Course

At some point, every Python program needs to save something: logs, results, user input, configuration files, or processed data. You might be exporting analysis results, recording what your script did, or persisting application state between runs. Whatever the case, writing to files is a core Python skill you’ll use again and again.

In this guide, you’ll learn how to write to files in Python using the standard library. We’ll start with the basics, then move through file modes, encodings, structured formats like JSON and CSV, and production-ready patterns that make your code safer and more predictable. By the end, you’ll be able to write files confidently in real applications not just toy examples.

If you’re already comfortable with Python basics, this tutorial helps bridge the gap between scripts and professional-grade file handling. If you want to reinforce the fundamentals as you go, our Introduction to Python and Intermediate Python courses pair well with this walkthrough.

Learn Python From Scratch

Getting Started: Your First File Write in Python

The fastest way to understand file writing in Python is to actually do it. Let’s start with the simplest possible example and build from there.

The basic pattern (step by step)

At its core, writing to a file follows a simple pattern:

- Open a file

- Write content to it

- Close the file

Python provides the built-in open() function to handle the first step.

The open() function, explained simply

The open() function connects your Python code to a file on disk. You tell it two things:

- Which file you want to work with

- How you want to work with it

For writing, the most common mode is "w", which means write. If the file doesn’t exist, Python creates it. If it does exist, Python overwrites it.

file = open("example.txt", "w")

file.write("Hello, world!")

file.close()Run this script, and Python creates a file called example.txt in the same directory as your code.

So what just happened?

-

open("example.txt", "w")opens or creates the file -

write()sends text into the file -

close()flushes the data and releases the file

This works, but it’s not how you should write files long-term.

The Right Way in Python: Using Context Managers

Manually opening and closing files is easy to forget and easy to get wrong. That’s why Python encourages using context managers.

Here's why using with is better: Using with ensures the file is always closed properly, even if something goes wrong while writing. It makes your code safer and easier to read.

with open("example.txt", "w") as file:

file.write("Hello, world!")Once the with block ends, Python automatically closes the file. This pattern shows up everywhere in professional Python code and is worth committing to memory. You’ll see it repeatedly in our Python Programming skill track and our Writing Clean Python Code course.

A Python Write to File Example

Let’s apply this to something slightly more realistic. Here I'm going to create a daily journal entry.

from datetime import date

today = date.today().isoformat()

with open("journal.txt", "a", encoding="utf-8") as file:

file.write(f"{today}: Practiced writing files in Python.\n")This introduces two important ideas:

-

Append mode (

"a") -

Writing structured, repeatable entries

-

Each run adds a new line without deleting earlier entries.

Understanding File Modes: When to Use w, a, x, and r+

Once you know how to write to a file, the most important decision becomes how you open it. File modes control whether data is overwritten, preserved, or protected.

Write mode (w): Starting fresh

Write mode creates a file if it doesn’t exist. It also overwrites it if it does.

with open("report.txt", "w") as file:

file.write("Daily sales report\n")Use this when you want a clean slate. Be careful because this mode deletes existing data silently.

Append mode (a): Adding without losing data

Append mode adds content to the end of a file.

with open("activity.log", "a") as file:

file.write("User logged in\n")This is ideal for logs and incremental records and is one of the safest modes for production systems.

Exclusive mode (x): Safe file creation

Exclusive mode creates a file only if it doesn’t already exist.

try:

with open("config.txt", "x") as file:

file.write("initialized=true")

except FileExistsError:

print("File already exists.")This is useful for setup scripts where overwriting would be risky.

Read-write mode (r+): Modifying existing files

This mode allows reading and writing but requires the file to exist.

with open("notes.txt", "r+") as file:

content = file.read()

file.write("\nNew note added.")Writing happens at the current file pointer position, which is why understanding cursor movement matters here.

So which mode should you use? Here's my mental guide:

-

Overwrite existing data →

w -

Keep data and add more →

a -

Prevent overwrites →

x -

Read and update the same file →

r+

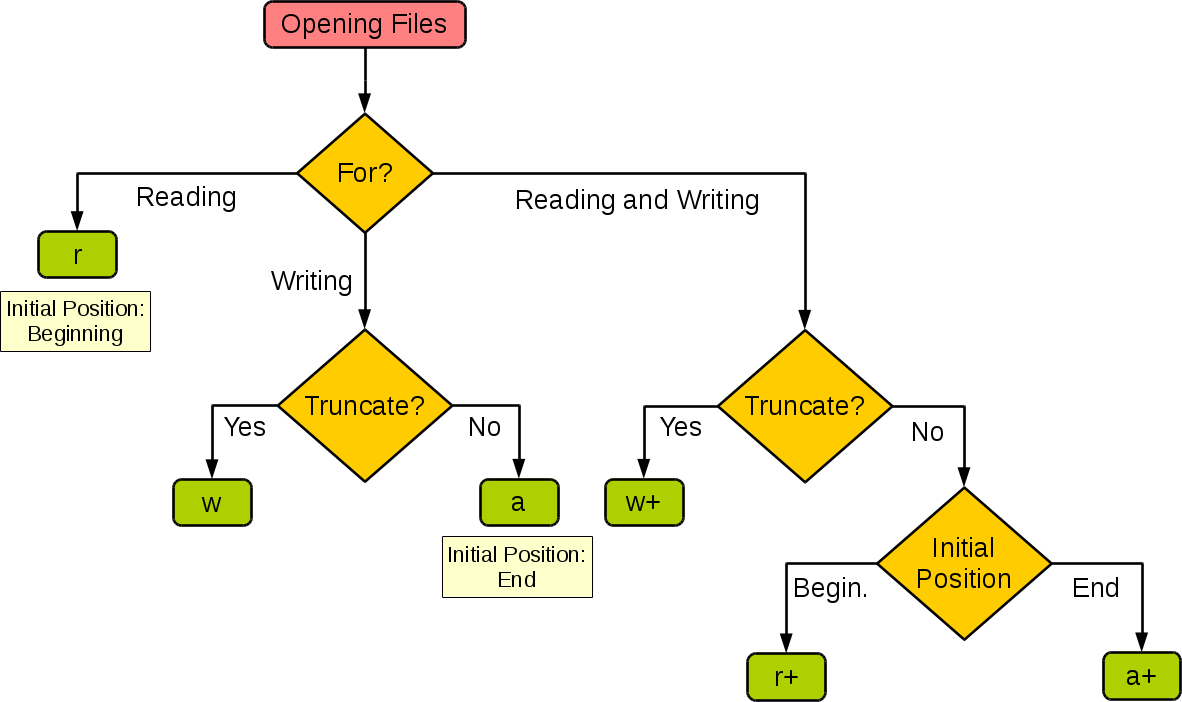

To reinforce this decision process visually:

Choosing the right file mode usually comes down to intent: overwrite, append, protect, or modify.

Writing Different Types of Content in Python

Once you’re comfortable opening files with the right mode, the next question is what you’re actually writing.

In real programs, you’re not always writing a single string. You might be saving lists, exporting results, or working with non-text data like images or PDFs.In this section, you’ll learn how to write different kinds of content to files safely and efficiently.

Writing text and strings

The simplest case is writing plain text. Python gives you two main methods for this: write() and writelines().

write() writes exactly what you pass, no automatic newlines.

with open("example.txt", "w") as file:

file.write("First line\n")

file.write("Second line\n")write() vs. writelines()

The key difference is simple write() writes one string at a time while writelines() writes a sequence of strings as-is; writelines() does not add newlines for you, so each element must already end with \n.

In practice, many developers still prefer write() in a loop because it’s easier to read.

lines = ["One\n", "Two\n", "Three\n"]

with open("example.txt", "w") as file:

file.writelines(lines)Writing lists efficiently

items = ["apple", "banana", "cherry"]

content = "\n".join(items)

with open("fruits.txt", "w") as file:

file.write(content)Joining first reduces repeated disk writes, which matters for larger datasets.

Writing binary data

Binary mode ("wb") is required for non-text files.

binary_data = b"\x89PNG\r\n\x1a\n"

with open("image.bin", "wb") as file:

file.write(binary_data)Working with Encodings in Python (Why Your Text Looks Broken)

Encoding issues are one of the most common—and frustrating—file-handling bugs.

Always specify UTF-8

Explicit encoding prevents cross-platform issues and corrupted characters, as you can see here:

with open("example.txt", "w", encoding="utf-8") as file:

file.write("Café, résumé, naïve")Real-world example: Multilingual text

Being explicit here saves hours of debugging later. Here’s what I mean:

customers = ["Ana García", "François Dupont", "Miyuki 山田"]

with open("customers.txt", "w", encoding="utf-8") as file:

for name in customers:

file.write(name + "\n")Advanced Python Writing Techniques

Once you’re comfortable writing files in Python, the next set of problems usually isn’t how to write but how to do it safely and efficiently. Large files, unexpected crashes, and performance bottlenecks all introduce edge cases that we haven't covered yet.

Handling large files with chunked writes

Streaming output keeps memory usage low:

def generate_lines():

for i in range(1_000_000):

yield f"Line {i}\n"

with open("large.txt", "w", encoding="utf-8") as file:

for line in generate_lines():

file.write(line)Atomic writes: Preventing corruption

The idea here is to prevent partial writes if a program crashes mid-update.

import os, tempfile

def atomic_write(path, content):

with tempfile.NamedTemporaryFile("w", delete=False) as tmp:

tmp.write(content)

os.replace(tmp.name, path)Beyond Text Files: Writing JSON and CSV

Once your data has structure, plain text stops being the best option. Python makes it easy to write common structured formats like JSON and CSV, so you can store data in a way that’s easier to share, inspect, and process later.

Writing JSON

When you’re working with dictionaries or nested data, JSON is usually the most natural format to write to. Python’s built-in json module handles the conversion for you, so you don’t need to manually format strings.

import json

data = {"id": 1, "name": "Jeremiah"}

with open("user.json", "w", encoding="utf-8") as file:

json.dump(data, file, indent=2)Writing CSV

If your data is tabular and likely to be opened in spreadsheets or BI tools, CSV is a better fit. The csv module helps you write rows safely without worrying about delimiters or quoting.

import csv

rows = [{"id": 1, "name": "Alice"}, {"id": 2, "name": "Bob"}]

with open("users.csv", "w", newline="", encoding="utf-8") as file:

writer = csv.DictWriter(file, fieldnames=["id", "name"])

writer.writeheader()

writer.writerows(rows)Common Python Write to File Mistakes

Even though writing files in Python is straightforward, a few small mistakes tend to cause most real-world issues. These problems usually aren’t about syntax; they come from overlooked details like resource management, file modes, or performance choices.

Keep the following points in mind.

-

Forgetting to close files → use

‘with’ -

Overwriting data unintentionally → double-check modes

-

Ignoring encoding → always specify UTF-8

-

Writing large files inefficiently → batch or stream output

Most bugs here come from small oversights, not complex logic.

Conclusion

Writing to files in Python starts simple, but real-world programs demand more care. In this guide, you moved from your first file write to choosing safe file modes, handling encodings correctly, exporting structured data, and applying production-ready patterns.

The key takeaway is intent: choose the right mode, be explicit about encoding, and write defensively when data matters.

Become a Python Developer

Tech writer specializing in AI, ML, and data science, making complex ideas clear and accessible.

FAQs

Can Python write files asynchronously?

Yes, with libraries like aiofiles, though most scripts don’t need it.

What’s the safest write mode?

Append ("a") or exclusive ("x") depending on intent.

Why is my text corrupted?

Encoding mismatch—always use UTF-8.

Where is my file being saved?

Relative to the script’s working directory.

Should I use pathlib?

Yes, for cleaner, cross-platform path handling.