Track

Users and followers, students and courses, customers and products: our world is full of natural many-to-many relationships. However, these are not always translated well into database designs. Poorly designed many-to-many relationships are one of the most common sources of data duplication, incorrect analytics, and long-term maintenance pain in production systems.

In this article, I’ll go over many-to-many relationships from first principles through real-world implementation. We will also explore advanced design patterns, normalization, performance considerations, and how many-to-many relationships are implemented across relational and NoSQL systems.

By the end, you should be able to design scalable, maintainable schemas that correctly model complex relationships, avoid data anomalies, and support reliable reporting and BI workflows.

For readers who want to reinforce fundamentals along the way, I recommend taking our Introduction to Relational Databases in SQL course.

What Is a Many to Many Relationship

A many-to-many relationship (M:N) is a bidirectional database relationship where each record in Table A can relate to many records in Table B, and each record in Table B can relate to many records in Table A. Unlike simpler relationship types, cardinality exists on both sides.

This relationship is ubiquitous in real systems:

- Education: A student can enroll in many courses, and each course can have many students.

- E-commerce: A product can belong to multiple categories, and each category can contain many products.

- Social platforms: Users can join many groups, and groups can contain many users.

- Healthcare: A patient can be prescribed multiple medications, and each medication can be prescribed to many patients.

The relationship carries meaning and often data of its own. Understanding this distinction is critical for correct schema design and querying, especially when joining tables for analytics.

Many-to-many vs one-to-many relationship

To understand why many-to-many relationships require special handling, it helps to contrast them with simpler cardinalities.

- One-to-one (1:1): Each record in Table A relates to exactly one record in Table B, and vice versa (e.g., a user and a user profile).

- One-to-many (1:N): One record in Table A can relate to many records in Table B, but each record in Table B relates to only one record in Table A (e.g., a customer and their orders).

|

Relationship Type |

Description |

Logic |

Example |

|

One-to-One (1:1) |

Each record in Table A relates to exactly one in Table B. |

Unique pairing. |

User ↔ User Profile |

|

One-to-Many (1:N) |

One record in Table A relates to many in Table B, but Table B records only have one parent. |

Parent/Child structure. |

Customer → Multiple Orders |

|

Many-to-Many (M:N) |

Multiple records in Table A relate to multiple records in Table B. |

Bidirectional web. |

Students ↔ Courses |

For example, in a one-to-many design, an orders table typically contains a customer_id foreign key with each unique order having an order_id. Each order belongs to exactly one customer, but a customer can have many order_id keys.

Now contrast this with the student–course example. If you attempt to store course_id directly on the students table, each student would be linked to multiple course_id values. Conversely, inside the course table, each course would have multiple student_id references. Instead of a neat one-way relationship, both directions share information back and forth.

First Normal Form Violation and the Many-to-Many Problem

A common issue is attempting to represent many-to-many relationships directly by storing multiple values in a single column using an array of (e.g., course_ids on a students table) or repeated columns like course_1, course_2, course_3.

This approach violates First Normal Form (1NF), which requires that each column contain atomic, indivisible values. Read this blog on normalization in SQL for a refresher.

Violating 1NF leads to classic update anomalies:

- Insertion anomalies: Adding a new relationship requires modifying an existing row structure.

- Update anomalies: Changing a relationship requires updating multiple rows, multiple columns, or embedded values, increasing the risk of inconsistency.

- Deletion anomalies: Removing one relationship may accidentally remove unrelated information.

Beyond normalization theory, there is a severe analytical consequence known as the many-to-many problem. When tables with a many-to-many relationship are not joined carefully, it can easily lead to row multiplication. This can cause issues with compute time and aggregation errors for analysis.

For example, joining courses to students based on student_id may cause each course to be joined multiple times due to multiple student entries. Then attempting aggregation can lead to analytical discrepancies like revenue or student counts.

Correct schema design directly affects reporting accuracy, financial calculations, and trust in data products. Plus, it helps simplify joins to minimize human error. For more details on common join pitfalls, look at this SQL join tutorial and practice on these Top 20 SQL Joins Questions.

Junction Tables: Foundation and Structure

The standard solution to many-to-many relationships in relational systems is the junction table (also called a join table, bridge table, or associative table). Instead of trying to store relationships directly, you introduce an intermediate table that references both parent tables.

Conceptually, this transforms A ↔ B into A ← JT→ B.

Now, each has a one-to-many relationship with the junction table, allowing for a simplified analytical schema. I’ll go over how we build up these junction tables and how they are utilized.

Anatomy and components

A basic junction table contains:

- One foreign key referencing the primary key of Table A

- One foreign key referencing the primary key of Table B

In most cases, these two foreign keys together form a composite primary key. This guarantees that the same relationship cannot be inserted twice and enforces uniqueness at the database level.

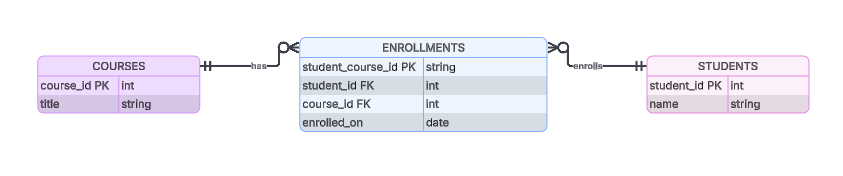

For example, an enrollments table might use a concatenation of student_id and course_id as its primary key. The database now has a unique reference key for the relationship and we can start building business use cases.

Example of what an enrollments junction table might look like.

Adding attributes to junction tables

When a junction table stores additional attributes, it becomes closer to an associative entity rather than a purely structural artifact. This allows the junction table to contain contextual information about the relationship. Common examples include:

-

Date:

enrollment_date,creation_date, and similar time-based information -

Role: e.g., admin vs member in a group

-

Metrics: relevance scoring in recommendation systems

This helps the relationship carry more meaning. Query complexity increases slightly, but the schema more accurately models reality. This trade-off is almost always worth it in systems where relationships evolve over time. We can add more information and make junction tables a useful analytical tool.

Maintaining data integrity

Junction tables rely heavily on referential integrity. Foreign key constraints ensure that every relationship row references valid parent records, preventing orphaned data.

Deletion rules matter:

- CASCADE: Automatically remove junction rows when a parent is deleted.

- RESTRICT / NO ACTION: Prevent deletion of a parent row if relationships still exist.

The choice depends on business semantics. In some domains, automatic cleanup is appropriate; in others, historical relationships must be preserved or explicitly reviewed before removal.

Normalization and junction tables

Junction tables are a direct application of the Third Normal Form (3NF). They eliminate transitive dependencies and remove redundant storage of relationship data. Its entire goal is to improve the normalization within the database.

In many cases, junction tables also help satisfy Boyce–Codd Normal Form (BCNF) because the composite primary key fully determines all non-key attributes. This matters because it minimizes update anomalies and guarantees that modifying a relationship requires changing exactly one row.

For a deeper understanding of the importance of ensuring 3NF in our databases, check out this article on transitive dependency.

Designing and Implementing Many to Many Relationships

Let’s discuss how we can actually build our databases to support many-to-many relationships. We’ll cover good practices for making your life easier.

Naming conventions and schema clarity

Clear table naming reduces cognitive load and improves maintainability. Common conventions generally include TableA_TableB or join_TableATableB, for example:

-

student_course -

user_group -

join_user_group

Column names should mirror parent table primary keys (e.g., student_id, course_id) to make joins obvious and readable. Consistency becomes critical as schemas grow and teams expand.

Common patterns and variations

There are a few different ways we can build our junction tables from very simple relationship tracking to more complex polymorphic relationships.

Simple junction tables

Simple junction tables contain only foreign keys and are ideal for static or low-context relationships. These are very simple to maintain with minimal overhead as they are typically only concerned with showcasing how two tables are related. These junction tables have no temporal or contextual data.

Self-referencing many-to-many relationships

Self-referencing many-to-many relationships occur when both foreign keys reference the same table.

For example, if we’re tracking a social media app which includes tracking users, their followers, and who they’re following we might have a relationship of user_id to follower_id in both directions. Additional constraints may be required to prevent invalid or symmetric duplicates.

Polymorphic many-to-many relationships

Polymorphic many-to-many relationships allow one junction table to connect multiple entity types using a type discriminator. This provides flexibility but shifts integrity enforcement into application logic and complicates queries.

For instance, a junction table called Tag for social media apps could relate Posts, Comments, and Users with an additional contextual column for associating the tag with the proper entity.

Temporal and weighted relationships

Temporal and weighted relationships both store information about the relationship in additional attributes.

Temporal many-to-many relationships add columns that provide temporal information, such as active_from, active_to, or created_on, to track historical validity. The enrolled_on key in our earlier student-course database is one example of a temporal relationship.

These are essential for audit trails, slowly changing relationships, and point-in-time analysis. This adds a little complexity where users must be careful to filter on the proper temporal scale and consider rows that may be inactive.

Weighted relationships, on the other hand, store ranking or strength metrics. Recommendation engines, tagging systems, and relevance scoring commonly rely on this pattern to track things like recommendation confidence.

Multi-way relationships

While most OLTP systems avoid relationships involving more than two entities, analytics systems frequently use them. Fact tables in dimensional models effectively act as junction tables connecting tables at varying levels of granularity. These designs are powerful but require disciplined querying and clear documentation.

A potential design would be to create your junction table with foreign keys to all participating entities.

For instance, if we build on our student and course example, a third table could be classroom numbers. A junction table may contain the foreign keys for a student in a particular class in a particular room. It’s easy to see that as we expand the number of relationships, querying and schema become exponentially more complex.

For a deeper dive into building databases, make sure to take our course on database design.

Performance Optimization and Query Efficiency

With any complicated database design, we have to look at performance and query considerations. The more pieces we add, the more likely we’ll run into performance bottlenecks!

Query patterns and optimization

Let’s first look at some ways we might query our junction tables. Common access patterns include:

- Fetching all related entities from Table B for a given entity in Table A

- Counting relationships

- Filtering by relationship attributes

To optimize these queries:

-

Index foreign keys in the junction table

-

Use

GROUP BYorDISTINCTto prevent over-counting -

Consider covering indexes for read-heavy workloads

-

Be specific about

WHEREstatements to limit how much data is being joined.

These techniques are foundational for efficient joins and aggregations. Remember, too, if you are trying to use the junction table to bridge two tables, it’s good to think about how you might join three tables efficiently.

Bulk operations and concurrency

Junction tables often see high write volume. Batch inserts and updates reduce transaction overhead.

However, high contention on popular foreign keys can create locking bottlenecks. Make sure to monitor performance and partition tables to allow for parallelization.

Normalization vs denormalization

Let’s take a second to look at the key difference between normalization and denormalization as an approach to our database design:

- Normalized designs suit write-heavy, consistency-critical systems (e.g., finance, ERP). If strict consistency with no chance of duplication or extraneous data is required, focus on a strictly normalized design.

- Denormalized designs suit read-heavy analytics where eventual consistency is acceptable. If data accessibility is more important, where we are okay with data “settling” later, then we can use a denormalized design, given we are providing strict guidance on best practices.

Really think about access patterns, team expertise, and operational constraints.

Denormalization trade-offs

Denormalization can improve performance on write-heavy systems that don’t frequently change. The cost is added complexity, an increased maintenance burden, and a risk of stale data.

My two cents: Denormalization should only be a measured response to read-heavy bottlenecks and should always be built with regular consistency checks .

Implementation Across Database Systems

SQL and NoSQL systems have slightly different approaches to the implementation of many-to-many systems.

Relational and NoSQL architectures

Relational databases such as PostgreSQL, MySQL, and SQL Server implement many-to-many relationships explicitly using junction tables with foreign keys and composite primary keys. Similarly, cloud-based relational databases like Snowflake follow a similar design pattern.

NoSQL systems often represent many-to-many relationships by embedding arrays of related IDs or storing references managed by application logic. This is due to the priority of read performance and horizontal scalability in NoSQL databases. This improves read performance and schema flexibility but sacrifices normalization.

|

Feature |

Relational (SQL) |

NoSQL |

|

Implementation |

Junction Tables: Uses a third table with foreign keys and composite primary keys. |

Embedding or Referencing: Uses arrays of IDs or nested documents. |

|

Primary Goal |

Normalization: Ensures data consistency and eliminates redundancy. |

Performance: Prioritizes read speed and horizontal scalability. |

|

Flexibility |

Rigid Schema: Requires predefined structures and joins to retrieve data. |

High Flexibility: Allows for schema-less designs and varied data types. |

|

Trade-off |

Complex Joins: Can become slower as the dataset grows significantly. |

Sacrifices Normalization: Can lead to data duplication or "stale" data. |

|

Examples |

PostgreSQL, MySQL, SQL Server, Snowflake. |

MongoDB, DynamoDB, Cassandra. |

SQL vs NoSQL

Relational databases are preferred when you need a well-defined schema structure. These databases are easier to manipulate and allow for better data management. Consider focusing on using a relational SQL database when:

- Relationships change frequently

- Integrity is business-critical

- Queries involve complex joins

NoSQL databases are suitable for situations where flexibility and bulk operability are priorities. For instance, NoSQL databases like MongoDB allow for the usage of operators like updateMany when we need to update across a multitude of documents. Here are some guiding principles for when you should consider a NoSQL implementation:

- Cardinality is predictable

- Reads vastly outnumber writes

- Schema flexibility outweighs strict consistency

Conclusion

Many-to-many relationships are unavoidable in realistic data models. Designing them correctly is critical for data integrity, scalability, and analytical correctness. Junction tables, when properly normalized and indexed, provide a robust foundation that scales from transactional systems to enterprise analytics.

Every design involves trade-offs: normalization versus performance, simplicity versus flexibility, and abstraction versus control. The key is to profile your access patterns, choose patterns aligned with your workload, and validate designs through schema review and query testing.

For practitioners looking to deepen their skills in database design, I highly recommend enrolling in our Associate Data Analyst in SQL career track.

Many to Many Relationship FAQs

What is a many-to-many relationship in a database?

A many-to-many relationship exists when each record in one table can relate to multiple records in another table, and vice versa. This requires an intermediate junction table in relational databases to maintain normalization and data integrity.

Why can’t many-to-many relationships be implemented directly in SQL tables?

Direct implementations typically violate First Normal Form (1NF) by storing multiple values in a single column or repeating columns, leading to update anomalies and unreliable query results.

What is a junction table, and why is it required?

A junction table (also called a bridge or associative table) stores foreign keys referencing both parent tables, converting a many-to-many relationship into two one-to-many relationships that relational databases can enforce.

When should additional attributes be added to a junction table?

Additional attributes should be added when the relationship itself has business meaning, such as enrollment dates, roles, weights, or validity periods.

Are many-to-many relationships common in data warehousing?

Yes. Fact tables in dimensional models often serve as multi-way junction tables that connect several dimensions at a defined grain, making many-to-many reasoning critical for accurate analytics.

I am a data scientist with experience in spatial analysis, machine learning, and data pipelines. I have worked with GCP, Hadoop, Hive, Snowflake, Airflow, and other data science/engineering processes.