(FileNotFoundError):

open('non_existent_file.txt')What happens if an exception is not caught in a Python program?

If an exception is not caught, it propagates up the call stack, and if it remains unhandled, it terminates the program, printing a traceback to the console that shows where the exception occurred.

Can you re-raise an exception after catching it?

Yes, you can re-raise an exception using the raise statement without arguments in an except block. This is useful when you want to log an error or perform some other actions before allowing the exception to propagate further.

Is there a way to handle all exceptions in Python?

While it's possible to catch all exceptions using a bare except: clause, it's generally not recommended because it can catch unexpected exceptions and make debugging difficult. It's better to catch specific exceptions or use except Exception: to avoid catching system-exiting exceptions like SystemExit and KeyboardInterrupt.

How do you differentiate between a syntax error and runtime exceptions in terms of when they occur?

Syntax errors are detected at compile time, meaning the Python interpreter catches these errors before the program starts executing. Runtime exceptions occur during program execution when the interpreter encounters an operation it cannot perform, such as dividing by zero or accessing a non-existent variable.

As a certified data scientist, I am passionate about leveraging cutting-edge technology to create innovative machine learning applications. With a strong background in speech recognition, data analysis and reporting, MLOps, conversational AI, and NLP, I have honed my skills in developing intelligent systems that can make a real impact. In addition to my technical expertise, I am also a skilled communicator with a talent for distilling complex concepts into clear and concise language. As a result, I have become a sought-after blogger on data science, sharing my insights and experiences with a growing community of fellow data professionals. Currently, I am focusing on content creation and editing, working with large language models to develop powerful and engaging content that can help businesses and individuals alike make the most of their data.