There are various ways you might hear the name Alan Turing: you might have watched the famous Benedict Cumberbatch film The Imitation Game. You might be wandering around Manchester and see his statue sitting on a bench just outside an area called “The Gay Village”. One day you might finally see, or even use, a £50 note, and if you look at one side you’ll see the face of the man. But since you’re on DataCamp, chances are you first heard his name when getting to know artificial intelligence and machine learning. For all the talk of AI in this day and age and how it will affect the future, it can be easy to forget that it was invented during the Second World War by a man whose brain won Britain the war in intelligence, and hastened the peace that followed.

Chapter I: A War of Wits

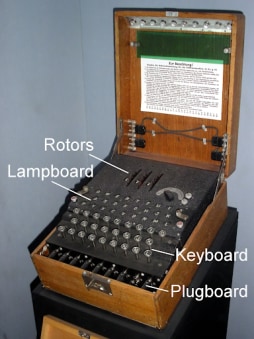

Encryption works on the basis of replacing the letters of a message with others in accordance with a system known as a cypher. A very basic cypher might be that every letter gets replaced with two letters ahead in the alphabet, so that “hello” gets spelled as “jgnnq”. Code-breakers in World War II could break this very easily, so more complicated cyphers were needed. And enigma devices, used extensively by the German military, provided that complication.

At its most basic level, one types out a letter which causes a corresponding letter on a keypad to light up. Which letter could light up was dictated by the arrangement of rotors and a plug board in the machine, and this arrangement was enigma’s cypher. This design meant there were 159 quintillion ways messages could be written out (that number is neither made up nor exaggerated). To further complicate matters, Enigma’s cypher was one that changed daily, written out in a book that each operator carried so that they could adjust the settings of their device. Code books were only set for the month ahead and could be sabotaged by being thrown in water, so even if the allies did manage to obtain one by force a more permanent solution was needed.

Turing and his team at Bletchley Park, the UK’s centre of code-breaking efforts, needed a way to know how the enigma machines had been set up that day, and quickly so that intelligence could be relayed in good time. And so, they developed a machine known as the Bombe, which when fully functional could crack enigma messages in under twenty minutes. Based on Turing’s earlier work with machines and mathematics, Bombe worked by process of elimination and mimicry of enigma’s systems. The Bombe could confirm if pairings of letters corresponded to one another and therefore show the operator the way rotors and plugs had been set up that day. And how did they decide which pairings to go with?

Enigma’s biggest flaw was the fact that a letter would never be written as itself, and so this meant a word in German could be compared to a set of letters in the encrypted message. If none of the letters matched up it was a possible combination. Turing’s team would predict these words themselves: as the Germans were sending out daily weather reports, they would look for the word “weather” in German. When the Royal navy planted mines, staying in contact with Bletchley, they would look for the word “mine”. And another set of words they would look for, for obvious reasons, was “heil Hitler”.

Because only one plug could be put into a socket at a time, the Bombe could identify and eliminate impossible combinations until it was only left with settings that made logical sense. Turing’s team, and later the entirety of Bletchley Park, were then able to enter the encrypted messages into captured enigma devices, calibrated the correct way, and obtain the message in plain German.

Cracking enigma was a major victory for the allies that they did not even realize they had won outside of military intelligence circles (and nor did the Germans, until 1974). It was used in almost every military campaign, from Norway to North Africa to Normandy. Yet the most crucial difference cracking enigma made was the ability to know the positions of German submarines known as U-boats. Roaming the North Atlantic, these mechanical sea monsters were the terror of every sailor running the gauntlet between Britain and the US, a vital supply line between the only allied nation in Europe and the industrial powerhouse of the world. Churchill said they were the only thing he had feared during his time as Prime Minister. Discovery of their positions enabled allied convoys to be diverted away from the threat and prevent the UK from starving—and for allied navies to close in for the kill.

This part of the story tends to end with historians’ estimates that breaking enigma shortened the war by two years and saved 14 million lives. And that is true, but there is something more that needs to be said: people who theorize Germany could have won the war often do so on the basis that technologies they were developing in the war’s late stages could have given them the upper hand had it not been for the war coming to an end before they could be deployed. Most historians are in agreement that at the least it would have made the war far more destructive, so the bottom line is: 14 million lives is a very conservative estimate.

Photo credit: TS on Unsplash ## Chapter II: The Mind of a Machine Turing’s story might have ended with WWII and thanks to the Official Secrets Act might not have been known to the public until much later. He continued to work at Bletchley Park for two years until he felt that the culture of secrecy was hindering his work, and subsequently transitioned into civilian life. In 1936 Turing had already laid the foundations of what came to be known as Turing Machines, machines capable of solving any mathematical problem through algorithms, and Turing built upon these during this period when working upon the earliest iterations of computers. In 1950 he published what might be his most influential piece, a philosophical paper that began with the question “Can Machines Think?” He theorized that the human brain, through training, education, and life experiences, becomes a “universal machine”, and therefore it ought to be possible to construct a machine that can take prior information into account and learn likewise. This was how Turing came to be known as the father of artificial intelligence. Turing proposed a test that would confirm if a brain had been built called the Imitation Game. Based on an earlier Victorian parlor game, it would involve a human judge having a conversation with a machine, though not knowing this for a fact. If, through speech patterns, word choice, etc, the machine could fool the judge into thinking they were having a conversation with a human, the machine passed the Turing Test. Turing’s theory was that by the year 2000 a machine could easily have passed this test. The involvement of Turing’s brilliance could well have meant this prophecy would have been fulfilled. But a year later, Turing’s story entered a much darker phase. ## Chapter III: Betrayal Alan Turing was a homosexual man born into a homophobic England. In the Victorian era laws criminalizing homosexual behavior had been passed, and were active and applied over half a century later when it was discovered that Turing had been having a relationship with a man called Arnold Murray. Turing had been open about his homosexuality during his time at King’s College, described as “an oasis of acceptance” in an otherwise intolerant society. He kept it a secret during his time at Bletchley Park except in 1941 when he revealed it to his fiancee and colleague Joan Clarke, deciding he could not proceed with the engagement. His former colleague Professor I.J. Good later remarked “it was probably a good thing that the security people didn't know because he might then have been fired and we might have lost the war". Turing was offered the choice between prison and chemical castration, with him choosing the latter so that he could continue his research work. Taking medications designed to render him impotent, these along with the stripping of his security clearance and ability to travel abroad reportedly caused a depression that would eventually lead to his suicide by eating a cyanide-laced apple. Ideas are impossible to kill, however. As Britain transitioned into a more tolerant society Turing became an icon in the LGBTQ+ world. In 2009 Prime Minister Tony Blair issued an apology on behalf of the British government for how Turing had been treated, and four years later Queen Elizabeth issued a Royal pardon. 2015 saw the introduction of a set of laws that pardoned 49,000 men convicted under the act, wiping their criminal records clean. These were informally called the Alan Turing laws. ## Chapter IV: Data Science and the LGBTQ+ community Imagining what would have happened if Turing were able to see the world as it is now is not that hard to do. Born 109 years ago, had he lived a long and happy life he would still have been with us. He would have been both delighted and disappointed.

We’ve written a lot about the ethics of AI and data science as a whole here at DataCamp, and the common thread is that it can only be as ethical as the people and the data behind it. As data science affects more of our daily lives, this holds true for the LGBTQ+ community, and there are cases of it being used wrongly that would truly shock Mr Turing. There was the case of Google’s Sentiment Analyzer assigning negative sentiment to the phrase “I’m a homosexual”. There was the instance of a propaganda campaign targeting individuals identified as LGBTQ+ (through their Facebook data) with adverts to persuade them to not vote in the 2016 US Presidential elections. And there was the exceptionally amoral case of an AI that could purportedly identify homosexual individuals through facial analysis.

However when one adds the good to the bad, there are more reasons to believe Mr Turing would have been pleased by what he saw. There are examples of apps such as Geosure using data to protect LGBTQ+ travelers, and dating apps using human-assisted AI to verify profiles and protect users, of whom LGBTQ+ individuals make up a significant portion. More broadly speaking, data has been used to combat anti-LGBTQ+ misconceptions, and data science is by and large a progressive field that welcomes people of every background, including sexual orientation.

Final words

Alan Turing was a brilliant man who was instrumental to protecting what would become the free world and paved the way for technologies that dominate the headlines today. He was a man ahead of his time who sadly got punished for it by a prejudicial system. The world was robbed of a gift—yet not entirely. The fact that I write and you read this from what was once a Turing Machine is testament to that. And so, to honor the memory of a great man, let us ensure that our technological accomplishments are matched, nay, exceeded, by our moral ones.

Additional details

This article could have been much longer than it was had we not glossed over certain details, that nonetheless bear some mentioning for the curious reader.