Course

Rumors of Anthropic’s next release have been rumbling around for the last few days. While many expected Claude Sonnet 5, the first release of the year comes in the form of Claude Opus 4.6.

With a 1 million-token context window, adaptive thinking, conversation compaction, and a range of chart-topping benchmarks, Claude Opus 4.6 is an improvement on Opus 4.5. As Anthropic terms it, they have upgraded their smartest model. Alongside the model, Anthropic also launched agent teams in Claude Code and Claude in PowerPoint.

In this article, we’ll cover everything that’s new with Claude Opus 4.6, looking at the new features, exploring the benchmarks, and putting it through its paces with several hands-on examples.

To learn more about some of the latest Claude features, I recommend checking out our guides to Claude Cowork and Claude Code, as well as our OpenClaw tutorial.

What Is Claude Opus 4.6?

Claude Opus 4.6 is the latest large language model from Anthropic. Following on from Opus 4.5, it represents a significant upgrade to the company’s ‘smartest’ model tier.

From the release blog, Anthropic claims it has a greater focus on agentic coding, deep reasoning, and self-correction. This means that there is a shift from action to sustained action.

Opus 4.6 is designed to plan more carefully, has improved coherence over longer periods, and identifies errors in its own workings. All this means that Claude Opus 4.6 tops several benchmarks, including the top score on the Terminal-Bench 2.0 coding evaluation and beating all other frontier models on Humanity’s Last Exam.

One of the things that stands out the most to me is the improved context window in Claude Opus 4.6. With 1 million tokens in the beta, this brings the new model in line with Gemini 3, meaning it can process more info without losing sight of context.

What’s New With Claude Opus 4.6?

There are several notable new features in Claude Opus 4.6, many of which are focused on agentic workflows. Let’s take a look at some of the key points:

Agent teams

Agent teams are an improvement on the ‘subagents’ we saw in previous versions of Claude. Agent teams allow you to spin up multiple, fully independent Claude instances that can work in parallel. One session is the ‘lead’ agent that coordinates things, while ‘teammates’ handle the actual execution.

What I find most interesting is that each team member has its own context window, allowing for more thorough execution. Each teammate can also communicate with others in the team directly.

Of course, this feature comes with a potential downside - the cost. As each agent has its own context window, you can soon start to burn through your tokens. As such, Anthropic recommends that you use these for scenarios when there are higher levels of complexity.

Conversation compaction

One neat feature of Claude Opus 4.6 is the context compaction. This quality-of-life upgrade helps avoid issues when you’re running long workflows that max out context windows. Typically, you’d hit a context wall where performance starts to degrade.

With conversation compaction, Claude Opus 4.6 can automatically detect when a conversation is reaching a token threshold and summarize the existing conversation into a concise block (a compaction block).

This feature should help to preserve the essentials of your interactions while also freeing up space to continue your work. If you’re planning on using task-oriented agents that need to run for a long time, this could keep them on track with a much-improved memory.

Adaptive thinking and effort

There are two features of Claude Opus 4.6 that determine whether it needs to use extended thinking and how hard it tries with that thinking.

Adaptive thinking allows the model to determine how complex your prompt is. Based on the simplicity or complexity, it will decide whether to use extended thinking. Rather than having a manual setting for how many tokes in uses for this, Claude will adjust its budget based on the complexity of each request.

The effort parameter allows you to set how eager or conservative Claude is about spending tokens. Essentially, it means you can balance token efficiency and how thorough responses are.

When using Claude Opus 4.6 in the API, you can set these parameters manually. For example:

- Max effort: Claude always uses extended thinking, and there are no constraints on depth.

- High effort: With this default setting, Claude always thinks and provides deep reasoning.

- Medium effort: This activates moderate thinking, and it may skip thinking for the simplest queries.

- Low effort: Claude skips thinking for simple tasks and minimizes thinking in favor of speed.

Claude in PowerPoint

We recently covered Claude in Excel, showing how the add-on can help you with various tasks in a side-panel of your Excel spreadsheet. As well as improving the functionality of this tool, Anthropic announced Claude in PowerPoint.

This integration respects your slide masters, fonts, and layouts. You can feed it a corporate template and ask it to build a specific section, or select a slide and ask it to convert dense text into a native, editable diagram.

The emphasis on generating editable PowerPoint objects rather than just "pictures of slides" makes this a genuine productivity tool rather than just a concept generator.

Claude in PowerPoint is currently in research preview for Max and Enterprise users.

Testing Claude Opus 4.6: Hands-On Examples

Many of Opus 4.6's headline claims center on harder coding tasks and deeper reasoning. These skills all rest on a certain foundation: the ability to hold multiple constraints in mind, reason across many steps, and catch mistakes.

With this in mind, we put Opus 4.6 through a series of multi-step logic, math, and coding challenges. We wanted to see if we could expose some known and common LLM weaknesses – things like cascading calculation errors, spatial reasoning (always an issue), and questions that involve constraints. We also included a specific debugging task because Anthropic’s announcement bragged about how good Opus 4.6 was with root cause analysis and other debugging issues.

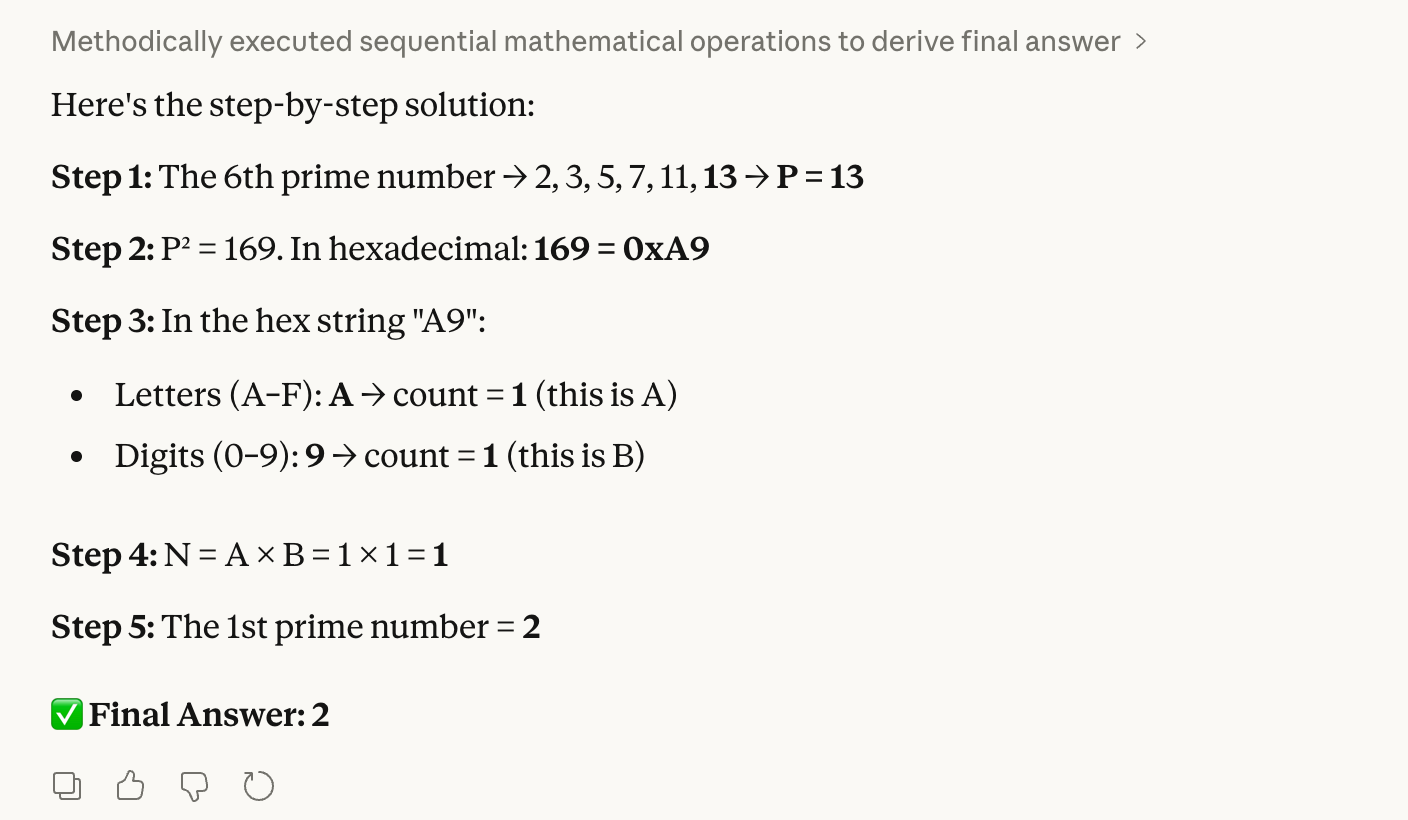

Test 1: Hex-to-decimal logic

Our first test combines prime numbers, hexadecimals, and counting:

Step 1: Find the 6th prime number. Let this be P.

Step 2: Convert the square of P into hexadecimal.

Step 3: Count the letters (A–F) and digits (0–9) in that hex string. Let these be A and B.

Step 4: Multiply A × B. Let this be N.

Step 5: Find the Nth prime number.It sounds a bit complex, but this test is pretty easy for us humans to verify. The correct answer we know is 2 because the 6th prime is 13; 13 squared is 169, which is "A9" in hex. This has 1 letter × 1 digit, which equals 1 when we multiply them, and the first prime is 2.

The worry is that a model could trip up with hex conversion, which would cascade into a completely wrong final answer. As you can see, Opus 4.6 had no trouble:

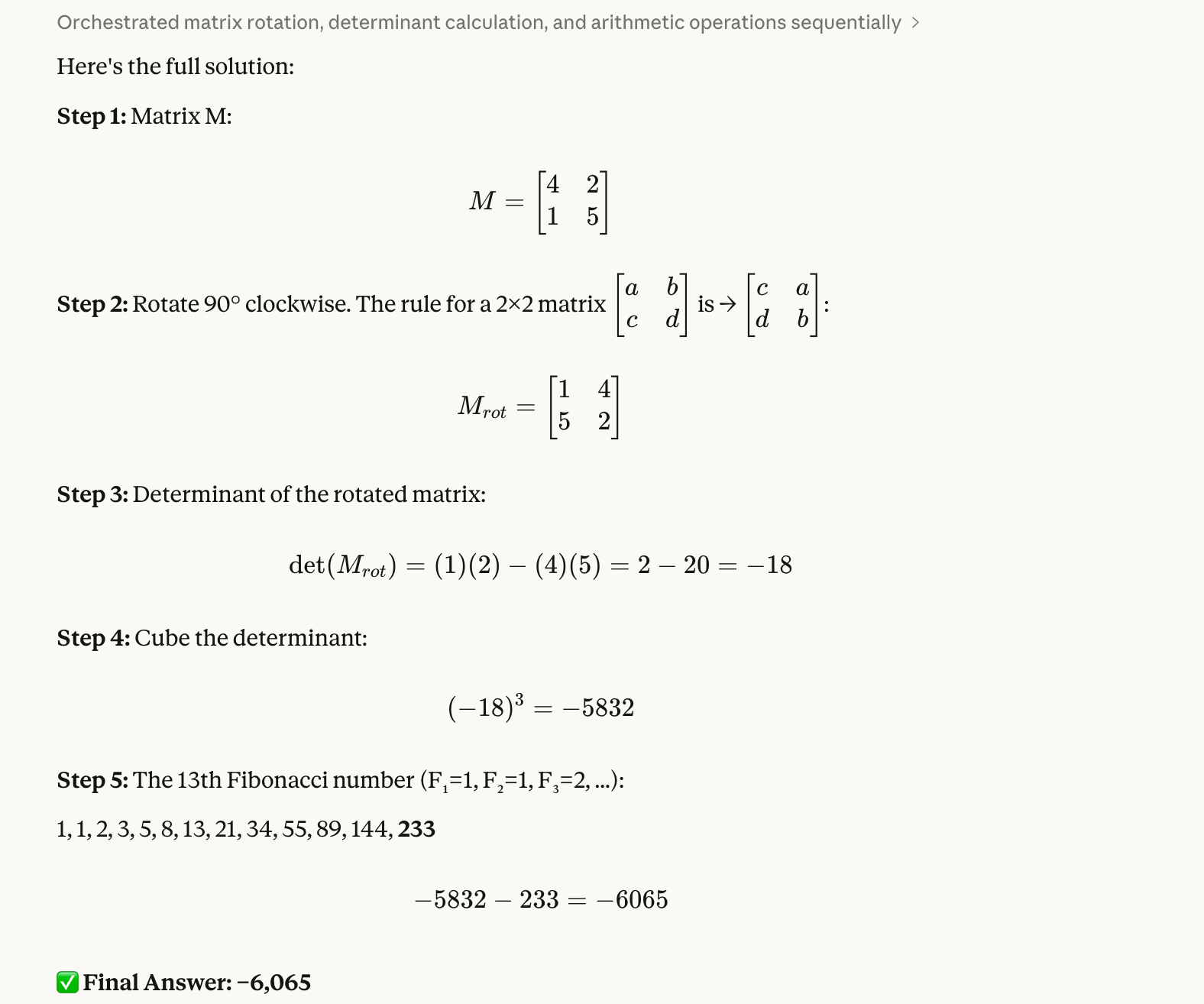

Test 2: Rotating a matrix

Our second test is a test of spatial reasoning and negative number handling:

Step 1: Create a 2×2 matrix M with top row [4, 2] and bottom row [1, 5].

Step 2: Rotate M 90 degrees clockwise.

Step 3: Calculate the determinant of the rotated matrix.

Step 4: Cube that determinant.

Step 5: Subtract the 13th Fibonacci number from the result.This one took a little more work to verify on our end. The correct answer is -6,065. We know this because the rotated matrix is [[1, 4], [5, 2]]; we can then use Python to find the determinant, which is -18 and when we cube this number, we get -5,832; finally, we subtract 233 and get -6,065.

We had liked the idea of this test because we know from experience that models often swap matrix elements incorrectly or else they lose the negative sign partway through. Again, Opus 4.6 had no trouble:

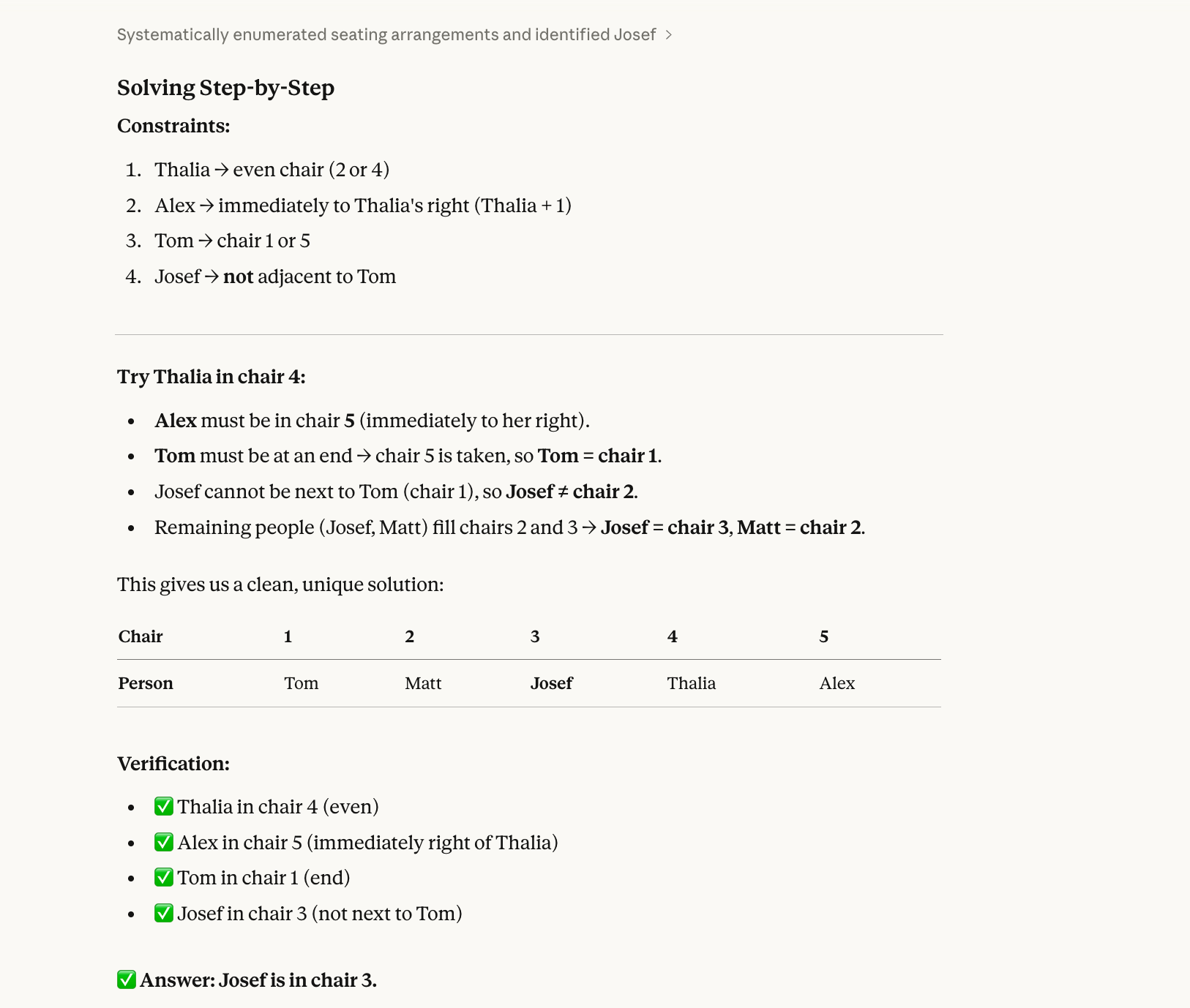

Test 3: A seating arrangement quiz

For our third test, we tried a constraint satisfaction problem that requires backtracking:

Five people (Alex, Josef, Matt, Thalia, Tom) sit in chairs 1–5.

Thalia is in an even-numbered chair.Alex is immediately to Thalia’s right.Tom is at one end.Josef is not next to Tom.Who is in chair 3?The correct answer to this test is Josef. (Alex-1, Matt-2, Josef-3, Thalia-4, Tom-5.) You can work this one out on a piece of paper with some effort.

The basic reason a model might get this kind of question wrong is because models have historically solved sequentially, not holistically. They read "Thalia is in an even chair" and pick one (say, chair 2) without checking if that choice works with all the other constraints. Then they commit to it, fill in more chairs, and eventually hit a conflict, but by then they've written themselves into a corner and don't go back to try Thalia in chair 4 instead.

Opus 4.6 got this one right, also:

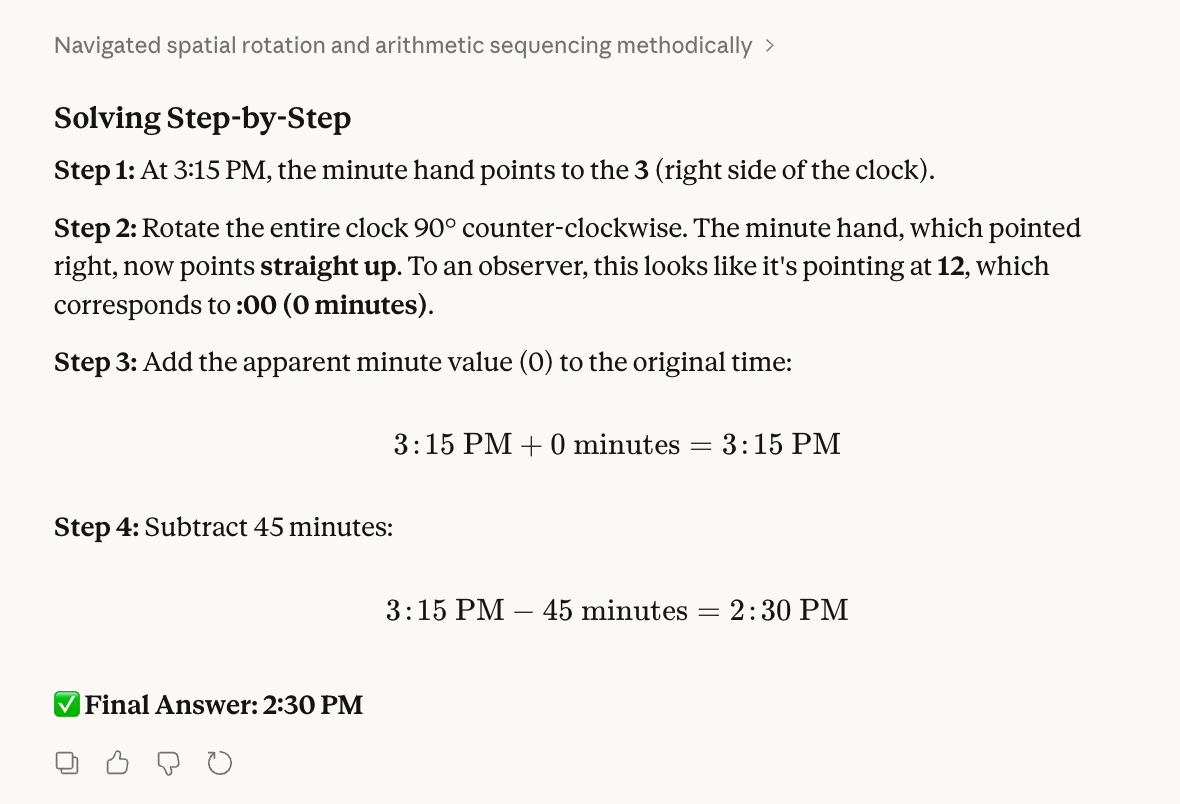

Test 4: A clock puzzle

Our fourth test evaluates spatial visualization and physical intuition:

Step 1: Imagine a clock currently showing 3:15 PM.

Step 2: Rotate the clock 90 degrees counter-clockwise (physically turning the whole clock face). After the rotation, what time does the minute hand appear to be pointing at?

Step 3: Take that new "apparent" minute value and add it to the original time (3:15 PM).

Step 4: Subtract 45 minutes from that result.

Step 5: What is the final time?To verify this one, I actually took the watch off my wrist and spun it around.

The correct answer is 2:30 PM. At 3:15, the minute hand points at the "3". When I pointed the 12 at the window on my left, the "3" moved to where the "12" was. I then added 0 to 3:15, subtracted 45 minutes, and I got 2:30 PM.

In designing the test, we expected that models might confuse rotating the clock face with moving the hand. We have also heard that models tend to think of adding 0 as suspicious and, therefore, will try to force a different number.

However, Opus 4.6 managed to solve this problem; it got the right answer, also:

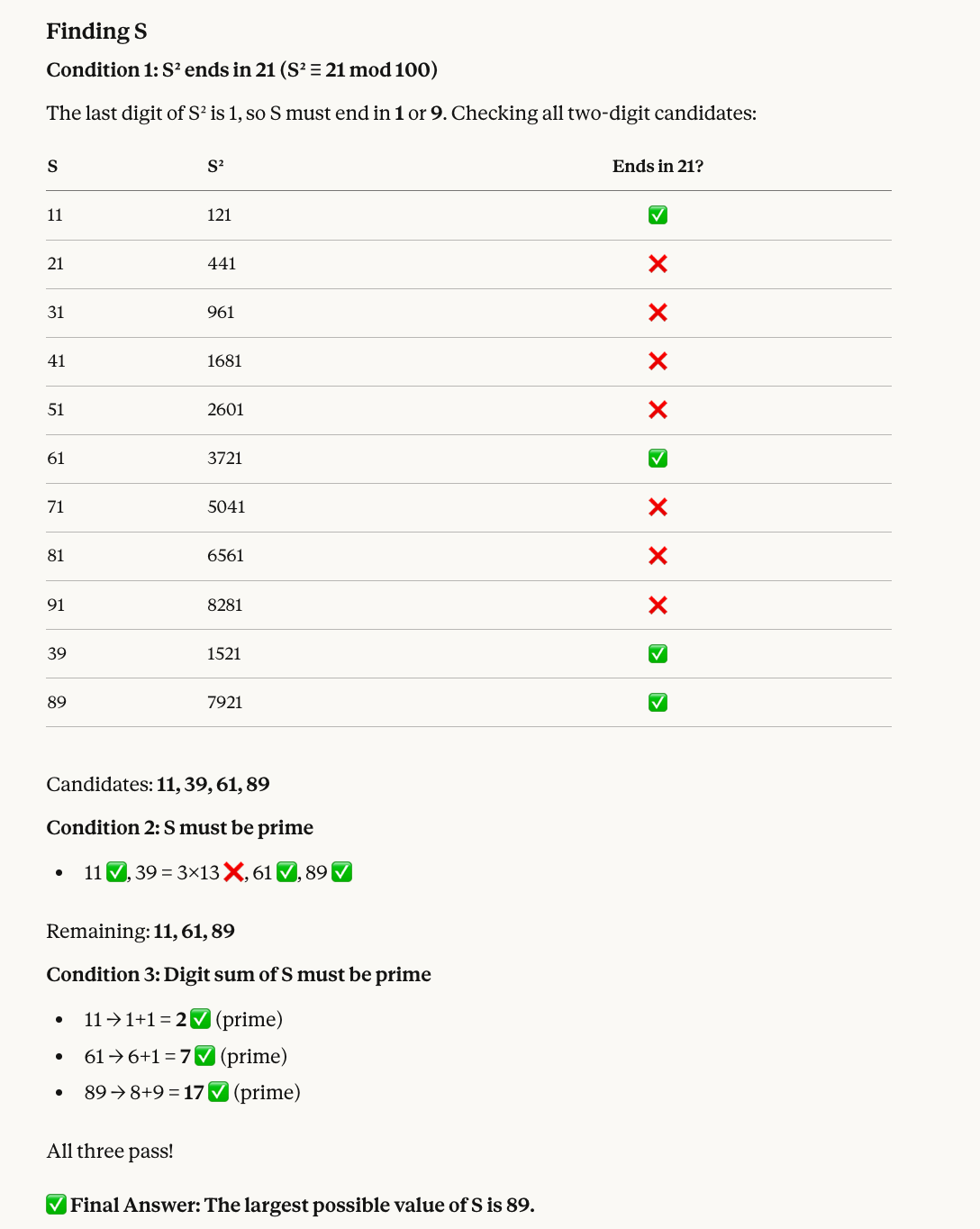

Test 5: A number theory puzzle

Our fifth test combines modular arithmetic with prime filtering:

Find a two-digit number S that satisfies all of the following:

* When S is squared, the last two digits of the result are 21.

* S must be a prime number.

* The sum of the digits of S must also be a prime number.

What is the largest possible value of S?Here's why the correct number is 89: Numbers whose squares end in 21 include 11, 39, 61, and 89. Of these, 39 isn't prime, so we're left with 11, 61, and 89. All three have digit sums that are prime (2, 7, and 17, respectively), so the largest is 89.

Opus 4.6 got the right answer yet again, and this time it also included a helpful visual:

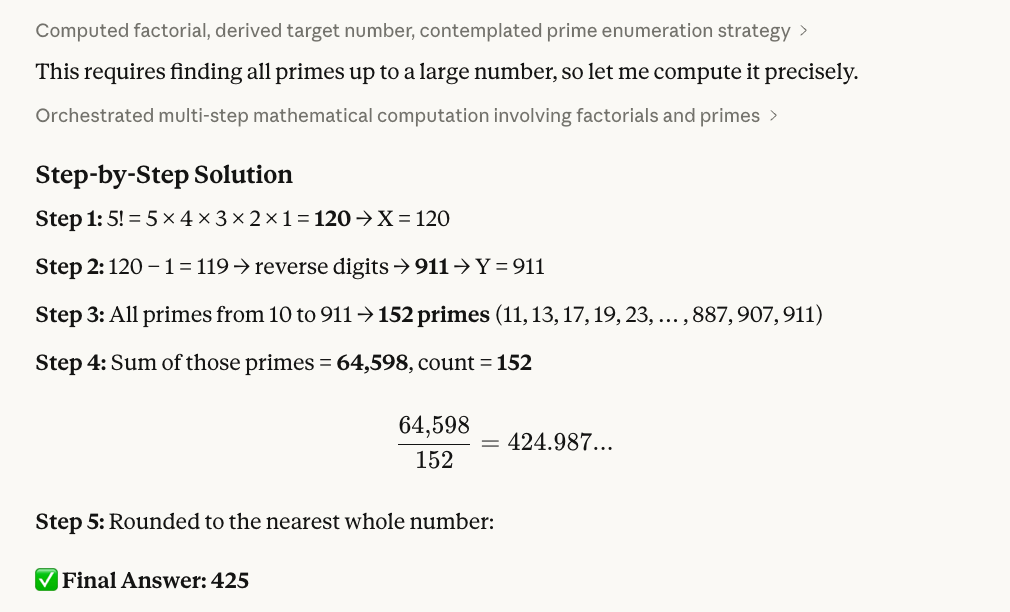

Test 6: Reversing digits

The next test chains together factorial math, string manipulation, and primes:

Step 1: Calculate 5! (5 factorial). Let this result be X.

Step 2: Take X, subtract 1, and reverse the digits of the result. Let this new number be Y.

Step 3: Identify all prime numbers (p) such that 10 ≤ p ≤ Y.

Step 4: Calculate the sum of these primes and divide it by the total count of primes found in that range.

Step 5: Provide the final average, rounded to the nearest whole number.Here's how we verified 425 as the correct answer: 5! = 120; subtract 1 to get 119; reverse the digits to get 911. Then, using some R code (shown below), we could see that there are 152 primes between 10 and 911, and their sum is 64,598. Finally, using R again, we divide and round: 64,598 ÷ 152 ≈ 425.

Here is the R script we used:

# Step 1: Calculate 5!

X <- factorial(5)

cat("Step 1: X =", X, "\n")

# Step 2: Subtract 1 and reverse digits

result <- X - 1

Y <- as.numeric(paste0(rev(strsplit(as.character(result), "")[[1]]), collapse = ""))

cat("Step 2:", X, "- 1 =", result, "-> reversed ->", Y, "\n")

# Step 3: Find all primes between 10 and Y

is_prime <- function(n) {

if (n < 2) return(FALSE)

if (n == 2) return(TRUE)

if (n %% 2 == 0) return(FALSE)

for (i in 3:floor(sqrt(n))) {

if (n %% i == 0) return(FALSE)

}

return(TRUE)

}

primes <- Filter(is_prime, 10:Y)

cat("Step 3: Found", length(primes), "primes between 10 and", Y, "\n")

# Step 4: Sum and average

total <- sum(primes)

count <- length(primes)

avg <- total / count

cat("Step 4: Sum =", total, ", Count =", count, ", Average =", avg, "\n")

# Step 5: Round

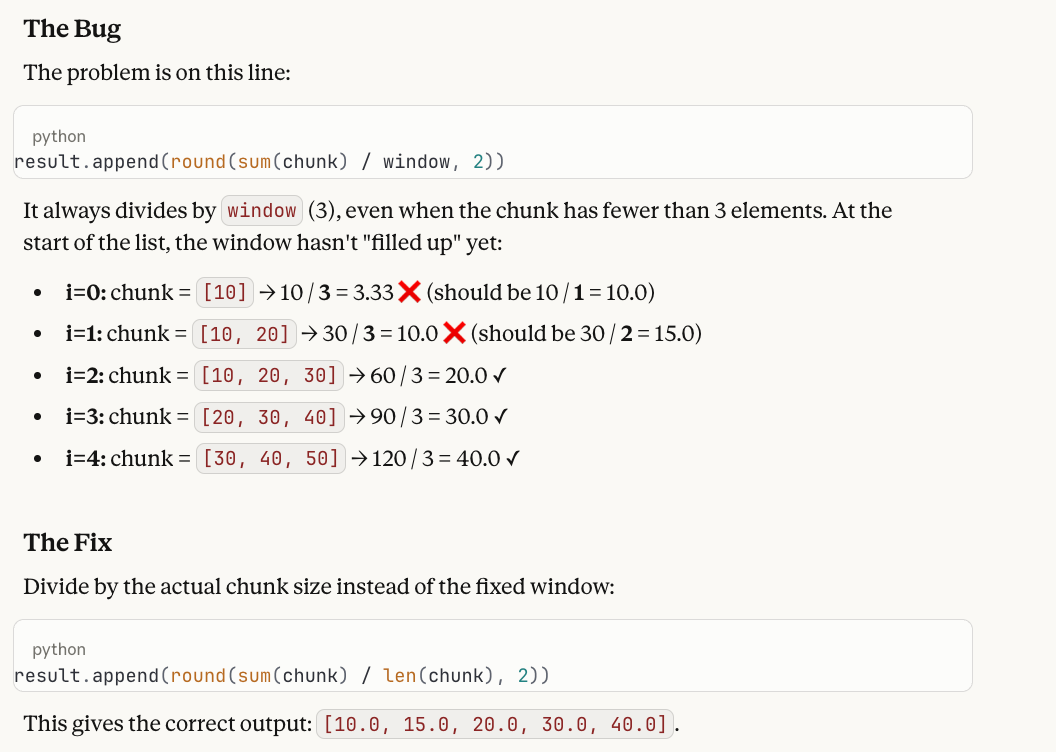

cat("Step 5: Rounded =", round(avg), "\n")Test 7: Code debugging

Our next test targets one of Opus 4.6's major claims: diagnosing bugs in code. We know that models often trace through code correctly line-by-line but fail to connect the trace back to the underlying flaw.

A developer wrote this Python function to compute a running average:

def running_average(data, window=3):

result = []

for i in range(len(data)):

start = max(0, i - window + 1)

chunk = data[start:i + 1]

result.append(round(sum(chunk) / window, 2))

return result

When called with running_average([10, 20, 30, 40, 50]), the first two values in the output seem wrong. Why? Please help me fix what is wrong!Here's the answer and why it works as a test: the function always divides by window (3), even when the chunk has fewer than 3 elements at the start of the list. The buggy output is [3.33, 10.0, 20.0, 30.0, 40.0], but the first two values should be 10.0 and 15.0 since those chunks contain only 1 and 2 elements, respectively. The fix is changing / window to / len(chunk).

We like this test because models often trace through the loop perfectly, but then report "output looks correct" — they see the math happening step by step and don't flag that dividing a single element by 3 is wrong. It requires the model to hold intent (what a running average should do) alongside execution (what the code actually does) and spot the gap between them.

Test 8: A physics thought experiment

Our final test has no math, just counterfactual reasoning.

In a world where gravity repels objects instead of attracting them, what shape would rivers take?Granted, there's no single correct answer here, and it’s hard to imagine ourselves. But we're looking for the model to at least reason through the implications, and we think Claude Opus 4.6’s answer seems reasonable enough.

All in all, long story short, Opus 4.6 got a perfect score, although, as you saw, we did include one question where the answer was a little subjective, so you can be the final judge.

Claude Opus 4.6 Benchmarks

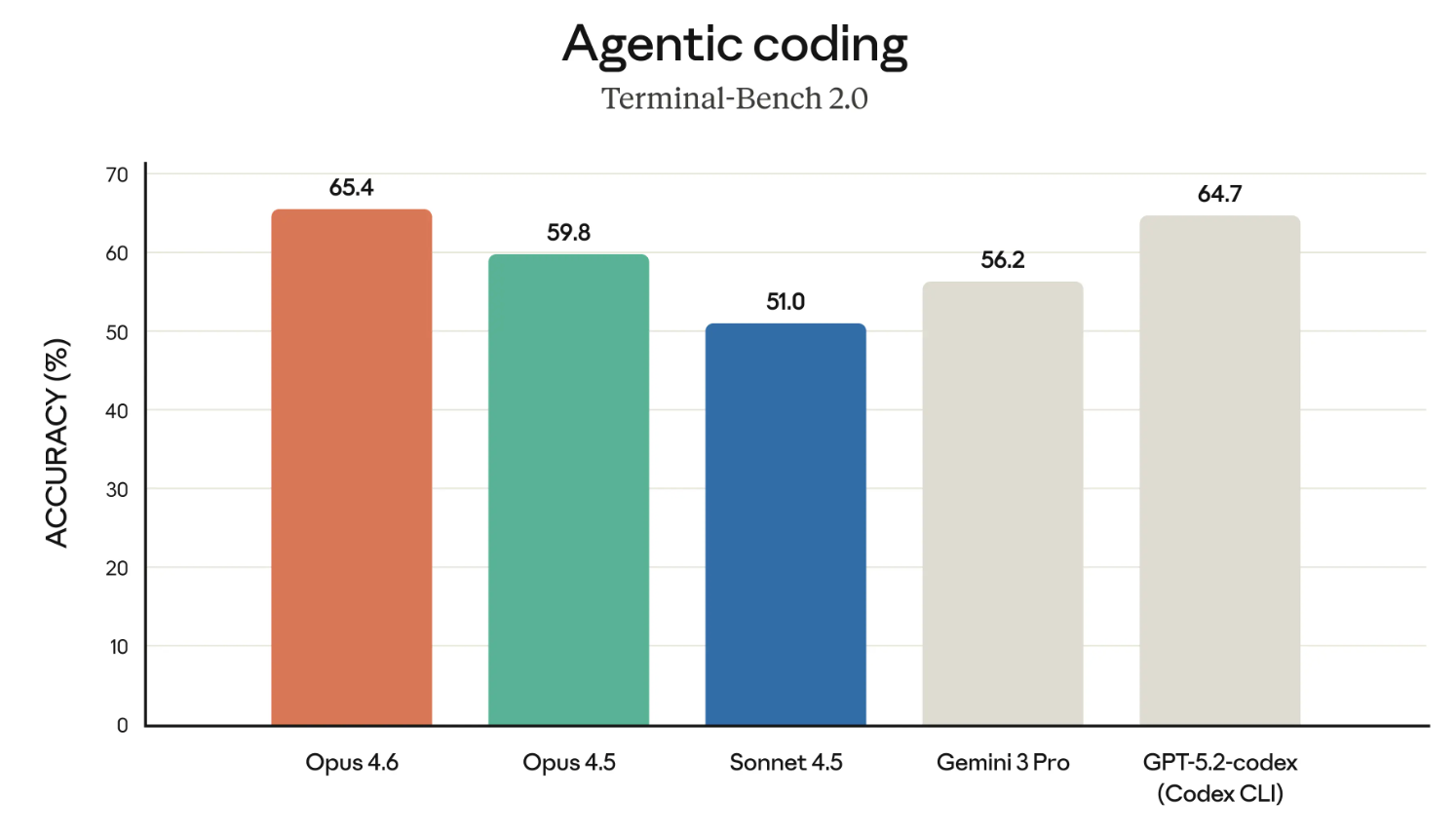

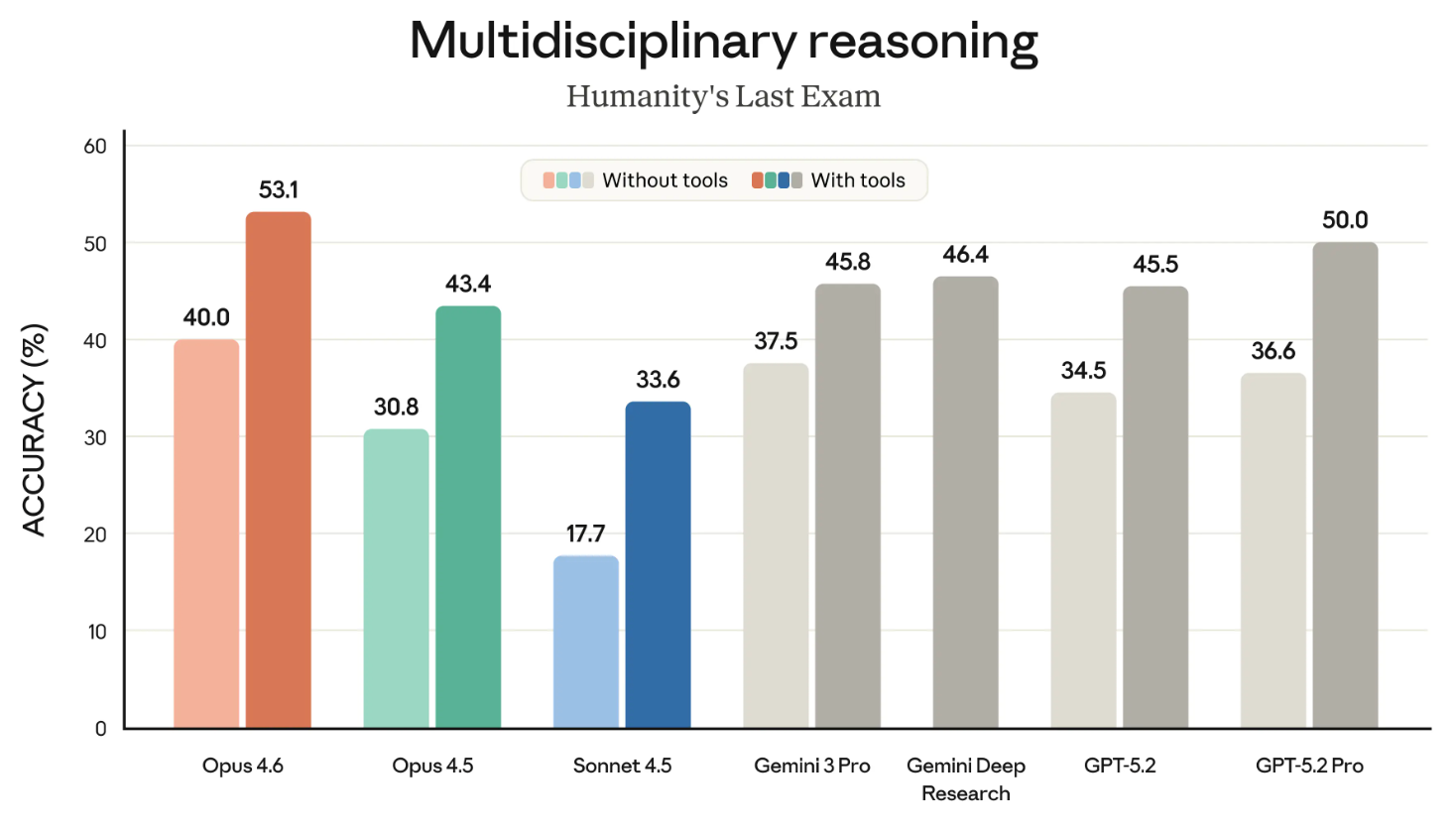

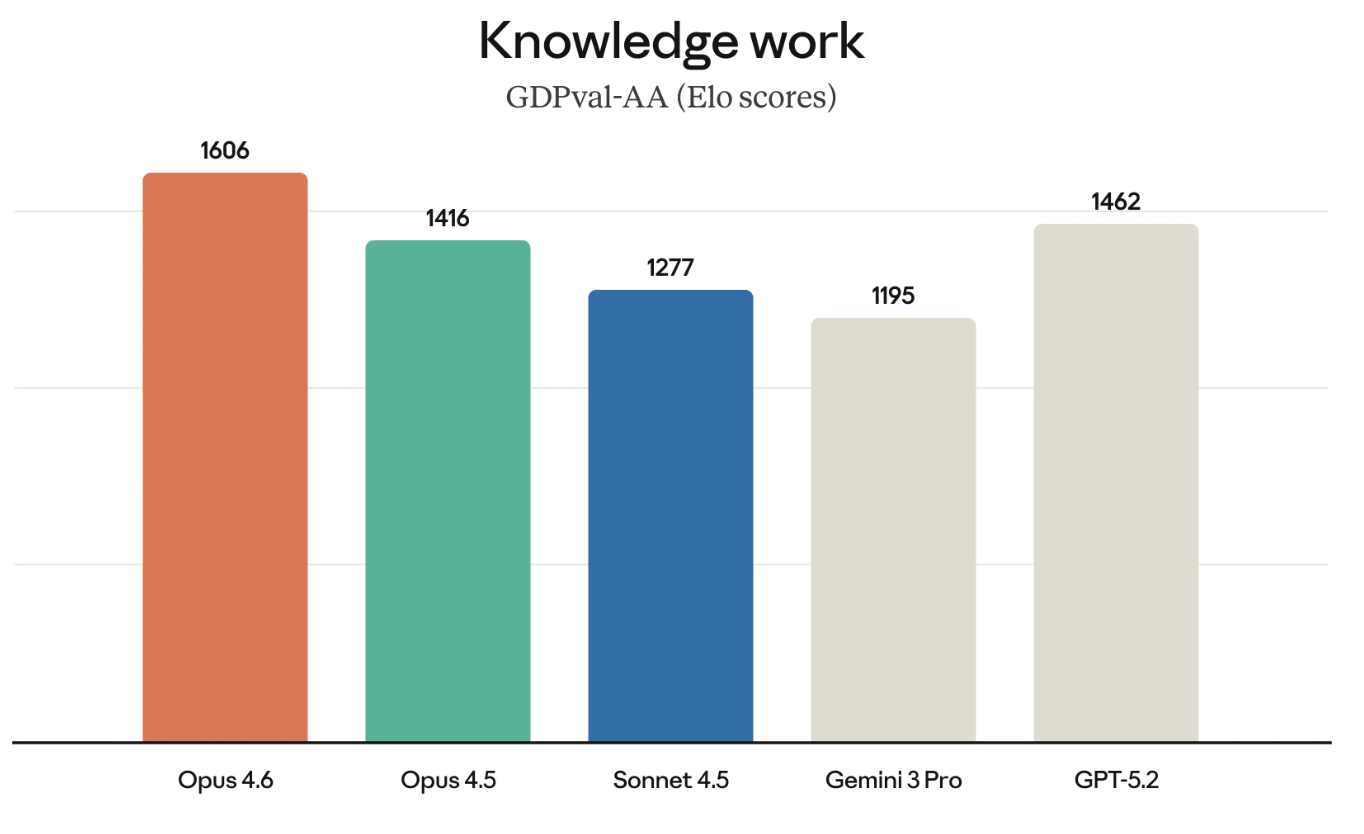

Opus 4.6 is the undisputed leader in at least four important benchmarks:

- Terminal-Bench 2.0

- Humanity’s Last Exam

- GDPval-AA

- BrowseComp

Terminal-Bench 2.0 is an agentic coding benchmark; Humanity’s Last Exam is a test of complex reasoning; GDPval-AA tests the performance of knowledge work; BrowseComp measures a model’s ability to find hard-to-find info online.

Terminal-Bench 2.0

The Claude models have a deserved reputation as one of the best coders. So let’s start by looking at the results of the Terminal-Bench 2.0 benchmark.

If the graph above seems to highlight Opus 4.6 in relation to GPT-5.2-codex – well, that’s surely intentional. Anthropic has been directly challenging OpenAI in several areas recently, and it’s making the case for enterprise use.

Humanity’s Last Exam

Humanity’s Last Exam is one of the most well-known benchmarks, and it’s one that all of us watch closely. It measures a model's ability to reason generally.

The following graph shows the success of the different frontier models on the HLE benchmark both with and without tools. (‘With tools’ means that the model was allowed to make use of external capabilities like searching the web and executing code.)

This graph might be better as two graphs. That minor point aside, the takeaway is clear: Opus 4.6 is the leader in both the ‘with tools’ and ‘without tools’ categories.

GDPval-AA

GDPval-AA (as the name suggests) is a test of what is deemed economically valuable knowledge work. Think about things like running financial models or doing research.

GDPval-AA and other, similar benchmarks are only becoming more important because they really measure the kinds of work that enterprises are actually paying for. The success of Opus 4.6 on GDPval-AA is also another direct challenge to the GPT suite of models because OpenAI and Anthropic are competing for a lot of the same customers.

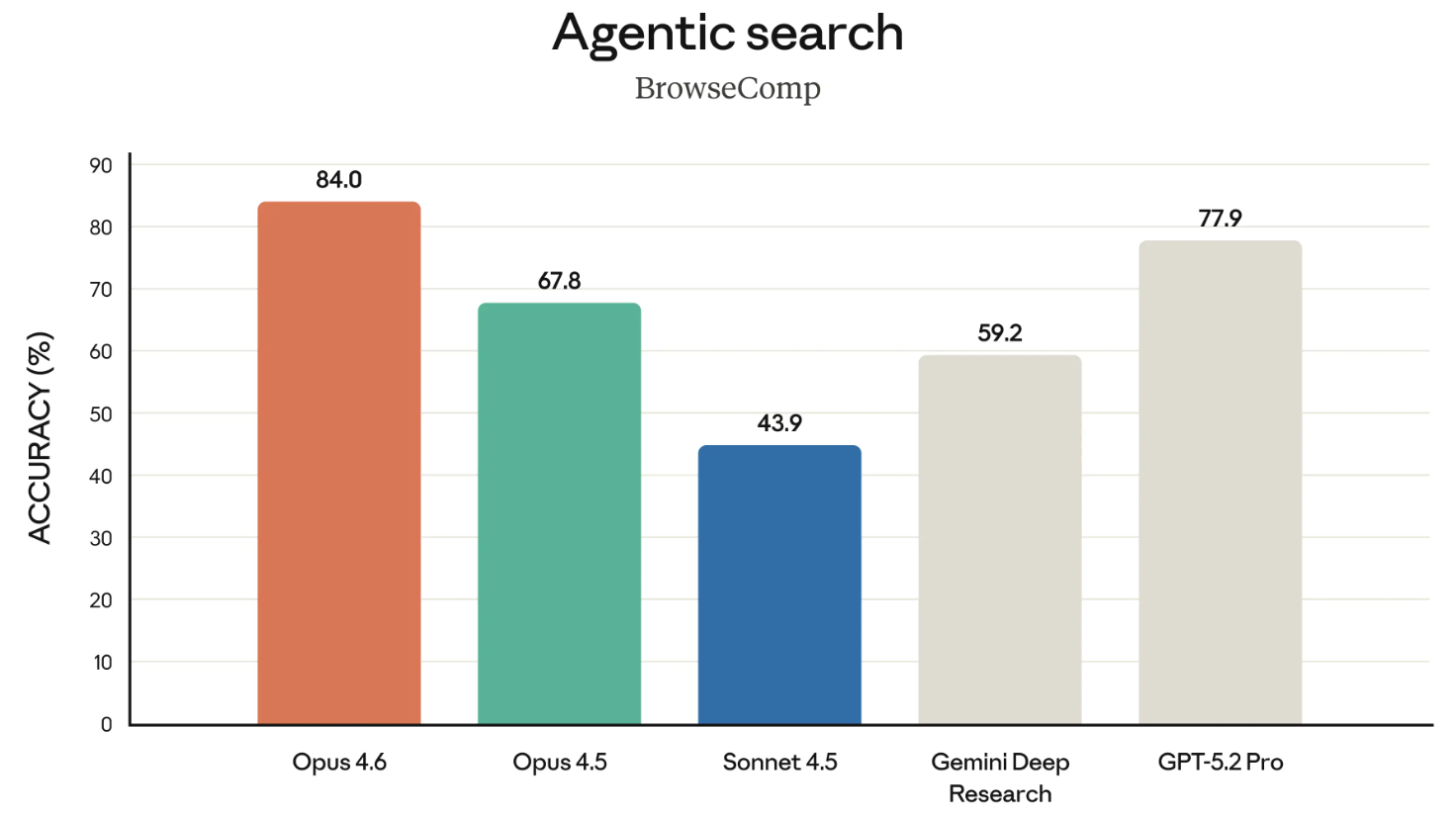

BrowseComp

BrowseComp is the final benchmark worth mentioning from the release. It measures a model's ability to track down hard-to-find info online. Some history: OpenAI actually developed BrowseComp to showcase the search capabilities of their own models.

In a pointed move, in this release, Anthropic directly linked to OpenAI's April 2025 announcement of the development of BrowseComp when highlighting that Opus 4.6 tops the charts on it. It was a bit of a shady move, citing OpenAI’s own benchmark back at them like that.

Claude 4.6 Pricing and Availability

Opus 4.6 is widely available at the time of this article. However, you can’t access Opus 4.6 without upgrading to a pro account, which comes with other benefits, like letting you use Claude in Excel.

If you’re a developer, you should use the claude-opus-4-6 in the Claude API. The pricing hasn’t changed: It’s still $5/$25 per million tokens. If you’re confused about the two numbers, know that the first number is what you pay to send tokens to the model (your prompts, I mean), and the second is what you pay for the tokens it generates back (the responses).

Final Thoughts

Claude Opus 4.6 tops the leaderboard on important benchmarks like GPDVal-AA, which measures how well a model performs on economically important tasks, which is what large enterprise customers care about. OpenAI might be rattled by this development because only hours ahead of the release of Opus 4.6, they announced OpenAI Frontier, which is a new enterprise platform for building, deploying, and managing AI agents in production.

In other words, rather than competing on model benchmarks, Frontier shows us that OpenAI is focused on the infrastructure around its suite of models, specifically by giving AI agents shared business context, permissions, and the ability to receive and learn from feedback over time. Losing ground on the benchmarks, OpenAI is signalling that its platform is better positioned to actually make agents useful in a company.

Whether that's a strategic pivot or a tacit admission that they're losing the model race is up to you to decide.

Overall, though, we’re impressed with what Anthropic has to offer with Claude Opus 4.6, and we’re looking forward to getting hands-on with the agent teams. If you’re keen to learn more about the Claude family, be sure to check out the Introduction to Claude Models course.

A senior editor in the AI and edtech space. Committed to exploring data and AI trends.

I'm a data science writer and editor with contributions to research articles in scientific journals. I'm especially interested in linear algebra, statistics, R, and the like. I also play a fair amount of chess!