Course

Git is a popular version control system (VCS) used in software development to track changes to files over time. It facilitates collaboration by allowing developers to work simultaneously without overwriting each other's contributions. Because all developers maintain complete local copies of the project's history, individuals can work independently offline and safely merge their changes when ready.

A remote repository, or remote, is a version of your Git project that's hosted in the cloud through an online hosting service such as GitHub or BitBucket.

This article will explore Git remotes in more detail. If you’re just getting started with Git, consider reading our Git tutorial for beginners.

What is a Git Remote?

A Git remote provides a centralized location where a repository can be stored, shared, and accessed by others. Users can push their local changes to the remote and pull updates made by teammates from the remote. Remotes can also be useful for backing up code and deploying code to production environments.

A local repository lives on your own computer, so you can write code, make commits, and test changes locally. A remote repository, located online, is used to share code, collaborate with others, and back up your work. In this article, we’ll see how to sync changes between local and remote repos using Git commands.

Git workflow

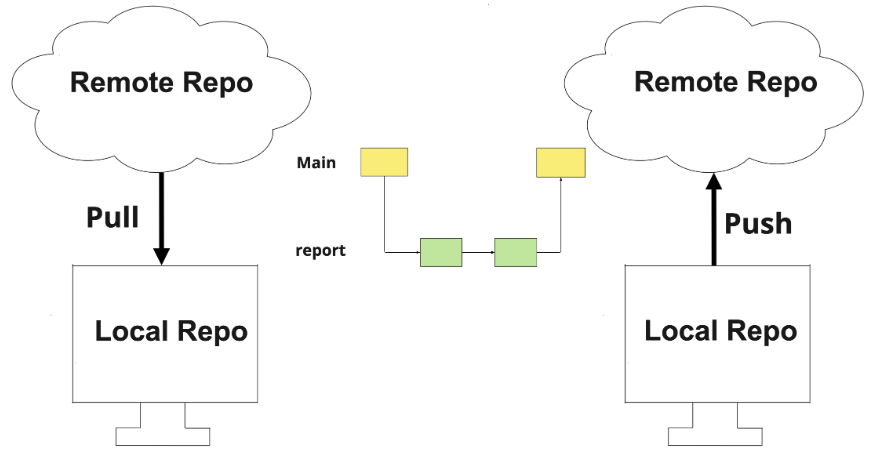

A typical Git workflow starts by “cloning” a remote repository to your local machine. After cloning, you may create a new branch to work on a feature or fix, make modifications, and commit those changes locally.

Once your work is ready, you “push” the branch to the remote and open a pull request for review. After approval, merge changes into the main branch.

Throughout the process, you regularly “pull” updates to keep your local repository in sync with the remote.

A typical Git workflow (Image from Introduction to Git Course)

Let’s look at this process in more detail.

Cloning a repo

Let’s suppose you want to make a copy of a remote repository, a process known as “cloning” the repo. With a local copy, you can modify the code and test new features.

To use Git, make sure you have it installed, then open a terminal and use this command: git clone <URL>.

For example, to clone a project called “project” from a GitHub page with username “datacamp,” use

git clone https://github.com/datacamp/project.gitDefault remote: 'origin'

When you clone a repository, Git creates a default remote named origin. This label origin acts as an alias for the URL of the repository you cloned from.

In typical Git workflows, when you run commands like git push or git pull, Git assumes you're referring to origin unless you specify a different remote. This simplifies syncing changes between your local copy and the shared repository. We'll take a closer look at pushing and pulling a bit later in this article.

Managing Git Remotes

Common remote management tasks include viewing existing remotes using git remote and adding a new remote with git remote add.

Viewing existing remotes

To view existing remotes, use the command git remote.

git remote

>> originIn our example, the remote alias origin is listed, but its URL is not shown. If you want to see the URL associated with each remote, use the -v flag.

git remote -v

>> origin https://github.com/datacamp/project.git (fetch)

>> origin https://github.com/datacamp/project.git (push)Adding a new remote

You might want to connect your local repository with another remote. For example, if you’ve forked a project, you may want to keep track of changes in the original repository in addition to changes to the main remote. Or, you might want to push your code to multiple platforms, such as GitHub and GitLab.

To add a new remote, use the command git remote add <name> <URL>. Let’s add a new remote named new_remote.

git remote add new_remote https://github.com/datacamp/projectNaming the remote is useful so that you won’t need to repeatedly type in the URL when merging.

Renaming and removing remotes

Renaming a remote is straightforward. Use the command git remote rename <old-name> <new-name>. For instance,

git remote rename new_remote original_remoteTo verify the remote was renamed, list the remotes with git remote.

To removing a remote, use git remote remove <name>. For our example:

git remote remove new_remoteNow, list the remotes to verify.

git remote

>> originWe see the only remote is origin.

Working with Remote Branches

A branch in Git is a path independent of main that allows you to work on changes separately from the main version of your project. Once your work is complete and reviewed, you can merge the branch back into the main project.

Listing remote branches

To list remote branches, we use the command git branch -r.

git branch -r

>> origin/HEAD -> origin/main

>> origin/mainLet’s interpret the output. The line origin/main indicates there is a remote branch named main on the remote origin. The line origin/HEAD -> origin/main shows that the default branch on the remote is origin/main. So, this output tells you that main is the default branch on the origin remote, and it's currently the only remote branch listed.

Tracking a remote branch

You’ll often want to connect a local branch to a remote branch to keep your code in sync. When a local branch tracks a remote branch, you can pull and push changes without needing to specify the remote and branch names each time.

Git also keeps track of how many commits your local branch is ahead or behind the remote, making it easier to manage changes.

The command git checkout --track origin/<branch-name> creates a new local branch that tracks the specified remote branch. It sets up a local branch with the same name as <branch-name> and links it to the remote version. This way, future git pull and git push commands will automatically interact with the correct remote branch. You can learn more about Git Push and Pull in our tutorial.

Fetching and pulling from remotes

To keep your local branch up synchronized with other developers’ changes, you need to pull content into your local branch. “Pulling” means downloading the newest changes from the corresponding branch on the remote and merging those changes into your local version of that branch. This ensures you're working with the most current code.

Let’s suppose we want to pull all branches from the remote named origin. This is done using the command git fetch origin. If you only want to fetch a specific branch, such as main, specify it, as in git fetch origin main.

After fetching, you still need to synchronize the content by merging the fetched changes into your current local branch. To do this, run git merge origin/<branch-name>, replacing <branch-name> with the name of the branch you fetched. For example, to merge changes from the remote main branch, you would use git merge origin/main.

Since it’s common to fetch and merge in sequence, Git provides a single command that does both: git pull. For example, to fetch and merge changes from the main branch on the remote named origin, you can use git pull origin main.

When should you use fetch and merge and when should you use pull? The two-step process of fetch and merge give you more control over the update process. Fetching lets you see what has changed on the remote before merging it into your local branch. This is helpful if you want to review updates, compare differences, or handle potential conflicts carefully.

Use pull when you’re confident that the remote changes are safe to merge right away and you want to update your branch quickly. It’s convenient and combines both steps into one, but it gives you less visibility before the merge happens.

Pushing to a remote repository

“Pushing” content into a remote from a local branch means you're sending your local changes to the corresponding branch on the remote repository. This updates the remote with your latest work so others can see it, pull it, or build on it. Pushing shares your contributions and helps keep the remote repository up to date for everyone working on the project.

Uploading local changes to the remote is a three-step process.

1. Use git add to stage the files you want to include. To add all changes, use

git addTo add a specific file, specify the filename.

git add <filename>2. Commit your changes. Include a message to describe what you did.

git commit -m “Your commit message here”3. Push to the remote.

git push origin branch-namePractical Examples

Let’s look at some practical examples: cloning a repo, and collaborating with multiple remotes.

Cloning a repository

Here is a step-by-step guide to cloning a repo.

- Get the repository URL. Copy the URL of the repository you want to clone. This URL is available from your cloud provider, such as GitHub or BitBucket.

- Choose a directory. Navigate to the folder on your computer where you want the repo to be copied.

- Clone the repository. Run the command

git clone <URL>. For example, rungit clone https://github.com/datacamp/project.This creates a new folder named project with the repo contents inside. - List configured remotes. After cloning, check the remotes with the command

git remote.In our example, you’ll seeorigin, which is the default name Git gives to the remote you cloned from and its URL.

Collaborating with multiple remotes

When contributing to an open-source project or collaborating through a personal copy (fork), it's common to work with two remotes: origin, which is your fork of the repo, and upstream, which is the repo you forked from. Typically, you have write access to origin but not upstream.

There are some best practices for managing multiple remotes to keep in mind.

- Add the

upstreamremote. After cloning your fork, keep track of the the original repo as upstream:git remote add upstream <URL>. - Keep your fork up-to-date. Regularly fetch changes from the upstream repo using the command git fetch upstream. Then merge or rebase those changes into your local branch.

- Avoid pushing to the

upstreamrepo. You typically don’t have (or need) push access to the upstream repo. All your changes should be pushed toorigin, and pull requests made from there. - Use descriptive branch names. Keep your local branches organized. It is a good idea to name them after the feature or issue you’re working on.

- Check your remotes. Use

git remote -vto review your remote setup and verify that URLs fororiginandupstreamare correct. - Stay in sync before working. Before starting new work, always pull the latest changes from upstream into your main branch to stay current and avoid conflicts later.

Git Remote Best Practices and Tips

Here are some best practices you should follow when using Git remote:

Keeping remotes updated

Regularly fetching changes helps ensure your local copy of the repository stays up to date with the remote version. By running git fetch, you download any new changes from the remote without affecting your current branch.

This keeps you aware of what colleagues pushed, allows you to compare changes, and helps you prepare for any necessary updates or merges. Consistent fetching reduces the chance of conflicts and keeps your collaboration workflow running smoothly.

Over time, as branches are deleted from the remote repository, your local Git setup may still show those old branches as remote-tracking branches. These are known as “stale” remote-tracking branches.

To clean up your branches, run git remote prune origin to remove any remote-tracking branches that no longer exist on the origin remote.

Doing this regularly helps keep your local repository organized, makes it easier to find relevant branches, and ensures you're not referencing outdated work.

Handling conflicts with remotes

Remote conflicts can be difficult to resolve. The best solution is to prevent them by making sure multiple people aren't working on the same parts of the code at the same time. However, this isn’t always possible.

Despite our best intentions, conflicts can and do happen. When they do occur, follow this plan to handle them effectively.

- Use

git statusto see what conflicts need your attention. - Open the conflicted files and edit them to resolve the changes.

- Use a merge tool. Tools like VS Code or

git mergetoolshow side-by-side comparisons and let you choose which version of the code to keep. - Communicate with the team. If the conflict is unclear, check with your colleagues before resolving the issue. Make sure you understand which lines to keep and which to remove.

- Test your code after resolving the conflict to ensure that nothing is broken and everything works as expected.

- Commit your changes. After resolving all conflicts, stage the files and make a commit to complete the merge.

Rebase

Using git pull --rebase can reduce the likelihood of complex merge conflicts by applying your changes on top of the latest remote commits.

When you use git pull --rebase, Git first fetches the latest changes from the remote, then applies your local commits on top as if your work happened afterward.

This approach helps create a cleaner, linear commit history and can reduce the chances of messy merge conflicts.

Instead of creating a merge commit that combines the histories, rebase makes it look like your changes were made after the remote updates. You can learn more in our Git Rebase tutorial.

Conclusion

Git remotes are crucial to collaborative development, connecting local repositories with shared codebases. In this guide, we’ve covered essential remote operations, including setting up, synchronizing through fetch, pull, and push commands, and managing multiple remote connections.

Mastering the concepts we’ve covered can help you collaborate more efficiently, maintain a clear project history, and contribute to your development team.

For further information related to git remote branches, check out DataCamp’s resources.

- Git Checkout Remote Branch: Step-by-Step Guide

- Git Push and Pull Tutorial

- Git Pull Force: How to Overwrite a Local Branch With Remote

- Introduction to Git Course

- Intermediate Git Course

- Advanced Git Course

- Introduction to GitHub Concepts

- GitHub and Git Tutorial for Beginners

- How to Learn Git in 2025: A Complete Guide for Beginners

- Git Cheat Sheet

Git Remotes FAQs

What is a Git remote?

A Git remote is a link to a repository that is hosted on a server, often on platforms like GitHub, GitLab, or Bitbucket.

What is the remote called when you clone a repository?

By default, the remote is aliased as origin.

How do I see which remotes are configured?

The command git remote -v shows the names and URLs of all remotes linked to your project.

How do I add a new remote?

Use the command git remote add <name> <url>. For example,

git remote add upstream https://github.com/user/project.git

What happens if I push to the wrong remote?

You’ll send your changes to the wrong repository. It’s a good idea to double-check your remote names using git remote -v.