Track

A machine learning model with 98% accuracy sounds impressive–but is it? When you are dealing with rare events like fraud or disease, accuracy often creates a false sense of security.

That is where precision and recall come in. In this article, we will look at how these two metrics go beyond simple accuracy to measure not just how often you are right, but exactly how you are wrong.

If you want to move beyond theory and master classification, the Fraud Detection in Python course is the perfect next step.

Why Accuracy Is Not Enough

In most situations, accuracy is the natural metric used to measure how well a statistical or machine learning model predicts a certain label. It is calculated by comparing the number of correctly predicted instances to the total number of observations.

Generally speaking, if a model consistently identifies the correct label with high accuracy, it is working well. However, imbalanced datasets, in which one class contains significantly more samples than the other, distort accuracy. Such datasets are common in fraud detection or disease diagnosis.

Let’s suppose a model classifies fraud with a 98% accuracy rate. At first blush, this rate seems fantastic. But what if fraud only accounts for 2% of the transactions in the dataset? In this case, a model could choose "not fraud" every time and still get that 98% accuracy rate while catching zero fraud, which is not what we want.

Clearly, these kinds of situations require more nuanced metrics. Two commonly used metrics are precision and recall.

What Are Precision and Recall?

Here is the short version:

- Precision (Quality): Measures how trustworthy your positive predictions are. If the model says "fraud," is it actually fraud?

- Recall (Quantity): Measures how well you captured the actual positive cases. Did the model catch all the fraud, or did some slip through?

To understand how to calculate these metrics, however, we first need to define the terminology used in a confusion matrix.

True positive, false positive, and negatives

Consider a credit card company that uses a machine learning model to detect fraudulent credit card transactions. Suppose that for a sample of 10,000 transactions, there were 9,800 legitimate transactions and 200 instances of fraud.

To measure the effectiveness of the model, designate one of "fraud" or "not fraud" as the positive case and the other as the negative case. Since the fraud cases are of interest, label these as the "positive" cases. (This, of course, doesn't imply that fraud is positive in an ethical sense; the “positive” label just signifies which case we're interested in.)

When the model is run, transactions with a risk score above a certain probability threshold, say 70%, are considered to be fraud. The cases predicted to be fraudulent are compared to those that actually are.

To keep all this data straight, we use the following nomenclature.

- True positives (TP): 160 fraud cases were correctly predicted to be fraud.

- True negatives (TN): 9500 cases were correctly identified to be non-fraud.

- False positives (FP): 300 cases were incorrectly flagged as fraud.

- False negatives (FN): 40 cases were incorrectly marked as non-fraud.

The second letter (P or N) indicates whether the prediction was positive or negative, and the first letter shows whether that prediction was true (T) or false (F).

A "false positive" indicates that the system predicted the case to be positive, but it was actually negative. For instance, a false negative is a case that was predicted to be negative, yet is actually positive.

Confusion matrix

All this information is commonly displayed in the so-called confusion matrix, which tracks how often the model confuses incorrect predictions with actual results (FN, FP). The confusion matrix helps us distinguish between what the model predicted and what actually happened. The confusion matrix of our example looks like this:

|

Actual fraud (actual positive) |

Actual legitimate(actual negative) |

|

|

Predicted fraud(predicted positive) |

160 (TP) |

300 (FP) |

|

Predicted legitimate(predicted negative) |

40 (FN) |

9500 (TN) |

Now, let's take a look at the row and column totals. The row sums indicate total predicted cases, and the column sums indicate total actuals.

|

Actual fraud (actual positive) |

Actual legitimate (actual negative) |

||

|

Predicted fraud (predicted positive) |

160 (TP) |

300 (FP) |

460 (TP + FP) Total predicted positives |

|

Predicted legitimate (predicted negative) |

40 (FN) |

9500 (TN) |

9540 (FN + TN) Total predicted negatives |

|

200 (TP + FN) Total actual positives |

9800 (FP + TN) Total actual negatives |

10,000 |

What do these totals represent?

- The first row total (460) represents the total number of predicted fraud cases (TP + FP).

- The second row total (9,540) represents the total number of predicted legitimate cases (FN + TN).

- The first column total (200) represents the total number of actual fraud cases (TP + FN).

- The second column total (9,800) represents the total number of actual legitimate cases (FP + TN).

- The grand total (10,000) equals the total size of our sample.

What is precision?

Precision measures the quality of your positive predictions. It tells us how many cases predicted to be positives were actually positives.

A precise model means having very few false alarms. If the model says something is true, it most likely is true. For instance, if an online game bans someone for cheating, it needs to be true. Too many undeserved bans alienate legitimate users and lead to negative reviews.

In the terminology examined above, precision equals the ratio of true positives to predicted positives.

In the example above, precision is 160/460, or about 34.8%.

What is recall?

Recall measures coverage. It shows us how many of the actual positives were predicted as such. It is defined as the ratio of true positives to total actual positives.

Consider cancer diagnoses for initial follow-up. Is it better to err on the side of over-diagnosing or under-diagnosing? Most people would agree on the former.

For early screening, it can be shocking to receive a false alarm. But it is catastrophic to be told you don't have cancer when you actually do, especially considering you might miss a potentially life-saving treatment.

In the example above, recall is 160/200, or 80%.

The Trade-off Between Precision and Recall

There is a tug-of-war relationship between precision and recall. Typically, as precision increases, recall decreases, and vice versa.

To see why, let's revisit the fraud example.

Most fraud was caught, but there were many false positives. Let’s say, because of customer complaints, management decided to increase the decision threshold from 0.7 to 0.8. For a transaction to be flagged as fraud, it must now have a score of at least 0.8 instead of 0.7.

This made the model more conservative. It predicted fraud less often. Fewer transactions were flagged incorrectly as fraud, but at the cost of more truly fraudulent cases slipping through. After changing the threshold, the number of false positives decreased from 300 to 60, but the number of false negatives increased from 40 to 80.

The confusion matrix of the new model looks like this:

|

Actual fraud (actual positive) |

Actual legitimate (actual negative) |

||

|

Predicted fraud (predicted positive) |

120 (TP) |

60 (FP) |

180 (TP + FP) Total predicted positives |

|

Predicted legitimate (predicted negative) |

80 (FN) |

9740 (TN) |

9820 (FN + TN) Total predicted negatives |

|

200 (TP + FN) Total actual positives |

9800 (FP + TN) Total actual negatives |

10,000 |

As we can see, 120 of the 180 predicted fraud cases were actually fraudulent, so the precision increased from 34.8% to 66.7%.

The price for this increased precision lies in a reduced recall: 120 of 200 fraudulent cases were predicted as such, which means the recall dropped from originally 80% to now only 60%.

The model now catches fewer fraud cases overall, but when it does flag fraud, it's much more confident. It shows us the importance of balancing both metrics, which we’ll get to later.

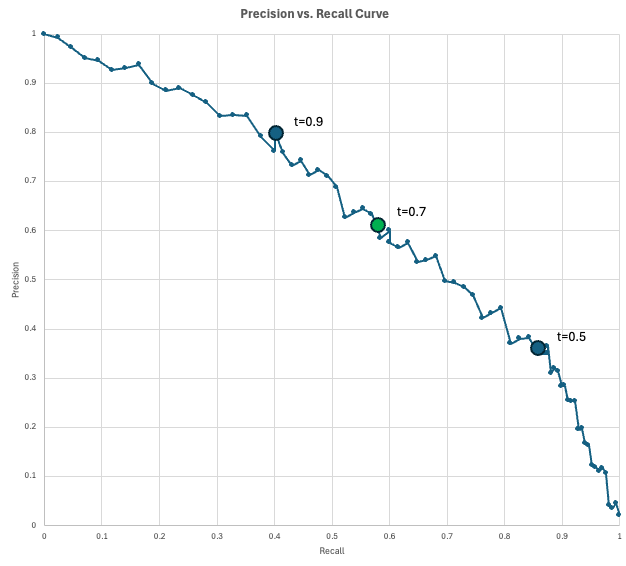

The precision-recall curve

To visualize the trade-off between precision and recall, data scientists use the Precision-Recall (PR) curve.

This chart plots precision on the y-axis and recall on the x-axis for every possible decision threshold (from 0 to 1). As you lower the threshold to capture more positive cases (increasing recall), you inevitably flag more false alarms (decreasing precision).

The "perfect" model would reach the top-right corner (100% precision and recall), but in reality, you must choose a point on this curve that meets your specific business requirements.

In our fraud example, we have a model that outputs a fraud score for each transaction. If a transaction's score is at least the threshold, then it is flagged as fraud. As we lower the threshold, we get more predicted positives, which typically captures more true positives (increasing recall) but also more false alarms (decreasing precision).

Let's see what all this might look like in practice. Suppose your company processes 10,000 transactions per day. Since the fraud rate is estimated to be 2%, you expect 200 fraudulent transactions per day. Also, suppose the fraud operations team can review 200 flagged transactions (predicted positives) per day.

You evaluate a few thresholds and find these results:

- At a threshold of 0.9, there are 100 predicted positives, with a precision of 0.8 (80 actual fraud, 20 false alarms), and a recall of 0.4 (you catch 80 of 200 fraud cases). You are underusing capacity because you only flag 100 per day when you could review 200 per day.

- At a threshold of 0.5, there are 500 predicted positives, with a precision of 0.35 (175 actual fraud, 325 false alarms), and a recall of 0.875 (you catch 175 of 200 fraud cases). At this threshold, you are over capacity, since you cannot review 500 flagged cases.

- At a threshold of 0.7, there are 200 predicted positives, with a precision of 0.6 (120 actual fraud, 80 false alarms), and a recall of 0.6 (you catch 120 of 200 fraud cases). This is probably the threshold you'll use, as you can use the full capacity while still getting a somewhat decent recall of 0.6.

The curve tells you what precision you can buy at a given recall rate (or vice versa).

When To Use Precision vs. Recall

Because of the trade-off relationship between precision and recall, the correct metric depends on your particular use case.

When to use precision

There is an inverse relationship between precision and false positives. Therefore, a precise model is one that correctly differentiates between true positives and false positives. It is trustworthy.

Optimize for precision when the cost of a false positive is high. Examples of cases include:

- Irreversible actions: Automated justice or account-banning systems. Accusing an innocent person or permanently deleting a user's account due to a model error (False Positive) causes irreparable damage.

- High-cost interventions: Drilling for oil or shutting down a factory assembly line. If acting on a positive prediction costs millions of dollars, you need to be sure the prediction is correct before moving forward.

- Spam filtering: Email inboxes. It is annoying to see a spam email (False Negative), but it is unacceptable to have an important job offer sent to the junk folder (False Positive).

When to use recall

Similarly, there is an inverse relationship between recall and false negatives. Many false negatives induce a low recall. Accordingly, a model with high recall correctly differentiates between true positives and false negatives. It is safe.

If it is more important to avoid missing a real case than it is to accept false alarms, you should prioritize the recall metric over precision. Example use cases include:

- Medical safety: Disease screening (e.g., cancer or sepsis). Missing a sick patient can be fatal, whereas a false alarm leads to further testing, which is a tolerable cost.

- Cybersecurity: Malware detection or network intrusion. It is better to flag a few innocent logins as suspicious than to let a single hacker breach the system undetected.

- Manufacturing quality: Defect detection. Shipping a defective product (False Negative) creates safety liabilities and reputational ruin, so it is better to discard a few borderline items than let a bad one pass.

F1 Score For Balancing Precision and Recall

If you are unsure whether to optimize a model for precision or recall, or simply want to take both into account, you can consult the F1 score.

The F1 Score is defined as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, and is used when you want to aim for a balance between the two metrics.

If precision and recall are equal, the F1 score is equal to that value. If one of the two approaches zero, however, F1 will also be very low.

In the example above, precision is 66.7% and recall is 60%. Using the formula mentioned above, we get a F1 score of about 63.2%:

The following table compares the F1 score to accuracy, precision, and recall.

|

Metric |

Question it answers |

When to optimize on this metric |

Examples |

|

Accuracy |

"How often are we correct overall?" |

Classes are balanced, and FP and FN costs are similar. |

Digit classification. |

|

Precision |

"Of all predicted positives, how often were we correct?" |

When FPs are expensive, punitive, or create customer pain. |

Fraud blocks, banning users, and invasive medical actions. |

|

Recall |

"Of all actual positives, how many did we flag?" |

False negatives are unacceptable. |

Medical screening, intrusion detection. |

|

F1 |

"What is the balance of precision and recall?" |

You care about both: positives and false alarms. |

Early model selection for imbalance problems. |

Calculating Precision and Recall in Python

There are many ways to calculate precision, recall, and the F1-score in Python. In the following, I will present two approaches: applying the formulas directly and using designated formulas in the scikit-learn package.

Calculating precision and recall using the formulas

If you know the numbers of the confusion matrix, you can easily calculate the metrics using their formulas presented above.

# Confusion matrix numbers

TP = 120

FP = 60

FN = 80

TN = 9740

# Formulas

precision = TP / (TP + FP)

recall = TP / (TP + FN)

f1 = 2 * precision * recall / (precision + recall)

# Output

print(f"{'Precision':<10} {precision:.1%}")

print(f"{'Recall':<10} {recall:.1%}")

print(f"{'F1':<10} {f1:.1%}")Precision 66.7%

Recall 60.0%

F1 63.2%The output of this code agrees with our earlier calculations.

Calculating precision and recall using scikit-learn

You can also learn the scikit-learn library to calculate metrics from the data itself. In the following example, we simulate y_true and y_predicted. We then calculate precision using the method precision_score(y_true, y_false). We calculate recall and the F1 score similarly. Finally, we will output the results.

import numpy as np

from sklearn.metrics import precision_score, recall_score, f1_score

# Simulate Data (y_true and y_pred)

TP, FP, FN, TN = 120, 60, 80, 9740

y_true = np.array(TP * [1] + FP * [0] + FN * [1] + TN * [0])

y_pred = np.array(TP * [1] + FP * [1] + FN * [0] + TN * [0])

# Compute metrics with scikit-learn

precision = precision_score(y_true, y_pred, zero_division=0)

recall = recall_score(y_true, y_pred, zero_division=0)

f1 = f1_score(y_true, y_pred, zero_division=0)

# Print aligned output using f-strings (no manual spaces, no colon)

print(f"{'Precision':<10} {precision:.1%}")

print(f"{'Recall':<10} {recall:.1%}")

print(f"{'F1':<10} {f1:.1%}")Precision 66.7%

Recall 60.0%

F1 63.2%As expected, these numbers agree with our earlier calculations.

Conclusion

While accuracy is a helpful starting point, it often hides the details you need to understand why a model is failing. Precision and recall give you a clearer picture by forcing you to look at the trade-off between false alarms and missed detections.

Ultimately, choosing the right metric isn't just a math problem; it is a practical decision about which type of mistake your system can afford to make.

Ready to build your own machine learning models? Start with the Machine Learning Fundamentals in Python skill track today!

Precision vs Recall FAQs

What is the difference between recall and precision?

Precision measures the quality of your positive predictions. It tells us how many cases predicted to be positives were actually positives and is defined as the ratio of true positives to predicted positives.

Recall measures coverage. It shows us how many of the actual positives were predicted as such. It is defined as the ratio of true positives to total actual positives.

Which metric should I optimize to reduce false positives?

Precision. Low precision indicates the model is flagging too many items as positive that aren't.

Which metric should I optimize to reduce false negatives?

Recall. Low recall indicates that real positives slip through.

Which metric matters more in a medical diagnosis?

Recall. Some false alarms can be tolerated if it means fewer missed diagnoses.

Which metric matters more in a spam filter?

Precision. Misclassifying a spam email is annoying, but losing an important email is unacceptable.

Mark Pedigo, PhD, is a distinguished data scientist with expertise in healthcare data science, programming, and education. Holding a PhD in Mathematics, a B.S. in Computer Science, and a Professional Certificate in AI, Mark blends technical knowledge with practical problem-solving. His career includes roles in fraud detection, infant mortality prediction, and financial forecasting, along with contributions to NASA’s cost estimation software. As an educator, he has taught at DataCamp and Washington University in St. Louis and mentored junior programmers. In his free time, Mark enjoys Minnesota’s outdoors with his wife Mandy and dog Harley and plays jazz piano.