Track

A neural network that refuses to converge, with loss stuck flat and gradients either vanishing or exploding, often turns out to have nothing wrong with its architecture at all. The problem is often much simpler: input features living on wildly different scales, where one column ranges from 0 to 1 while another reaches into the tens of thousands.

In my experience, this pattern shows up constantly in practice. Five minutes of preprocessing can resolve what days of hyperparameter tuning could not.

In this tutorial, I will show you how to normalize data. I'll walk you through different normalization techniques, and when each applies, Python implementations included. Additionally, you will learn about common mistakes and misconceptions and how to avoid them.

If you want to learn more about how to prepare data for machine learning algorithms, I recommend taking our Preprocessing for Machine Learning in Python course.

What Is Data Normalization?

Data normalization refers to the process of transforming numeric features so they occupy comparable ranges or follow a consistent scale.

The term carries different meanings depending on context: in machine learning, it typically means rescaling feature values to prevent magnitude from dictating importance, while in database design, it refers to organizing tables to eliminate redundancy.

I will focus primarily on the machine learning meaning, though we will briefly cover database normalization later to clarify the vocabulary overlap.

Why data normalization matters

When features exist on different scales, certain algorithms give disproportionate weight to whichever values happen to be numerically larger.

A feature measuring income in thousands will dominate one measuring age in decades, not because income matters more for the prediction task, but simply because the numbers are bigger. Normalization puts features on equal footing so the model can learn which ones actually matter.

Beyond model training, normalization also helps for:

- combining measurements that use different units

- integrating data from multiple sources with inconsistent conventions

- designing database schemas that need to maintain consistency over time.

Data normalization vs. scaling vs. standardization

So, what’s the difference between normalization, scaling, and standardization? These three terms appear frequently in documentation, often used interchangeably despite having distinct meanings.

The practical distinction comes down to whether your model needs values within specific limits. Min-max normalization guarantees bounds, while standardization does not. The following table summarizes the differences:

|

Term |

What It Does |

Output Range |

Best For |

|

Scaling |

General term for any range transformation |

Varies |

Umbrella category |

|

Normalization (min-max) |

Compresses to fixed bounds |

Typically 0 to 1 |

Bounded data, neural networks expecting specific input ranges |

|

Standardization (z-score) |

Centers at mean 0, scales to standard deviation 1 |

Unbounded (negative values possible) |

Unbounded data, algorithms assuming roughly normal distributions |

For a deeper comparison of when each approach backfires, our blog on Normalization vs. Standardization Explained covers the edge cases well.

Data Normalization Use Cases

Now that we’ve established the terms, let’s look at some classic use cases. Normalization serves different purposes depending on your use case, from improving model training dynamics to enabling meaningful comparisons across heterogeneous data sources.

Improve machine learning model performance

Neural networks and logistic regression update weights through gradient descent, where each feature's contribution to the prediction error determines how much the corresponding weight gets adjusted.

When feature magnitudes differ dramatically, the resulting gradients do too: large features produce large gradients, small features produce small ones. This imbalance causes the optimizer to take huge steps in some directions while barely moving in others, leading to unstable training or failure to converge at all.

Distance-based algorithms like kNN and K-means face a related problem. They compute similarity using distance metrics, typically Euclidean distance, where larger numeric values contribute more to the calculation simply by being larger. A feature spanning 0 to 10,000 will dominate one spanning 0 to 1, regardless of which feature actually matters for the prediction task.

Scaling ensures that all features contribute proportionally to their actual predictive value rather than their arbitrary numeric range.

Enable fair comparison across features

When building composite scores or combining measurements with different units, raw values can lead to misleading comparisons.

A customer health metric that combines monthly spending in dollars, login frequency as a count, and account age in days will weight dollar amounts most heavily simply because those numbers happen to be larger.

Normalization allows you to combine these measurements in a way that reflects their actual importance rather than their accidental magnitude.

This also applies to exploratory analysis and visualization. Plotting features on different scales makes it harder to spot patterns or compare distributions. Normalized data presents a cleaner picture of how features relate to each other.

Improve data quality and integrity

Production pipelines often pull from multiple data sources with inconsistent conventions. Revenue might be reported in dollars from one system and in thousands from another. Dates appear as Unix timestamps in one API and as formatted strings in another.

Establishing a consistent scale and format before downstream processing prevents subtle bugs that are difficult to diagnose later.

In database contexts, normalization takes on a different but related meaning: organizing tables so that each piece of information lives in exactly one place.

This prevents update anomalies where changing a value in one location leaves contradictory values elsewhere. While the techniques differ from feature scaling, the underlying motivation is similar: keeping data consistent and predictable.

Common Data Normalization Techniques

Each normalization approach makes different assumptions about your data and produces different output characteristics. The right choice depends on your data's distribution, the presence of outliers, and what your downstream model expects.

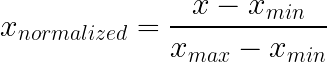

Min-max normalization

Min-max normalization compresses values into a fixed range, typically 0 to 1, by subtracting the minimum and dividing by the range. This approach preserves the original distribution shape while guaranteeing that all values fall within known bounds.

How it works: Subtract the minimum, divide by the range. That is it.

What it does:

- Guarantees output stays within defined bounds

- Preserves the original distribution shape—just rescaled

- Zero becomes your floor, one becomes your ceiling

Best used for:

- Pixel intensities (always 0-255 by definition)

- Probabilities and percentages

- Exam scores, ratings, anything with a natural floor and ceiling

- Neural networks that expect bounded input, like image classifiers

What to watch out for:

Outliers can wreck min-max normalization completely. Imagine some data mostly sitting between 10 and 100, but one value at 99,999? That single point stretches your range so far that everything normal compresses into a tiny sliver near zero. One bad observation, entire feature ruined.

Also consider what happens when new data falls outside the training range. Test values beyond the training maximum produce output above 1. Whether that breaks anything depends on your model.

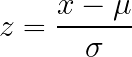

Z-score standardization

Z-score standardization transforms data so that the mean is zero and the standard deviation is one, without imposing fixed bounds on the output. This approach works well for data without obvious natural limits and is widely assumed or recommended by many algorithm implementations.

How it works: Subtract the mean, divide by the standard deviation.

What it does:

- Recenters everything so the average becomes zero

- Scales so one standard deviation equals one unit

- Output can go negative, can exceed any particular bound

Best used for:

- Data without obvious natural limits

- Roughly bell-shaped distributions

- Algorithms that assume or recommend standardization (most neural network tutorials, logistic regression implementations)

- When you are not sure what else to use (a reasonable default)

Tradeoff:

Interpretability takes a hit. "This observation is 1.7 standard deviations above average" requires more mental work than "this is at 80% of the range." If stakeholders need to understand scaled values directly, min-max might communicate better.

Outliers still inflate the mean and std dev, distorting the scaling for bulk data, but are less of a problem than in min-max normalization.

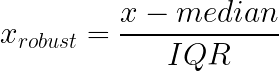

Robust scaling

Robust scaling addresses the outlier sensitivity of both min-max and z-score approaches by using median and interquartile range (IQR) instead of mean and standard deviation. These statistics remain stable regardless of extreme values in the tails of your distribution.

How it works: Subtract the median, divide by the IQR (gap between 25th and 75th percentiles).

What it does:

- Scales based on the middle bulk of your data, ignoring extremes

- Tails can do whatever they want without warping the transformation for typical values

- More stable when your data has legitimate outliers that you cannot remove

Best used for:

- Financial transactions, where most purchases are small, but occasional legitimate high-value transactions occur

- Income data, which tends to have long right tails

- Sensor readings where spikes represent real events

- Any very skewed distribution and situation where mean-based approaches get dragged around by extreme values

Why it helps with skewed data:

Income distributions are a good example. Most people earn moderate amounts, and some earn enormous amounts: a classic right-skewed distribution. Standard deviation gets inflated by the high earners, which makes standardization less useful for the majority of observations. Median and IQR stay anchored to the middle of the distribution regardless.

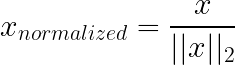

Unit-norm vector normalization

Unit-norm (L1/L2) normalization operates differently from the techniques above: instead of scaling features (columns), it commonly scales individual samples (rows). Each sample vector gets rescaled, so its length is 1 under a chosen norm (often L2), which removes overall magnitude and keeps only direction/proportions.

Don’t confuse this with L1/L2 regularization (Lasso/Ridge): regularization modifies the training objective by adding a penalty on model weights to reduce overfitting, not by rescaling input vectors.

How it works: In L2 normalization, each row gets divided by its Euclidean norm, so squared values sum to one. L1 uses the sum of absolute values instead.

What it does:

- Removes magnitude from the equation

- Makes rows comparable by proportion rather than raw size

- Angle between vectors becomes the signal; how long the vector is becomes irrelevant

Best used for:

- Text data represented as word count vectors: a 50,000-word report naturally has bigger counts than a 500-word email, but L2 lets you compare content proportions

- Anything involving cosine similarity

- Document classification, information retrieval, and recommendation systems based on content

Not useful for:

Situations where magnitude actually matters. If the total word count is meaningful for your task, normalizing it away loses information.

Database normalization

Database normalization refers to restructuring relational tables to eliminate redundancy and improve data integrity—for example, ensuring a customer's email is stored in exactly one place rather than repeated in every order record.

It has no connection to feature scaling.

The term simply overlaps. In machine learning, "normalization" almost always refers to scaling numeric values. In data engineering or SQL, it refers to organizing table structures (often discussed as 1NF, 2NF, or 3NF).

Key Distinction:

- Feature normalization (ML): Transforming numbers (e.g., 0–1 scaling) to help models learn.

- Database normalization (SQL): Organizing schema to prevent data duplication.

If a data engineer asks you to "normalize the database," they want you to fix the table structure, not run MinMaxScaler.

For a deeper dive, check out this guide on database normalization in SQL.

How to Normalize Data in Practice

Implementing normalization correctly requires attention to the order of operations, particularly around train/test splits. The code itself is straightforward, but subtle mistakes in sequencing can invalidate your entire evaluation.

Normalizing data in Python

Scikit-learn gives you the scalers, but the main rule is procedural, not mathematical: split first, fit on train only, then reuse that fitted transformer everywhere else.

Why the fuss? Because scaling learns numbers from data: min/max, mean/std, median/IQR. If those numbers are computed using the test set, you have quietly let future information leak into training. Nothing crashes, but your metrics just stop meaning what you think they mean.

A minimal example:

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.preprocessing import MinMaxScaler, StandardScaler, RobustScaler

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Example data

data = pd.DataFrame({

'age': [25, 32, 47, 51, 62, 28, 35, 44],

'income': [30000, 45000, 72000, 85000, 120000, 38000, 55000, 67000],

'score': [0.2, 0.5, 0.7, 0.4, 0.9, 0.3, 0.6, 0.8]

})

# Split happens before any scaling

train_data, test_data = train_test_split(data, test_size=0.25, random_state=42)At this point, you treat the training split as “what the world looked like when I built the model.” The test split is “new, unseen data.” Your scaler needs to learn the world from the first one only.

MinMaxScaler

Min-max standardization is straightforward: it stores the training minimum and maximum for each column, then applies the same mapping later.

scaler = MinMaxScaler()

scaler.fit(train_data) # training only

train_scaled = scaler.transform(train_data)

test_scaled = scaler.transform(test_data)If you ever see yourself calling fit() on the test set, pause. That defeats the point of holding out a test set in the first place.

StandardScaler

StandardScaler stores mean and standard deviation from the training split, then uses those same values to transform both train and test.

scaler = StandardScaler()

scaler.fit(train_data)

train_standardized = scaler.transform(train_data)

test_standardized = scaler.transform(test_data)This is the one that quietly breaks when leakage happens, because the mean/std are easy to “stabilize” by accidentally using more data than you should.

RobustScaler

RobustScaler does the same “fit once, reuse forever” routine, but uses median and IQR, so a few extreme points do not dictate the scale.

scaler = RobustScaler()

scaler.fit(train_data)

train_robust = scaler.transform(train_data)

test_robust = scaler.transform(test_data)A practical tell that robust scaling is worth it: you have a long tail you actually want to keep (payments, claims, sensor spikes), and you do not want one weird day to squeeze the rest of the feature into near-zero.

Quick pandas calculations

For quick exploratory work, doing the math directly in pandas is fine, as long as you are honest about what you are doing: this is for eyeballing distributions, not for model evaluation.

# Min-max

df_minmax = (data - data.min()) / (data.max() - data.min())

# Z-score

df_zscore = (data - data.mean()) / data.std()Preventing data leakage

Danger here: statistics are based on the entire dataset. Do this before splitting, and test values influence the transformation. Your evaluation loses meaning because preprocessing already peeked at answers it should not have seen.

The leakage pattern usually looks like this:

Doing it the wrong way:

scaler = MinMaxScaler()

scaled_all = scaler.fit_transform(full_data) # problem

train, test = split(scaled_all)This approach normalizes the data before splitting, so the test data has already influenced the transformation.

Doing it the right way:

By splitting the data first, we ensure the scaler learns statistics solely from the training set, keeping the test data truly unseen.

scaler = MinMaxScaler()

scaler.fit(train_data)

train_scaled = scaler.transform(train_data)

test_scaled = scaler.transform(test_data)Same operations, different order. And the order is the whole point.

If you’d rather practice preprocessing end-to-end (including standardizing correctly and avoiding leakage), this course is built for that: Preprocessing for Machine Learning in Python.

Normalization in SQL

As we mentioned before, we have different meanings of the same word. Here, “normalization” is not a numeric transformation. It is a structural decision to stop duplicating facts.

If your orders table stores customer_email on every row, the database will let you do it. The database will also happily accept contradictions later: one email in one row, a different email in another, and no obvious way to know which one is “real.”

Before normalization:

CREATE TABLE orders_denormalized (

order_id INT,

customer_name VARCHAR(100),

customer_email VARCHAR(100),

product_name VARCHAR(100),

product_price DECIMAL(10,2),

quantity INT

);Customer details are repeated in every row. Updating email means finding and modifying all their orders.

After normalization:

CREATE TABLE customers (

customer_id INT PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(100),

email VARCHAR(100)

);

CREATE TABLE products (

product_id INT PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(100),

price DECIMAL(10,2)

);

CREATE TABLE orders (

order_id INT PRIMARY KEY,

customer_id INT REFERENCES customers(customer_id),

product_id INT REFERENCES products(product_id),

quantity INT

);Customer info exists once. Queries need joins, but updates happen in one spot.

How to Choose the Right Normalization Technique

Finally, I want to give you a decision framework for the next time you wonder which normalization technique to use.

Min-max when bounds exist

Min-max scaling works best when your data has known, stable bounds that will not change between training and deployment. Pixel values always fall between 0 and 255. Probability scores cannot exceed 1. Exam grades have defined minimums and maximums.

This approach also fits when your model specifically expects bounded input, as some neural network architectures do. However, avoid min-max scaling when outliers are present, since a single extreme value can compress all normal observations into a narrow range near zero.

Standardization as a fallback

Standardization serves as a reasonable default when you lack strong assumptions about your data's bounds or distribution. It works well for features with varying ranges, unknown limits, or roughly bell-shaped distributions.

Many algorithm implementations assume or recommend standardized input, including most neural network frameworks and logistic regression libraries. If you are unsure which approach to use and your data does not have obvious natural bounds, standardization is usually a safe choice.

Robust for real-world messiness

Robust scaling becomes the right choice when your data contains significant outliers that represent legitimate values rather than errors. Financial transaction data typically has this characteristic: most purchases are small, but occasional large charges are real and should remain in the dataset.

Income distributions, sensor readings with occasional spikes, and any data with heavy skew or long tails benefit from robust scaling. The median and interquartile range stay anchored to the bulk of your distribution regardless of what happens in the extremes.

When not to normalize

Tree-based models like random forests, XGBoost, and gradient boosted trees split on threshold values and never compute distances or gradients across features. Scale is invisible to them, so normalization adds complexity without benefit.

One-hot encoded features are already binary (0s and 1s), so scaling them accomplishes nothing useful. Categorical-only datasets fall into the same category.

Sometimes, domain-specific transformations work better than generic normalization:

- Log scaling compresses long right tails while spreading out bunched-up lower values, which often works better for income or price data than standard approaches.

- Binning makes sense when category membership matters more than precise numeric values.

- Power transforms help stabilize variance in specific situations.

Summary comparison table

Here’s an overview of the techniques and their use cases:

|

Technique |

Use When |

Avoid When |

Output Range |

|

Min-max |

Data has known bounds; model expects bounded input |

Outliers present; bounds may shift |

0 to 1 (fixed) |

|

Standardization |

Unknown bounds; roughly normal distribution; unsure which to use |

Need guaranteed bounds; heavy outliers |

Unbounded |

|

Robust scaling |

Significant outliers; skewed distributions; long tails |

Data is already clean and symmetric |

Unbounded |

|

L1/L2 normalization |

Text data; cosine similarity; high-dimensional spaces |

Magnitude carries meaning |

Unit vector |

|

None |

Tree-based models; one-hot features; domain-specific transforms available |

Gradient or distance-based models |

Original |

Conclusion

Scale differences cause real trouble for models that care about them. Distance metrics favor large-magnitude features. Gradient descent struggles when gradients span orders of magnitude. Training stalls or explodes for reasons that are not obvious from looking at the code or architecture.

Normalization addresses this. Use min-max normalization for bounded data, robust scaling when outliers are real and cannot be removed, and standardization as a reasonable default. Mechanics are straightforward: fit in training, apply everywhere consistently.

In my experience, what costs time is not recognizing when scaling matters, then debugging model behavior for days when preprocessing was the answer. Or the opposite mistake, such as applying scaling reflexively to models that do not care, adding complexity without benefit.

Ready to level up? Our comprehensive Machine Learning Engineer track teaches you everything you need to know about the machine learning workflow.

Data Normalization FAQs

What is the difference between normalization and standardization?

While the terms are often used interchangeably in documentation, they refer to distinct techniques. Normalization (specifically Min-Max scaling) typically involves rescaling data to a fixed range, usually 0 - 1. Standardization (Z-score normalization) transforms data so that it has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

Does every machine learning model require data scaling?

No. Algorithms that rely on distance calculations (like K-Nearest Neighbors) or gradient descent (like Neural Networks) require scaling to function correctly. However, tree-based models, such as Random Forests and XGBoost, process features individually based on splitting rules and are generally invariant to feature scaling.

At what stage in the pipeline should I fit the scaler?

You must fit the scaler on the training data only, specifically after the train-test split. If you fit the scaler on the entire dataset before splitting, information from the test set influences the training process, resulting in misleading evaluation metrics.

What are the consequences of skipping normalization?

The impact varies by algorithm. Neural Networks may struggle to converge, leading to erratic training or complete failure to learn. K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) will yield biased results because the algorithm will weigh features with larger magnitudes (e.g., salary) much more heavily than features with smaller magnitudes (e.g., age).

Are there scenarios where scaling can backfire?

Yes. If your dataset contains significant outliers, Min-Max normalization can compress the majority of the "normal" data into a very small range and effectively suppress all useful variance. Additionally, scaling is generally unnecessary for categorical features that have been one-hot encoded, as they are already binary (0 and 1).

Josep is a freelance Data Scientist specializing in European projects, with expertise in data storage, processing, advanced analytics, and impactful data storytelling.

As an educator, he teaches Big Data in the Master’s program at the University of Navarra and shares insights through articles on platforms like Medium, KDNuggets, and DataCamp. Josep also writes about Data and Tech in his newsletter Databites (databites.tech).

He holds a BS in Engineering Physics from the Polytechnic University of Catalonia and an MS in Intelligent Interactive Systems from Pompeu Fabra University.