Track

Python's map() function is a powerful built-in tool that enables functional programming patterns for data transformation. If you want to process large datasets, clean text data, or perform bulk calculations, then the map() function can be very helpful to boost productivity.

In this tutorial, I’ll show you the syntax, practical applications, and advanced techniques of Python’s map() function. We’ll also look at lazy evaluation for memory efficiency and compare map() to alternatives like list comprehension, and discuss best practices for optimal performance.

Understanding iterators is just the first step in writing efficient code. To truly master data manipulation, you need a complete Python programming toolbox that includes everything from error handling to advanced iterables.

Python map() Syntax

Before looking into the usage of the map() function, let’s take a look at the way this function works. Understanding its syntax and behavior can help us apply it more effectively.

map() function basics

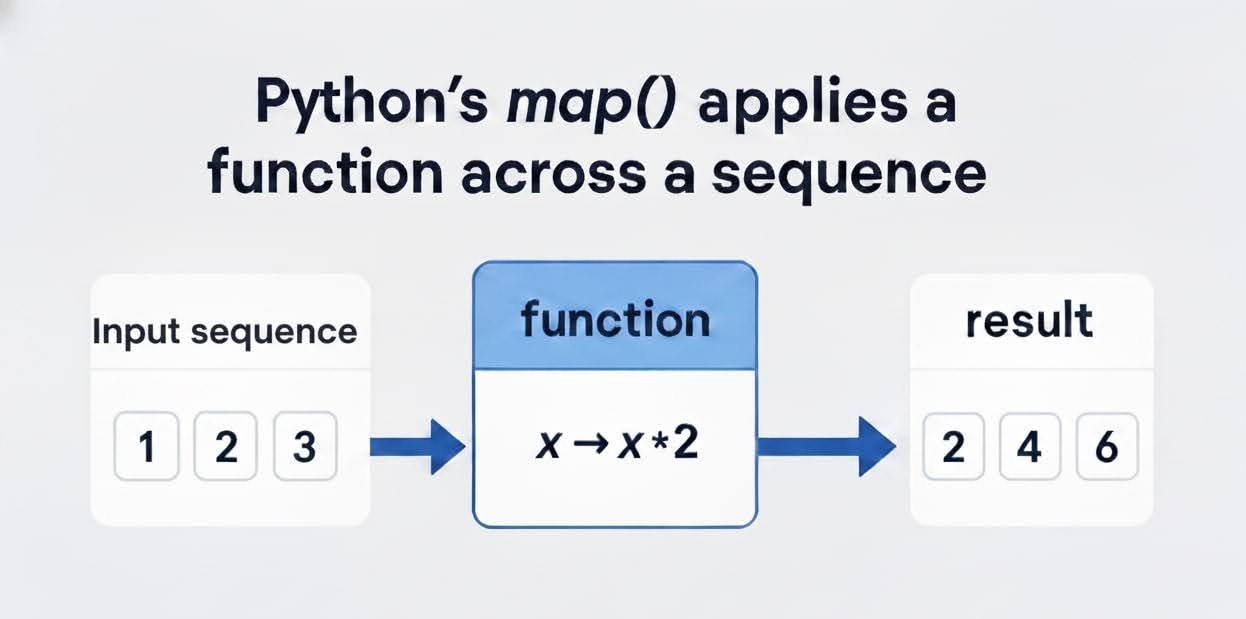

The map() function is a built-in Python utility that applies a specified function to every item in an iterable (like a list, tuple, or string) and returns an iterator with the transformed results. As a result, it promotes immutability and code reusability, which is important in data processing pipelines and preprocessing features for machine learning models.

The syntax is straightforward, as shown below:

map(function, iterable, ...) The function, which can be a built-in function like len() or a custom one, is applied to every item in the iterable. We can also add multiple iterables to enable parallel mapping. We’ll get to that later.

Unlike eager evaluation (which computes everything upfront), map() employs lazy evaluation. It returns a map object, an iterator that yields values on demand. This defers computation until you iterate over it, saving memory for large datasets.

For a quick visual, consider this simple example of squaring numbers:

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]

squared = map(lambda x: x**2, numbers)

print(list(squared))[1, 4, 9, 16]Parameter values and return values

The map() function requires at least two parameters: a callable function and an iterable. Optional additional iterables allow broadcasting the function across zipped sequences, which are perfect for vectorized operations akin to NumPy's apply_along_axis().

In Python 3, map() returns a map object, an iterator subclass, rather than a list. This shift enhances memory efficiency, as it doesn't allocate space for the entire result upfront. To materialize results, convert them explicitly:

-

To a list:

list(map(function, iterable)) -

To a set:

set(map(function, iterable)) -

Iterate directly:

for item in map(function, iterable): ..

Here's a code snippet demonstrating conversion:

words = ['python', 'data', 'science']

# Converts map object to list

lengths = list(map(len, words))

print(lengths)[6, 4, 7]For a quick overview of different Python operations used throughout this tutorial, I recommend you take a look at this Python cheat sheet.

Transition from Python 2 to Python 3

In Python 2, map() eagerly returned a list, which could bloat memory for large inputs, a common pitfall in legacy data scripts. Python 3's lazy map object changed this, aligning with iterator protocols for scalability in big data environments like PySpark.

The implications? Smoother handling of massive datasets without Out of Memory (OOM) errors, though it requires explicit conversion for indexing. For instance, my_map[0] won't work, so we have to use next(iter(my_map)) instead.

If you are accustomed to list-based logic, take a look at the Python for MATLAB users course to ease your shift from vectorized operations to Python iterators.

How to Use map() in Python

Now that we’ve looked at the basics, let's implement the map() function. We’ll look at the most common ways to apply map(), from simple built-in functions to more complex multi-iterable transformations.

Basic map() usage

The most straightforward way to use map() is with a built-in function. Let's say you have a list of strings and you want to find the length of each one. To apply the map() function:

-

Identify your iterable:

words = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry'] -

Identify your function: The built-in

len()function. -

Apply map():

map(len, words) -

Convert to a list:

list(map(len, words)

Let’s see the code below:

words = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry']

# Apply the len() function to each item in the list

lengths_map = map(len, words)

# Convert the map object to a list to see the results

lengths_list = list(lengths_map)

print(lengths_list)[5, 6, 6]As we can see, this is more concise than writing a for loop, appending to a new list, and managing the state of that list.

Using map() with lambda functions

Often, the operation you want to perform is simple and short-lived. Instead of defining a full function with def, you can use a lambda function, which is a small, anonymous, one-line function.

This is extremely common in data processing. For instance, if you want to square a list of numbers, a lambda function is the perfect choice. Let’s see that with an example below:

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

# Use a lambda function to square each number

squared_map = map(lambda x: x * x, numbers)

squared_list = list(squared_map)

print(squared_list)[1, 4, 9, 16, 25]Using lambda functions with map() is recommended in the following cases:

-

The transformation is simple (ideally, a single expression).

-

The function is not reused elsewhere in your code.

To know more about lambda functions, check out this detailed interactive Python lambda tutorial.

Using map() with user-defined functions

For more complex or repeated transformations, use a custom function defined with the def keyword. It makes your code more readable, modular, and easier to test.

Let’s say you have a list of temperatures in Celsius and you need to convert them to Fahrenheit. We can do that as follows:

def celsius_to_fahrenheit(c):

# The formula is (Celsius * 9/5) + 32

return (c * 9/5) + 32

celsius_temps = [0, 10, 25, 30.5, 100]

# Pass the user-defined function to map()

fahrenheit_map = map(celsius_to_fahrenheit, celsius_temps)

fahrenheit_list = list(fahrenheit_map)

print(fahrenheit_list)[32.0, 50.0, 77.0, 86.9, 212.0]Using a function with a descriptive name, such as celsius_to_fahrenheit(), clearly documents the code's intent, making it a best practice for any specialized business logic.

Using map() with multiple iterables

One powerful feature of map() is its ability to process multiple iterables simultaneously. To do this, your function must accept the same number of arguments as the number of iterables you provide.

Let's say you have two lists of numbers and you want to add them together element-wise:

list_a = [1, 2, 3, 4]

list_b = [10, 20, 30, 40]

# The lambda function now takes two arguments, x and y

sums_map = map(lambda x, y: x + y, list_a, list_b)

sums_list = list(sums_map)

print(sums_list)[11, 22, 33, 44]Now, what if the iterables have different sizes? The map() function will stop processing as soon as the shortest iterable runs out, so the output will have the length of the shortest iterable. Let’s see that in action with an example:

list_a = [1, 2, 3] # Length 3

list_b = [10, 20, 30, 40] # Length 4

# map() will stop after the 3rd element

short_map = map(lambda x, y: x + y, list_a, list_b)

print(list(short_map))[11, 22, 33]This behavior is predictable and useful, preventing IndexError exceptions. If you need to process all elements and fill in a default value for the shorter list, you can use itertools.zip_longest().

Next, let’s see some everyday use cases for the map() function.

Common Python map() Use Cases

The map() function is versatile and is very useful for many common data processing and cleaning tasks. Let's take a look at where you'll find it most useful.

Performing calculations on lists

This is the most classic use case. When you have a list of numbers and need to apply a uniform mathematical operation to every single element, map() is a clean and efficient solution.

We already saw a great example of this with the conversion from Celsius to Fahrenheit in the previous section. Another common scenario is applying a financial formula, like calculating sales tax or converting currencies.

Imagine you have a list of product prices in USD and you need to convert them to EUR. We can do that as shown below:

def usd_to_eur(price_usd):

# Assuming a static exchange rate for this example

EXCHANGE_RATE = 0.92

return round(price_usd * EXCHANGE_RATE, 2)

prices_usd = [99.99, 150.00, 45.50, 78.25]

prices_eur_map = map(usd_to_eur, prices_usd)

print(list(prices_eur_map))[91.99, 138.0, 41.86, 71.99]This pattern is far more readable than a for loop, especially when the conversion logic is complex and best kept inside its own function.

Processing strings in bulk

Data cleaning often involves processing large volumes of text data. You might have thousands of text entries that need to be normalized before analysis. The map() function is perfect for applying string methods to an entire list.

For example, let's clean a list of names by removing unwanted whitespace and standardizing the case:

raw_names = [' Alice Smith ', ' bob johnson', 'Charlie Brown ', ' david lee']

# Use map() with the built-in .strip() method

cleaned_names_map = map(str.strip, raw_names)

# Now chain another map() to convert to title case

# Note: we apply the second map to the *results* of the first map

final_names_map = map(str.title, cleaned_names_map)

print(list(final_names_map))['Alice Smith', 'Bob Johnson', 'Charlie Brown', 'David Lee']This ability to chain map() operations (because each one returns an iterator) is important for handling efficient data pipelines.

Filtering and mapping data

Often, you don't want to transform every item. You only want to transform items that meet a certain condition. This is a common pattern in data analysis, and it's easily solved by combining map() with Python's filter() function.

The filter(function, iterable) function works similarly to map(), but it only returns items for which the function returns True.

Let's say we have a list of sensor readings, and we want to square only the positive values, ignoring any negative ones (which might be errors). We can do that by:

-

Filter: First, use

filter()to get only the positive numbers. -

Map: Then, use

map()to apply the squaring function to the filtered results.

readings = [10, -5, 3, -1, 20, 0]

# 1. Filter out the negative numbers

positive_readings = filter(lambda x: x > 0, readings)

# 2. Map the squaring function to the filtered iterator

squared_positives = map(lambda x: x * x, positive_readings)

print(list(squared_positives))[100, 9, 400]Because both map() and filter() are lazy, this two-step process is extremely memory-efficient. No intermediate lists are created. This filter-then-map pattern is a powerful alternative to a more complex Python list comprehension.

Practical map() Examples in Action

Now that we've seen the basic concepts and common use cases, let's take a look at some specific practical examples that demonstrate how the map() function provides a clean and efficient syntax for various data transformation tasks.

Converting to uppercase

This is a classic string processing task. Given a list of strings, you can use the map() function with the built-in str.upper() method to convert every item to uppercase, as shown below:

words = ['data science', 'python', 'map function']

# Apply the str.upper method to each item

upper_words = map(str.upper, words)

print(list(upper_words))['DATA SCIENCE', 'PYTHON', 'MAP FUNCTION']Extracting the first character from strings

Sometimes you need to extract a specific piece of information from each item. Here, we can use a lambda function to get the first character (at index 0) from each string in a list.

names = ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie']

# Use a lambda function to get the character at index 0

first_chars = map(lambda s: s[0], names)

print(list(first_chars))['A', 'B', 'C']Removing whitespaces from strings

As we saw in the section about processing strings, cleaning whitespace is a fundamental step in text data preparation. map() with str.strip() is the most Pythonic way to do this.

raw_data = [' value1 ', ' value2 ', ' value3']

# Apply the str.strip method

cleaned_data = map(str.strip, raw_data)

print(list(cleaned_data))['value1', 'value2', 'value3']For more ways to manage string and list data, this interactive tutorial on Python list functions and methods provides many examples.

Updating data in frameworks (e.g., Django)

In a web or data-driven application, you often receive data as a list of dictionaries (like a JSON payload). The map() function can be used to prepare the data for a database update, such as in Django or when working with MongoDB.

Let's imagine we have a list of dictionaries representing product updates, and we need to add a processed timestamp to each one before sending it to the database:

import datetime

def add_timestamp(record):

# Don't modify the original! Return a new copy.

new_record = record.copy()

new_record['processed_at'] = datetime.datetime.now()

return new_record

product_updates = [

{'id': 101, 'price': 50.00},

{'id': 102, 'price': 120.50},

{'id': 103, 'price': 75.25}

]

processed_data = map(add_timestamp, product_updates)

print(list(processed_data))[{'id': 101, 'price': 50.0, 'processed_at': datetime.datetime(2025, 11, 11, 13, 40, 25, 123456)},

{'id': 102, 'price': 120.5, 'processed_at': datetime.datetime(2025, 11, 11, 13, 40, 25, 123457)},

{'id': 103, 'price': 75.25, 'processed_at': datetime.datetime(2025, 11, 11, 13, 40, 25, 123458)}]This pattern is ideal for batch updates and really shows the value of knowing your way around dictionaries.

Generating HTML elements

For web developers, map() can be a simple template engine. You can transform a list of data items into a list of HTML strings, ready to be rendered. Below is an example of how to transform a Python list into an unordered HTML list:

def create_list_item(text):

return f"<li>{text}</li>"

menu_items = ['Home', 'About', 'Contact']

# Map the function to the list

html_items = map(create_list_item, menu_items)

# Join the results into a single string

html_list = "\n".join(html_items)

print(f"<ul>\n{html_list}\n</ul>")<ul>

<li>Home</li>

<li>About</li>

<li>Contact</li>

</ul>Advanced Python map() Applications

While map() is excellent for simple, one-to-one transformations, its true power shows in more complex scenarios. Let's look at some advanced patterns where map() is a key component of a sophisticated data processing strategy.

Multi-iterable processing

We've touched on using map() with multiple iterables, and it is a pattern that is fundamental to many advanced data and scientific computations. When you provide multiple iterables, map() acts like a zipper, feeding the i-th element from each iterable to your function, meaning the number of arguments must match the number of iterables.

For example, to calculate the total value of different products in an inventory, you might have three separate lists. Let’s see how map() is used here:

product_ids = ['A-101', 'B-202', 'C-303']

quantities = [50, 75, 30]

prices = [10.99, 5.49, 20.00]

# A function that takes three arguments

def calculate_line_total(pid, qty, price):

# Returns a tuple of (id, total_value)

return (pid, round(qty * price, 2))

# map() feeds one element from each list into the function

line_totals = map(calculate_line_total, product_ids, quantities, prices)

print(list(line_totals))[('A-101', 549.5), ('B-202', 411.75), ('C-303', 600.0)]As noted before, map() stops at the shortest iterable. This is a deliberate feature to prevent IndexError exceptions. If your logic requires processing all items from the longest list (e.g., filling in defaults), remember to use itertools.zip_longest() instead. You can learn it alongside many other useful functions in this course on writing efficient Python code.

itertools.starmap() for nested iterables

What happens when your data is already "zipped" into a list of tuples? This is extremely common when working with database query results, CSV files, or coordinate pairs.

Suppose you have a list of (x,y) points as shown below, and you want to calculate the product of each pair.

points = [(1, 5), (3, 9), (4, -2)]You could use a lambda with map(), but it's a bit awkward with long nested functions within it:

list(map(lambda p: p[0] * p[1], points))A much cleaner, more Pythonic solution is itertools.starmap(). It takes a function and a single iterable of iterables (like our list of tuples). It then unpacks each inner tuple as arguments for the function. Let’s see this in action:

import itertools

points = [(1, 5), (3, 9), (4, -2)]

# A simple function that takes two arguments

def product(x, y):

return x * y

# starmap() unpacks each tuple from 'points' into (x, y)

# and passes them to product()

products = itertools.starmap(product, points)

print(list(products))[5, 27, -8]starmap() is the correct tool when your function's arguments are already pre-packaged in tuples. This pattern is especially useful when processing geospatial data, such as a list of (latitude, longitude) coordinates. For a deeper look into these concepts, I recommend taking this course on working with geospatial data in Python.

Functional programming integration

The map() function is very useful in functional programming. We can combine it with other functional tools like filter() and functools.reduce() to build clean, highly efficient data processing pipelines.

We've already seen the combination of filter() and map(). Now, let's see how to use reduce(), which aggregates (or "reduces") an iterable to a single cumulative value.

Let’s say you want to find the sum of the squares of all odd numbers in a given list. We can do that as follows:

from functools import reduce

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

# 1. Filter: Get only the odd numbers

odd_numbers = filter(lambda x: x % 2 != 0, numbers)

# -> Iterator(1, 3, 5, 7)

# 2. Map: Square the odd numbers

squared_odds = map(lambda x: x * x, odd_numbers)

# -> Iterator(1, 9, 25, 49)

# 3. Reduce: Sum the results

# (lambda a, b: a + b) is the summing function

# 'a' is the accumulator, 'b' is the next item

total = reduce(lambda acc, val: acc + val, squared_odds)

print(total)84This is a powerful pattern. Because map() and filter() both return lazy iterators, this entire operation is incredibly memory-efficient. No large, intermediate lists are ever created in memory. The data flows through the pipeline, item by item.

Lazy Evaluation and Memory Management

One of the most critical features of map() in Python 3 is its use of lazy evaluation. Understanding this concept is necessary for writing efficient, scalable code, especially for data practitioners who regularly handle large datasets. In this section, we’ll see how this works.

Benefits of lazy evaluation

In Python 3, map() does not immediately run your function and return a list. Instead, it returns a map object, which is an iterator. This iterator "knows" what function and what data to use, but it doesn't actually perform the calculation until you explicitly ask for the next item.

This "just-in-time" computation has profound benefits, like:

-

Memory Efficiency: A

mapobject occupies only a small, constant amount of memory, regardless of whether it's processing 10 items or 10 billion. It doesn't create a new list in memory to hold all the results. -

Performance with Large Datasets: When you iterate over the

mapobject (e.g., in aforloop), it computes and yields one value at a time. This allows you to process massive files or data streams that would be too large to fit in memory all at once. -

Chainability: As we saw in the functional programming section, lazy iterators can be chained together (e.g.,

map()afterfilter()). Because no intermediate lists are created, the data flows through the pipeline one item at a time, which is incredibly efficient.

Compare this to a list comprehension, which uses eager evaluation. Consider this example:

squared = [x * x for x in range(10000000)]This code will instantly try to create a list with 10 million numbers, potentially consuming a huge amount of RAM.

Using generator expressions

A generator expression is the lazy equivalent of a list comprehension. It looks very similar, but behaves like map() in terms of memory.

squared = (x * x for x in range(10000000))The code above also creates a memory-efficient iterator, just like map() would. The choice between map() and a generator expression often comes down to readability. map() can be clearer when applying a complex, existing function, while a generator expression is often more readable for simple, inline expressions.

Let’s compare the memory usage for these operations:

import tracemalloc

# Define the base data for comparison

large_numbers = range(10000000)

print("--- Memory Usage (Object Creation vs. List Materialization) ---")

# --- 1. Memory for List Comprehension (creates full list immediately) ---

tracemalloc.start()

list_comp_obj = [x * x for x in large_numbers]

current, peak = tracemalloc.get_traced_memory()

tracemalloc.stop()

print(f"Peak RAM for List Comprehension (full list): {peak / (1024 * 1024):.2f} MB")

del list_comp_obj # Free up memory

# --- 2. Memory for Map Object (lazy) ---

tracemalloc.start()

map_obj = map(lambda x: x * x, large_numbers)

current, peak = tracemalloc.get_traced_memory()

tracemalloc.stop()

print(f"Peak RAM for Map Object (iterator itself): {peak / (1024 * 1024):.2f} MB")

del map_obj # Free up memory

# --- 3. Memory for Generator Expression (lazy) ---

tracemalloc.start()

gen_exp_obj = (x * x for x in large_numbers)

current, peak = tracemalloc.get_traced_memory()

tracemalloc.stop()

print(f"Peak RAM for Generator Expression (iterator itself): {peak / (1024 * 1024):.2f} MB")

del gen_exp_obj # Free up memory--- Memory Usage (Object Creation vs. List Materialization) ---

Peak RAM for List Comprehension (full list): 390.16 MB

Peak RAM for Map Object (iterator itself): 0.03 MB

Peak RAM for Generator Expression (iterator itself): 0.03 MBNote: The 'Peak RAM' for Map/Generator Objects here refers to the memory allocated to the iterator object itself, not the memory of the full list it would produce if converted, demonstrating their lazy nature.

Converting map objects to iterables

Since map() returns a lazy iterator, you often need to materialize it or convert it into a concrete collection to actually use the results.

You should convert a map object when you need to:

-

See all results at once (e.g., to

print()them). -

Access elements by index (e.g.,

results[0]). -

Get the length of the results (e.g.,

len(results)). -

Pass the results to a function that requires a list or set.

-

Iterate over the results multiple times. (A

mapobject, like all iterators, is exhaustible.) You can only loop over it once.

Here’s how to convert a map object:

def square(x):

return x * x

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 3, 4, 5]

map_obj = map(square, numbers)

# --- Common Conversions ---

# 1. To a list:

list_results = list(map_obj)

print(f"List: {list_results}")

# Important

# The map_obj is now exhausted.

# If you try to do list(map_obj) again, you'll get an empty list.

# You must re-create the map object to reuse it.

map_obj = map(square, numbers) # Re-create it

# 2. To a set (removes duplicates):

set_results = set(map_obj)

print(f"Set: {set_results}")

map_obj = map(square, numbers) # Re-create it

# 3. To a tuple:

tuple_results = tuple(map_obj)

print(f"Tuple: {tuple_results}")List: [1, 4, 9, 9, 16, 25]

Set: {1, 4, 9, 16, 25}

Tuple: (1, 4, 9, 9, 16, 25)To convert to a dictionary (if the output is key-value pairs), you might use map() with dict(), but often Python's dictionary comprehensions are clearer.

The key takeaway is to be intentional. Let map() remain a lazy iterator as long as possible in your pipeline, and only convert it to a list at the very last moment when you actually need concrete results.

Become a ML Scientist

Handling Errors and Edge Cases in map()

While map() is highly efficient, it can lead to unexpected behavior or errors if not used with care. We need to understand these common pitfalls, especially concerning mutability and types. Let’s see some edge cases and how to handle errors.

Handling mutable state

A common mistake is using map() with a function that mutates (changes in place) its input, especially when that input is a mutable object like a list or dictionary.

The map() function is designed for transformations, not for in-place side effects. While it's technically possible to mutate objects inside the function passed to map(), this is considered bad practice for several reasons:

-

It's confusing and not very Pythonic (it goes against the functional programming style).

-

Because

map()is lazy in Python 3, the mutation doesn't happen until the map object is consumed (e.g., by converting to a list or iterating over it). -

It's far less explicit than a simple

forloop.

map() side effects

Using map() for side effects is considered bad practice. Let’s see why:

def add_bonus(employee_dict):

# This function MUTATES the dictionary

employee_dict['salary'] *= 1.10

return employee_dict

employees = [

{'name': 'Alice', 'salary': 100000},

{'name': 'Bob', 'salary': 120000}

]

map(add_bonus, employees)

print(employees)[{'name': 'Alice', 'salary': 100000}, {'name': 'Bob', 'salary': 120000}]We can see the output; nothing has changed yet, as map() is lazy. The update only happens when you wrap it into list():

list(map(add_bonus, employees))

print(employees)[{'name': 'Alice', 'salary': 110000.00000000001}, {'name': 'Bob', 'salary': 132000.0}]This behavior is confusing and can lead to unpleasant surprises. If your goal is to mutate in place, a simple for loop is much clearer, as shown below:

for emp in employees:

emp['salary'] *= 1.10

employees[{'name': 'Alice', 'salary': 110000.00000000001},

{'name': 'Bob', 'salary': 132000.0}]Best practice to avoid errors using map()

For map(), this means using it only for pure transformations to return new objects, not to change old ones. Let’s see the above example using map():

def calculate_bonus(employee_dict):

new_record = employee_dict.copy() # Or use dict(employee_dict)

new_record['salary'] *= 1.10

return new_record

employees = [

{'name': 'Alice', 'salary': 100000},

{'name': 'Bob', 'salary': 120000}

]

updated_employees = list(map(calculate_bonus, employees))

print("--- Original ---")

print(employees) # The original data is safe

print("--- Updated ---")

print(updated_employees)--- Original ---

[{'name': 'Alice', 'salary': 100000}, {'name': 'Bob', 'salary': 120000}]

--- Updated ---

[{'name': 'Alice', 'salary': 110000.0}, {'name': 'Bob', 'salary': 132000.0}]Some rules of thumb:

-

Use

map()when you want to have new data (pure functions, immutable style). -

Use a

forloop (or list comprehension) when you intentionally want to mutate in place. -

Avoid relying on side effects in

map()as it leads to subtle, hard-to-debug issues.

Type constraints and common pitfalls

The most common errors with map() are TypeError exceptions. They almost always fall into one of the three following categories.

The function is not callable

When you pass something to map() as the first argument that isn't a function, method, or lambda, you will receive a TypeError.

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

message = "Not a function"

# This will fail

try:

list(map(message, my_list))

except TypeError as e:

print(e)'str' object is not callableThe argument is not iterable

The same thing happens when you pass something as the second argument (or any subsequent iterable) that Python can't loop over, like a single number or a boolean.

def square(x):

return x * x

# This will fail

try:

list(map(square, 12345))

except TypeError as e:

print(e)'int' object is not iterableArgument count mismatch when using multiple iterables

When you give map() more than one iterable, it pulls one item from each iterable on every call. Your function must accept exactly that many arguments; otherwise, it will lead to a TypeError as well.

list_a = [1, 2, 3]

list_b = [4, 5, 6]

# Wrong: lambda only accepts one argument

try:

list(map(lambda x: x * x, list_a, list_b))

except TypeError as e:

print(e)<lambda>() takes 1 positional argument but 2 were givenTo debug these issues:

-

Check the first argument: Is it definitely a function name without parentheses (like

square, notsquare()), a lambda, or a built-in method (likestr.strip)? -

Check the second argument: Is it definitely a list, tuple, set, string, or other collection?

-

Check argument mismatch: If using multiple iterables, does your function accept the correct number of arguments?

Optimizing Performance with Python map()

While map()'s lazy evaluation already provides significant memory benefits, you can further optimize its speed and efficiency. These strategies are useful while working with performance-critical data pipelines. Let’s see some of these performance strategies and benchmarks.

map() best practices

We can improve the performance gains of the map() function by using the following methods:

Prefer built-in functions

Whenever possible, use built-in functions (like len(), str.strip(), str.upper()) directly as the mapping function instead of wrapping them in a lambda. Built-in functions are highly optimized (often implemented in C) and will almost always be faster than equivalent lambda or user-defined Python functions.

-

Faster:

map(str.upper, my_list) -

Slower:

map(lambda s: s.upper(), my_list)

Leverage itertools

The itertools module is your best friend for high-performance iteration. Functions like itertools.starmap() or itertools.islice() are designed to work with map objects and maintain memory efficiency when lazily slicing an iterator. Chaining itertools functions is very useful in data processing.

Avoid unnecessary list conversions

This is the most important rule. Calling list(map(...)) forces the entire operation to execute immediately and loads all results into memory. Avoid this conversion inside loops or intermediate steps. Keep your data as an iterator for as long as possible, and only convert to a list when you absolutely need the final, concrete collection.

Performance benchmarks

Let's look at the impact of these choices using some benchmarks.

When you call map(lambda x: len(x), data), Python has to invoke the lambda function for each item, which then, in turn, calls the built-in len(). This extra layer of function call overhead adds up.

When you use map(len, data), map() can call the highly optimized len() function directly for each item.

Here's a simple benchmark using timeit:

import timeit

data = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry'] * 100000

# Benchmark 1: Using lambda

time_lambda = timeit.timeit(

'list(map(lambda s: len(s), data))',

globals=globals(),

number=100

)

# Benchmark 2: Using built-in

time_builtin = timeit.timeit(

'list(map(len, data))',

globals=globals(),

number=100

)

print(f"Time with lambda: {time_lambda:.4f}s")

print(f"Time with built-in: {time_builtin:.4f}s")

# The built-in will be significantly fasterTime with lambda: 2.5304s

Time with built-in: 0.5363sThe speed benchmark above forced a list() conversion. However, the primary performance benefit of map() is memory efficiency. Consider processing a 5GB log file line by line.

-

List comprehension: Since it will attempt to read the entire 5GB file and store the millions of processed results in RAM, it will likely cause a

MemoryError. -

map()function: Creates only a tinymapobject. When you iterate over it (e.g.,for r in results:), it reads one line from the file, processes it, yields the result, and then reads the next line. At no point is the result of more than one line held in memory.

This lazy-loading behavior is what makes map() a superior choice for large-scale data processing, especially in frameworks like PySpark, where data might not even live on one machine. For a quick, deep look at large-scale data tools like PySpark, go through the PySpark cheat sheet.

map() vs. List Comprehensions and Alternatives

No doubt, the map() function is a powerful tool. However, it's not the only way to apply an operation across an iterable. Choosing the right tool for the job, whether it's a map(), a list comprehension, or a generator expression, is important to writing clean, efficient, and Pythonic code.

Let’s summarize the differences we have discovered throughout the tutorial:

|

Method |

Syntax Example |

Evaluation |

Memory Usage |

Best For… |

|

map() |

list(map(func, data)) |

Lazy (until consumed) |

Low (iterator) |

Applying an existing, named function to an iterable. |

|

List Comprehension |

[func(x) for x in data] |

Eager (immediate) |

High (creates new lis t) |

Simple transformations, filtering, and creating new lists. |

|

Generator Expression |

(func(x) for x in data) |

Lazy (until consumed) |

Low (iterator) |

Simple transformations, memory-efficient pipelines. |

|

itertools.starmap() |

list(starmap(func, data)) |

Lazy (until consumed) |

Low (iterator) |

Applying a function to an iterable of iterables (e.g., a list of tuples). |

When to choose map() vs. list comprehensions

The main difference between map() and a list comprehension is that the former evaluates lazily, while the latter uses lazy evaluation.

A list comprehension is often more readable for simple, inline expressions, but it immediately creates a new list, which can block precious memory space. map(), on the other hand, is memory-efficient, making it ideal for very large datasets where creating an intermediate list is not feasible.

When to choose map() vs. generator expressions

map() and generator expressions are very similar. Both evaluate lazily and are therefore memory-efficient.

When there is a pre-defined function, map(func, data) is often preferred, since it is a clear signal that you are "mapping" this function. Generator expressions, however, are often more readable for new or lambda-like expressions, as the syntax is self-contained.

When to choose map() vs. itertools.starmap()

starmap() is the specialized version of map() designed specifically for an iterable of tuples (or other iterables). This creates a clear distinction between the two: use map() for independent, parallel iterables, and starmap() when your arguments are already grouped together.

It automatically unpacks each inner tuple as separate arguments to the function, so instead of writing map(lambda args: func(*args), data), you can simply write starmap(func, data). This makes the code much cleaner and more readable whenever your data is already grouped into tuples.

map() readability comparison

Readability is a major factor in Python. While performance is critical for large datasets, clear code is easier to maintain and debug. Let’s take a look at how syntax and readability vary among these functions using a simple code example of squaring the values in a list:

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]

# --- 1. map() with lambda ---

# Functional, but a bit verbose

squared_map = list(map(lambda x: x * x, numbers))

# --- 2. List Comprehension ---

# Widely considered the most Pythonic and readable for this case

squared_list_comp = [x * x for x in numbers]

# --- 3. Generator Expression ---

# Identical to list comp., but lazy.

# Requires a list() call to print.

squared_gen_exp = list((x * x for x in numbers))

# --- 4. map() with a named function ---

# Very readable if the logic is complex

def square(x):

return x * x

squared_map_func = list(map(square, numbers))All four approaches yield [1, 4, 9, 16].

If you insist on when to choose what, here’s my recommendation:

-

For simple expressions and creating a new list, use a list comprehension. It’s concise, readable, and the community standard.

-

For applying an existing function, use

map(). In many cases, it looks cleaner than list comprehensions, though some style guides disagree. -

For large datasets where memory matters, use

map()without immediately callinglist()on it or a generator expression. Both are lazy. Choosemap()when reusing an existing function, and generator expressions when the logic is in-line. -

For complex logic (multiple statements, conditionals, etc.), define a properly named function with def and use

map()(or just a regular for loop). This is far more readable, debuggable, and testable than a complex lambda or a multi-line comprehension.

Conclusion

Python's map() function is a powerful tool for efficient data transformation. Its key feature is lazy evaluation, which allows it to return an iterator and process items on demand. This makes it extremely memory-efficient for large datasets, unlike list comprehensions, which build a new list in memory.

Just remember that because it produces an iterator, you must convert the result into a concrete collection, such as a list or tuple, if you need to access the values immediately or use them multiple times.

Looking ahead, the use of functional patterns in Python is becoming increasingly sophisticated. A significant area for development is the integration of map() with Python’s type-hinting system. Mastering how to apply precise type definitions to complex map() transformations will be essential for writing robust, future-proof code.

If you want to build upon the new knowledge and learn to become a real Python pro, make sure to enroll in the Python programming skill track.

Python map() FAQs

How does the map() function compare to list comprehensions in terms of performance?

map() is more memory-efficient due to lazy evaluation, while list comprehensions are eager and create the entire list in memory at once.

Can you provide examples of using map() with multiple iterables?

For example, list(map(lambda x, y: x + y, [1, 2], [10, 20])) adds elements from two lists, resulting in [11, 22].

What are the advantages of using map() over for loops?

map() is more concise, fits a functional programming style, and is highly memory-efficient as it returns a lazy iterator.

How does lazy evaluation work with the map() function?

It returns an iterator that computes each item's new value only when you iterate over it, rather than computing all values up front.

Are there any common pitfalls to avoid when using map()?

Yes, common pitfalls include TypeError (from a non-callable function or non-iterable argument) and using functions with side effects (like mutating an object).

I am a data science content writer. I love creating content around AI/ML/DS topics. I also explore new AI tools and write about them.