Track

Synchronizing local repositories with their remote counterparts is a fundamental aspect of working with Git.

Two commonly confused commands in accessing code remotely are git fetch and git pull. While they appear similar, their differences have meaningful implications for code review, branch management, and overall team productivity.

In this article, we'll cover what each of the functions does, look at some examples, and as well as some best practices for using them. If you’re still learning about Git, I recommend checking out our Git Fundamentals skill track.

Key Differences Between Git Fetch and Git Pull

Though related, the commands differ in both behavior and intent.

Let’s compare them in a table below:

|

Differences |

Git Fetch |

Git Pull |

|

Purpose |

Updates remote-tracking branches only |

Updates remote-tracking branches and integrates into the current branch |

|

Effect on working directory |

No changes to files |

Changes applied immediately to files in working branch |

|

Safety |

Safe; changes are not merged automatically |

Less safe; can trigger merge conflicts right away |

|

Control |

Gives user full control over when and how to merge |

Automates integration; less manual decision-making |

|

History impact |

Keeps history clean until merge is done |

May add merge commits (with merge) or rewrite your local commit history (with rebase) |

|

Common use cases |

Code review, planning integration, safe syncing |

Fast updates, CI/CD pipelines, trusted environments |

As you can see, the commands differ in both behavior and intent:

git fetchupdates only remote-tracking references, leaving your working branch untouched.git pullupdates remote-tracking references and integrates them into your current branch immediately.

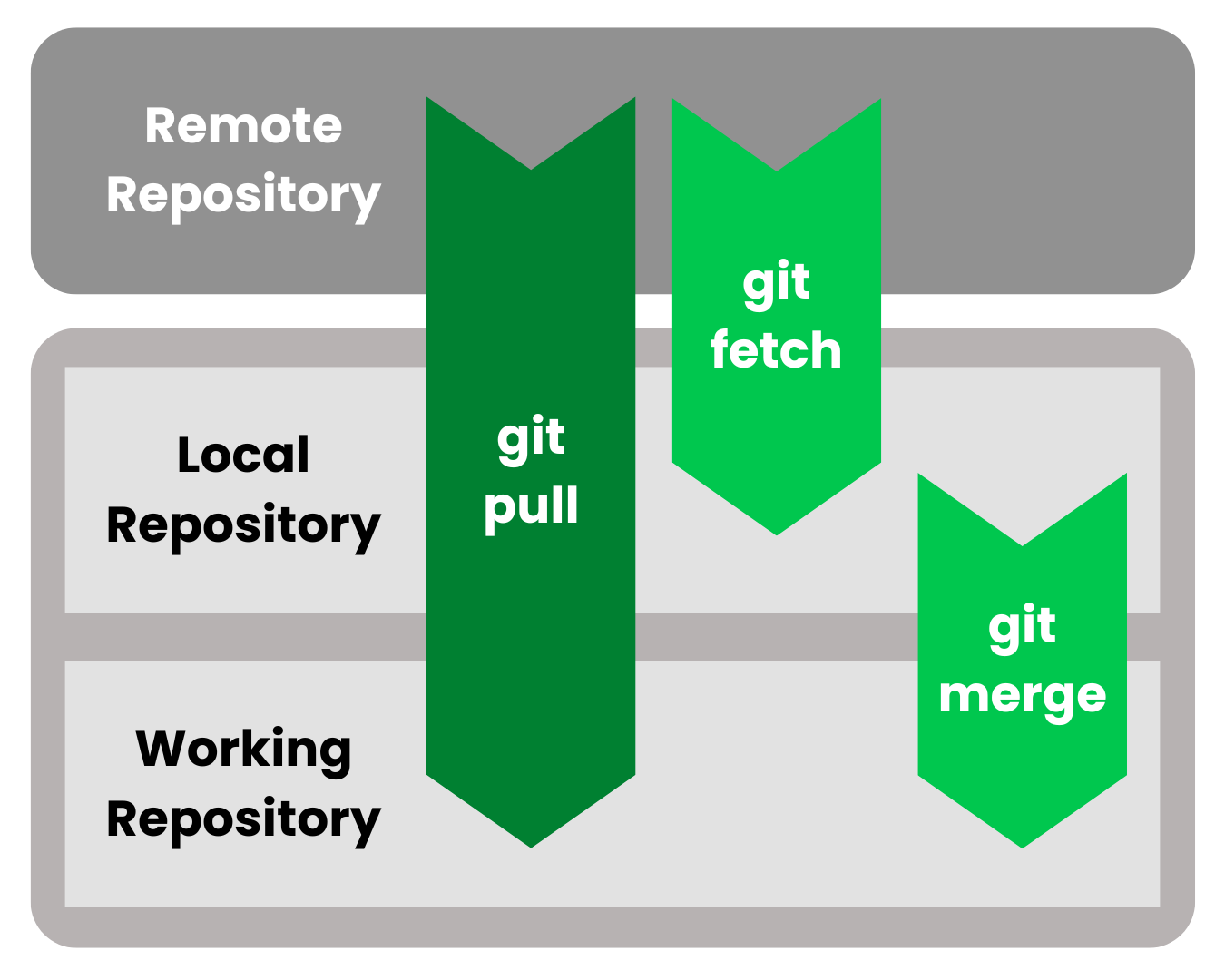

Visual Guide: How Git Fetch and Pull Works

As shown in the visual flow above, the differences between fetch and pull are in terms of where your code flows to.

In summary:

- Fetch: Remote commits move into remote-tracking branches (

origin/main). Your localmainremains unchanged, giving you visibility into updates without disruption. - Pull: Remote commits move into remote-tracking branches and then merge or rebase into your local branch, shifting your branch pointer immediately.

Overview of Git Repository Architecture

To fully appreciate git fetch and git pull, we'll have to understand Git’s internal structure and the layers at play.

Git is fundamentally a distributed version control system, which means every developer has a full copy of the repository including history, branches, and tags.

This architecture allows work to continue independently of a central server, making commands like fetch and pull the bridges that keep distributed environments in sync.

Git repositories operate in multiple layers:

- Working directory: The actual files you see and edit. This is where you write code, edit text, and run builds. Changes here are untracked until explicitly staged.

- Staging area (Index): A buffer zone where you prepare a curated set of changes to commit. This allows fine-grained control over what becomes part of a project’s history.

- Local repository: The

.gitdirectory that holds the database of all commits, branches, tags, and configuration. This is entirely local and doesn’t change unless you commit or explicitly sync. - Remote repository: Hosted elsewhere (e.g., GitHub, GitLab, Bitbucket), serving as the collaboration hub for multiple developers. It’s the common ground where teams share progress.

These layers function independently, meaning that syncing with a remote doesn’t immediately affect your working directory.

Instead, changes propagate gradually in this order:

remote → remote-tracking branches → local repository → working directory.

Remote tracking branches

Remote-tracking branches are special references that represent the state of branches in the remote repository.

For example, origin/main tells you where the main branch on the origin remote was the last time you fetched.

They act as bookmarks, enabling you to:

- Compare your branch against the remote version.

- See what commits are pending for integration.

- Safely track remote progress without changing your current code.

- When you run

git fetch, Git updates these remote-tracking branches. - When you merge or rebase, you move the changes from those remote-tracking references into your local branch.

This separation means you can observe and analyze updates before they affect your actual development work. You can learn more in our Git remote tutorial.

What Is Git Fetch?

git fetch retrieves commits, branches, and tags from a remote repository and updates your remote-tracking branches without altering your current branch or working files.

Try to think of it as “downloading the latest map of the remote repository” without stepping into the new territory.

It is especially useful for developers who want visibility into remote activity without risking unintended changes to their own work.

Syntax and usage

The command is used in the bash terminal or command line interface (CLI). Here are some syntax details you should take note of:

Common fetch commands:

# Fetch all remotes

git fetch --all

# Fetch only one branch

git fetch origin main

# Fetch and prune stale references

git fetch --prune

# Fetch a specific tag

git fetch origin tag v1.2.0Here's an explanation for each command and its respective options:

--allensures all configured remotes are updated, which is useful in multi-remote setups.- Fetching a single branch using

git fetch origin mainis efficient if you only care about one stream of work. --pruneremoves outdated remote-tracking branches that no longer exist on the server, keeping your environment clean.- Fetching tags using

git fetch origin tagis helpful in release workflows where tagged commits matter more than full branches.

Common use cases

Developers use git fetch in a variety of scenarios where visibility and control matter. For example:

- Code review: Use fetch to see what others have pushed before deciding to integrate.

- Planning integration: Compare changes in

origin/mainwith your local branch to prepare merging or rebasing. - Collaboration: Avoid disruptive auto-merges by fetching, reviewing, and merging on your terms.

- Experimentation: Developers often fetch updates into a separate branch to test new features without disturbing the mainline branch.

- Continuous monitoring: Teams may fetch regularly to keep local mirrors of the remote repository updated for reporting or analysis tools.

What Is Git Pull?

git pull is more aggressive than fetch because it both downloads changes and immediately attempts to integrate them into your current branch.

This means that the git pull command is a combination of both the git fetch and git merge commands.

By default, this integration is a merge, but it can be configured to use rebase. While convenient, this command assumes you want remote updates applied right away.

It is the go-to command for developers who prioritize speed and immediate synchronization.

Syntax and usage

Now, let's look at the syntax of using this command.

Here are some examples:

# Default fetch + merge

git pull origin main

# Fetch + rebase for cleaner history

git pull --rebase origin main

# Pull all changes from default remote

git pull

# Pull with fast-forward only (avoids merge commits)

git pull --ff-onlyHere's an explanation of the code above:

- With merge, you may get extra merge commits, which are explicit but sometimes noisy.

- With

--rebase, Git reapplies your local commits on top of the remote branch, creating a cleaner, linear history. - Using the

--ff-onlyoption ensures the branch is fast-forwarded without unnecessary merges, which is often desirable for clean workflows.

In Git, "fast-forwarding" refers to a specific type of merge operation that occurs when the branch you are merging into has not diverged from the branch you are merging from.

This means there are no new commits on the target branch (the one you are currently on) that are not also present in the source branch (the one you are merging).

In essence, fast-forwarding is a streamlined merge process that simplifies history when a linear progression of commits is maintained between branches.

Common use cases

This command can be used in a variety of cases to control development code, such as:

- Agile environments: Frequent integration ensures everyone works on the latest code.

- Continuous delivery pipelines: Automating pulls ensures deployment servers are always up to date.

- Trusted workflows: When remote updates are guaranteed stable and code reviews are already complete.

- Solo projects: Pull is faster when you’re the only contributor and don’t need to review others’ code.

Safety and control considerations

The git pull command can come with some concerns. Here are some safety aspects to consider:

- Pull provides convenience: everything happens in one step, but you give up some control.

- Error handling: Pull may introduce conflicts right away, while fetch allows you to prepare for them in advance.

- History clarity: Fetch-first workflows keep history cleaner and easier to audit, while pull can clutter history if used carelessly.

- Collaboration impact: Pulling too quickly can cause team members to unknowingly introduce unstable changes into shared branches.

When to Use Git Fetch vs Git Pull

Choosing between fetch and pull depends on workflow and project requirements.

- Use fetch when:

- You want to review before integrating.

- You’re working on high-stakes projects where stability matters.

- Your team values deliberate merges after code review.

- You want to keep a clean history without extra merges.

- Use pull when:

- Speed matters more than manual review.

- You’re working in smaller teams with high trust.

- CI/CD pipelines automatically resolve integration.

- You want to minimize manual steps in fast-moving projects.

Team collaboration considerations

Team culture and project type need to be considered when deciding on which approach to take.

In general, you can take on two different strategies.

- Fetch-first strategy: Encourages communication, code review, and careful merging. Best for open-source or enterprise projects with strict standards.

- Pull-first strategy: Maximizes agility and reduces time spent on manual merges. Best for startups or lean teams where speed is a higher priority than strict review.

Best Practices and Precautions

When working with the two commands, developers tend to have some best practices in place to prevent unexpected changes to code.

Here are some tips to consider:

- Commit before pull: Always save your work to avoid conflicts with uncommitted changes.

- Leverage rebase:

git pull --rebasehelps avoid cluttered histories. - Back up your branch: Create a safety branch before large pulls, especially in critical projects.

- Communicate with team: Ensure alignment on whether fetch-first or pull-first is the standard to avoid mismatches.

- Use descriptive commit messages: Especially when merge commits occur after a pull.

- Test after pull: Run local tests immediately after pulling to catch any broken code early.

Related Commands

Beyond just accessing remote repositories, Git can also be used for other purposes to ensure good version control.

Here are some common related commands:

git diff HEAD..origin/main: Compare local and remote.git branch -a: Inspect all branches, local and remote.git clone: The starting point for synchronization, it creates a copy of the remote repository on your local machine.

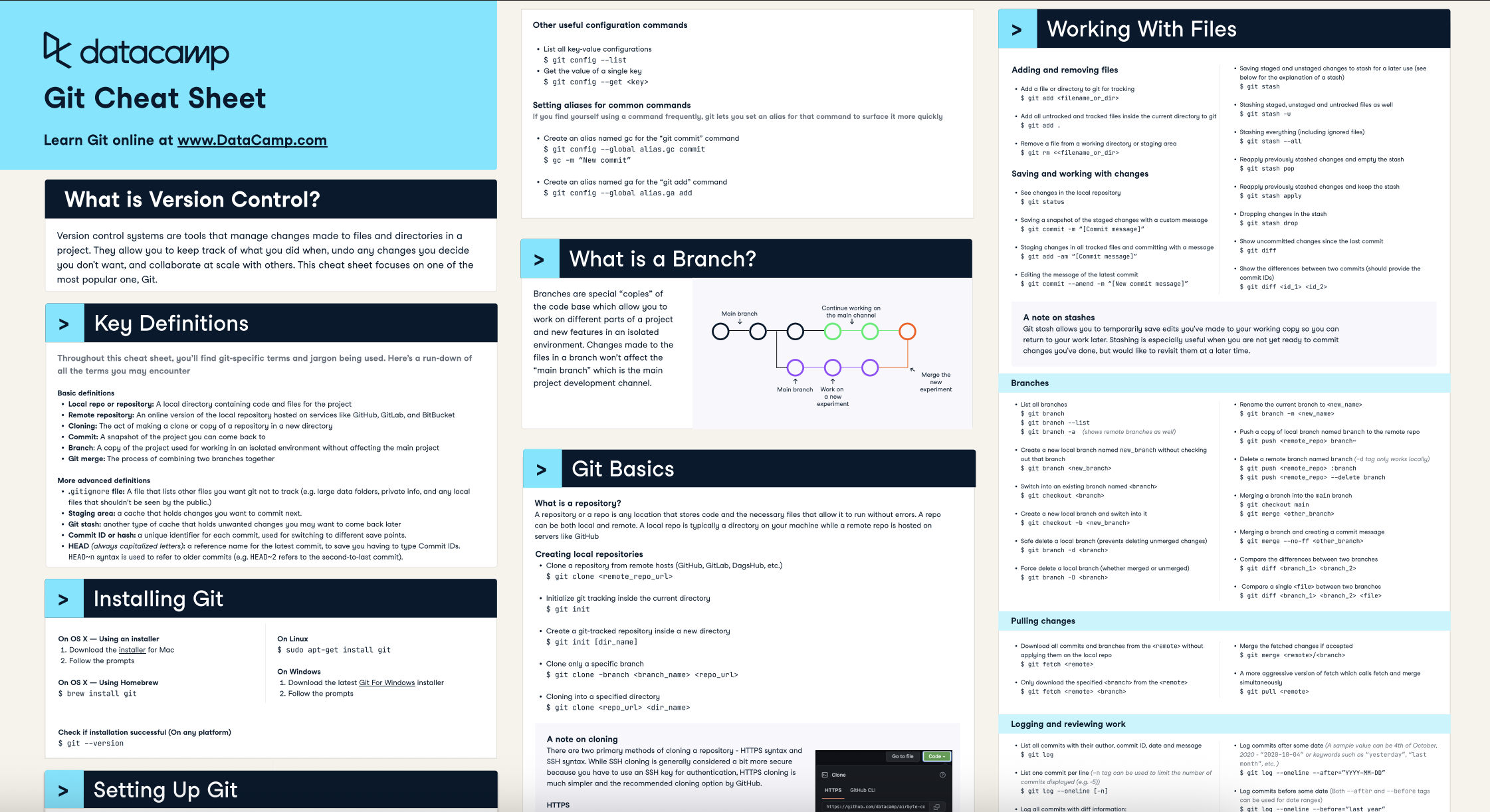

More on Git commands in the cheat sheet below.

Source: DataCamp Git Cheat Sheet

Automation and Scripting

In CI/CD environments, using fetch and pull is common.

Automation can be enabled through these examples:

- Fetch in build systems: Ensures systems test against the latest code without introducing changes automatically.

- Automating pulls with rebase: Keeps deployment histories consistent and prevents messy commit graphs.

- Post-fetch validation: Automatically run tests, linting, or security scans after syncing.

- Scheduled fetches: Some teams run regular fetch jobs to keep mirrors of repositories updated for reporting tools or auditing.

Practical Workflows and Use Cases

Git commands are powerful when used for managing development workflows.

As such, they can be used well in the following use cases:

- Feature branch workflow: Developers fetch to review remote changes before merging them into ongoing feature work, ensuring features are built on the latest foundation.

- Backup and recovery: Fetching ensures the remote state is preserved locally, giving teams the ability to restore branches if accidents occur.

- Release management: Pull is useful when preparing a release branch that must quickly integrate final changes from main before deployment.

- Hotfix scenarios: Fetch lets you inspect urgent patches without risking your local branch until you’re ready to merge them.

Conclusion

Both commands are essential but serve different purposes. git fetch emphasizes safety, visibility, and controlled integration, while git pull emphasizes speed and convenience. The choice between them depends on context: project size, team culture, and the balance between stability and agility.

Teams should strike the right balance between using fetch for careful review and pull for quick updates. You'll be able to prevent unnecessary conflicts, streamline collaboration, and maintain healthier repositories.

Want to learn more about using Git for version control? Check out our GitHub Foundations track or our GitHub Concepts course. Want to read more about Git? Then our Git Push and Pull and Git Remote tutorials might be helpful.

Git Fetch vs Git Pull FAQs

How does git fetch help in avoiding merge conflicts?

git fetch downloads new commits from the remote without touching your working tree or current branch. Because it doesn’t auto-merge, you can review changes (diff/merge-base), update your branch incrementally (e.g., rebase on the fetched tip), and resolve small conflicts locally before they snowball.

What are the best practices for using git pull in a team environment?

Use git pull --rebase (or set git config pull.rebase true) to keep a linear history for feature branches. Pull frequently, but only with a clean working tree. Use small, focused commits; test before pushing. Protect main branches, require reviews/CI, and avoid pulling directly into release branches while mid-work. When shared branches diverge a lot, consider --ff-only to fail fast instead of creating messy merge commits.

Can you explain the differences between git merge and git rebase?

git merge combines histories and creates a merge commit, preserving the true chronology (good for shared branches and audit trails). git rebase rewrites your commits to “sit on top of” a new base, creating a linear history that’s easier to read (best for your own feature branches before they’re shared).

How does git pull --rebase differ from git pull --merge?

Both fetch then integrate. --rebase rewrites your local commits on top of the fetched upstream—no merge commit, cleaner history, but you’ll resolve conflicts during the reapply step. --merge performs a standard merge, keeps all original commits, and adds one merge commit, which can be clearer for branch topology but grows noise if used oft

What are the risks associated with using git pull force?

It forces updating remote-tracking refs even if that’s a non–fast-forward. That can hide upstream history rewrites, unexpectedly replace tags, and confuse subsequent merges/rebases. While it doesn’t directly overwrite your current branch, it can lead you to integrate a rewritten history incorrectly and lose work.